ssa

by Stephen Von Slagle

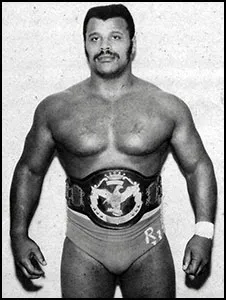

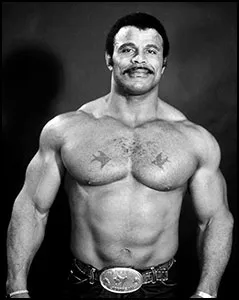

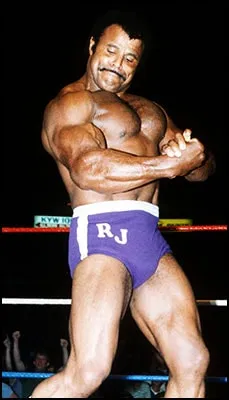

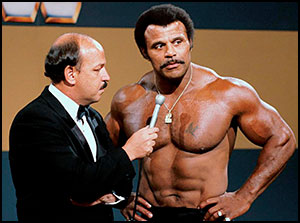

Rocky Johnson, the well-spoken, intelligent and athletic babyface from Nova Scotia, never allowed himself to be portrayed in a manner that he felt was demeaning, despite the stereotypical nature of professional wrestling that was so prevalent during his time in the business. Portrayed as a groundbreaking role model for people of all races, the talented Johnson blazed a trail which countless others (including his famous son) could use to follow. And, as one of the most well-travelled performers of his era, he also provided excitement and thrills for fans in virtually every corner of pro wrestling’s territorial globe.

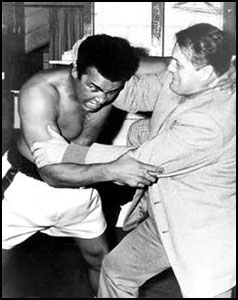

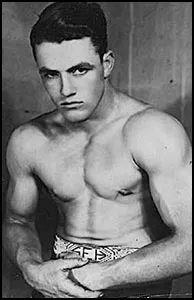

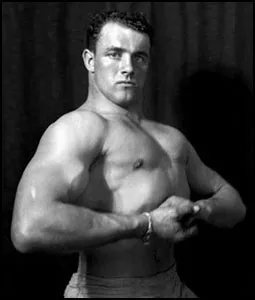

“The Soul Man” was born Wayde Douglas Bowles on August 24, 1944 in Amherst, Nova Scotia, the descendant of Black Loyalists who, following the American Revolutionary War, immigrated north to Canada. As a teenager, he moved to Toronto and it was there that Bowles discovered his love of combat sports, namely boxing and wrestling. Although he preferred wrestling, he excelled quicker as a boxer, and while he never turned pro, the talented Bowles was a sparring partner for champions such as Henry Clark, George Foreman and Muhammad Ali. Meanwhile, he continued to pursue his passion and in 1964 the muscular 6’2″ 250 lb. rookie made his pro wrestling debut under the name Drew Glasteau. After gaining some experience in eastern Canada, Bowles began competing as (and, later, legally changed his name to) Rocky Johnson, in honor of his two favorite boxers, Rocky Marciano and Jack Johnson.

“The Soul Man” was born Wayde Douglas Bowles on August 24, 1944 in Amherst, Nova Scotia, the descendant of Black Loyalists who, following the American Revolutionary War, immigrated north to Canada. As a teenager, he moved to Toronto and it was there that Bowles discovered his love of combat sports, namely boxing and wrestling. Although he preferred wrestling, he excelled quicker as a boxer, and while he never turned pro, the talented Bowles was a sparring partner for champions such as Henry Clark, George Foreman and Muhammad Ali. Meanwhile, he continued to pursue his passion and in 1964 the muscular 6’2″ 250 lb. rookie made his pro wrestling debut under the name Drew Glasteau. After gaining some experience in eastern Canada, Bowles began competing as (and, later, legally changed his name to) Rocky Johnson, in honor of his two favorite boxers, Rocky Marciano and Jack Johnson.

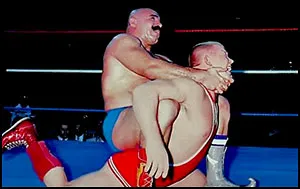

With lightning quick speed, tremendous strength and possessing a dropkick that was truly a thing of beauty, Johnson was already a main event talent and working at the top of the cards for major Canadian promotions like Frank Tunney’s Maple Leaf Wrestling, Stu Hart’s Stampede Wrestling, and Rod Fenton’s All Star Wrestling after just two years in the sport,. It was in Fenton’s Vancouver promotion that the young Johnson engaged in his first big feud (against John & Chris Tolos) and also won his first championship, the Canadian Tag Team title, with partner Don Leo Jonathan. Following his stay in Vancouver, Johnson travelled to the Detroit territory, where he teamed with Ben Justice to defeat the Hell’s Angels (Ron and Paul Dupree) on January 18, 1969 to win the NWA World Tag Team championship. After his stint in Detroit was finished, Johnson headed west to Los Angeles and almost immediately engaged in a major feud with the area’s top heel, “Classy” Fred Blassie. The rivalry between Johnson and Blassie was explosive, both in the ring and at the box office, and the two traded the prestigious Americas Heavyweight title four times between January of 1970 through June of the same year. While wrestling in the L.A. territory, Johnson also captured the NWA Beat the Champ Television Championship twice and the Americas Tag Team title (w/Earl Maynard).

With lightning quick speed, tremendous strength and possessing a dropkick that was truly a thing of beauty, Johnson was already a main event talent and working at the top of the cards for major Canadian promotions like Frank Tunney’s Maple Leaf Wrestling, Stu Hart’s Stampede Wrestling, and Rod Fenton’s All Star Wrestling after just two years in the sport,. It was in Fenton’s Vancouver promotion that the young Johnson engaged in his first big feud (against John & Chris Tolos) and also won his first championship, the Canadian Tag Team title, with partner Don Leo Jonathan. Following his stay in Vancouver, Johnson travelled to the Detroit territory, where he teamed with Ben Justice to defeat the Hell’s Angels (Ron and Paul Dupree) on January 18, 1969 to win the NWA World Tag Team championship. After his stint in Detroit was finished, Johnson headed west to Los Angeles and almost immediately engaged in a major feud with the area’s top heel, “Classy” Fred Blassie. The rivalry between Johnson and Blassie was explosive, both in the ring and at the box office, and the two traded the prestigious Americas Heavyweight title four times between January of 1970 through June of the same year. While wrestling in the L.A. territory, Johnson also captured the NWA Beat the Champ Television Championship twice and the Americas Tag Team title (w/Earl Maynard).

Having conquered L.A., Johnson’s next move was to Roy Shire’s San Francisco territory, which at the time was arguably the most talent-rich promotion in America. On September 18, 1971, Johnson teamed with Pepper Gomez to defeat the formidable team of Pat Patterson and “Superstar” Billy Graham for the NWA World Tag Team championship. “The Soul Man” also captured the area’s top prize, the U.S. Heavyweight championship, and held it for three months before being dethroned by Pat Patterson on February 12, 1972. However, a Patterson babyface turn later in the year led to an inspired pairing of Johnson & Patterson that resulted in three different NWA World Tag Team reigns for the popular duo between 1972-1973.

After leaving California, Johnson made several very successful territorial stops, most notable being Georgia. Texas, Memphis, and Florida. In Georgia, Johnson became the first African-American Georgia Heavyweight champion when he defeated Buddy Colt on December 6, 1974. While in the Peachtree State, he also won the Georgia Tag Team title, with partner Jerry Brisco, on January 26, 1975. In Memphis, Johnson engaged in a highly profitable feud with Jerry Lawler, defeating Lawler on November 1, 1976 for the NWA Southern Heavyweight title and drawing sellouts to the Mid South Coliseum on several occasions. Shortly after entering the Texas territory in 1976, Johnson won the Texas Heavyweight championship, as well as the Texas Tag Team title on March 3, 1976. In the Sunshine State, he defeated James J. Dillon to capture the Florida TV title on July 31, 1975, as well as the Florida Tag Team title (with partner Pedro Morales) on September 19, 1977. However, his biggest championship victory in Florida came when (just as he had done a few years earlier in Georgia) Rocky Johnson became the first African-American wrestler to win the Florida Heavyweight championship, defeating “Killer” Karl Kox on March 8, 1978. Johnson was also a frequent main-eventer in the St. Louis, Portland and Mid Atlantic promotions.

After leaving California, Johnson made several very successful territorial stops, most notable being Georgia. Texas, Memphis, and Florida. In Georgia, Johnson became the first African-American Georgia Heavyweight champion when he defeated Buddy Colt on December 6, 1974. While in the Peachtree State, he also won the Georgia Tag Team title, with partner Jerry Brisco, on January 26, 1975. In Memphis, Johnson engaged in a highly profitable feud with Jerry Lawler, defeating Lawler on November 1, 1976 for the NWA Southern Heavyweight title and drawing sellouts to the Mid South Coliseum on several occasions. Shortly after entering the Texas territory in 1976, Johnson won the Texas Heavyweight championship, as well as the Texas Tag Team title on March 3, 1976. In the Sunshine State, he defeated James J. Dillon to capture the Florida TV title on July 31, 1975, as well as the Florida Tag Team title (with partner Pedro Morales) on September 19, 1977. However, his biggest championship victory in Florida came when (just as he had done a few years earlier in Georgia) Rocky Johnson became the first African-American wrestler to win the Florida Heavyweight championship, defeating “Killer” Karl Kox on March 8, 1978. Johnson was also a frequent main-eventer in the St. Louis, Portland and Mid Atlantic promotions.

As athletic, talented and charismatic as Rocky Johnson was, it’s no wonder that he rose to the top of the wrestling world so quickly. Beginning in 1974, Johnson was receiving NWA title shots, first in scientific babyface vs. babyface matches with Jack Brisco before graduating to full-on bloodbaths with NWA kingpins Terry Funk, Harley Race and, eventually, Ric Flair.

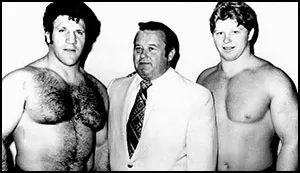

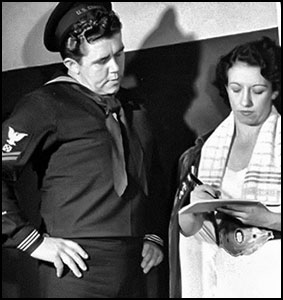

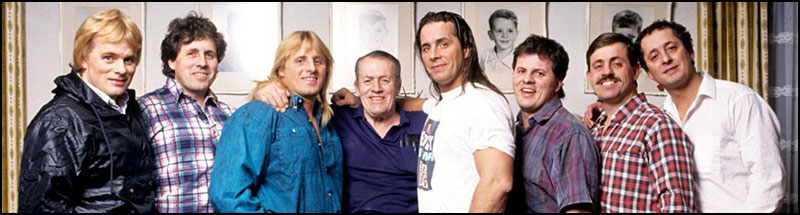

In 1982, Johnson entered the World Wrestling Federation and was soon paired with a manager, “Nature Boy” Buddy Rogers. With the sophisticated former champion in his corner, Johnson engaged in several major feuds, primarily with Don Muraco and Greg “The Hammer” Valentine, as well as with Adrian Adonis. However, his early-1980s run in the World Wrestling Federation is most remembered by his tag team with “Mr. USA” Tony Atlas, collectively known as The Soul Patrol. Together, Johnson and Atlas became the WWF’s first African-American tag team champions on November 15, 1983 when they defeated Lou Albano’s Wild Samoans in Allentown, Pennsylvania. The Soul Patrol had everything it took to be the best; strength, speed, experience, and talent. However, the one ingredient they lacked also happened to be essential for a long-lasting tag team… camaraderie. Ultimately, Johnson and Atlas just simply didn’t like each other. Which is a shame, because during their five months as tag champions, the powerhouse duo showed that they had everything needed to become a truly legendary team. But, it was not meant to be and The Soul Patrol met its demise on April 17, 1984 when they were defeated by The North/South Connection (Adrian Adonis & Dick Murdoch).

Following his run in the WWF, Johnson returned to Hawaii, where his mother-in-law ran Polynesian Pro Wrestling. While PPW had once been a thriving promotion, by the mid-1980s it was suffering through the same problems that most other smaller territories were experiencing at the time. That said, PPW was still able to draw some big houses and maintained strong ratings for its television program, and Johnson bought a management stake in the promotion, the same organization that was once run by his father-in-law, “High Chief” Peter Maivia. Unfortunately for all involved, including Johnson, Polynesian Pro soon met its demise and Johnson lost a great deal of his savings as a result. With no real options in terms of earning the kind of money wrestling provided, he returned to the ring despite his advancing age, working in Memphis and then smaller independents primarily throughout the northeast before officially retiring in 1991.

Following his run in the WWF, Johnson returned to Hawaii, where his mother-in-law ran Polynesian Pro Wrestling. While PPW had once been a thriving promotion, by the mid-1980s it was suffering through the same problems that most other smaller territories were experiencing at the time. That said, PPW was still able to draw some big houses and maintained strong ratings for its television program, and Johnson bought a management stake in the promotion, the same organization that was once run by his father-in-law, “High Chief” Peter Maivia. Unfortunately for all involved, including Johnson, Polynesian Pro soon met its demise and Johnson lost a great deal of his savings as a result. With no real options in terms of earning the kind of money wrestling provided, he returned to the ring despite his advancing age, working in Memphis and then smaller independents primarily throughout the northeast before officially retiring in 1991.

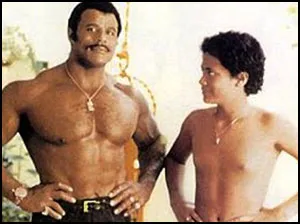

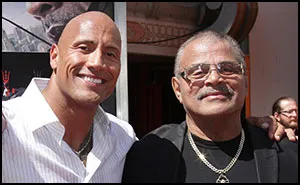

Rocky & Dwayne Johnson

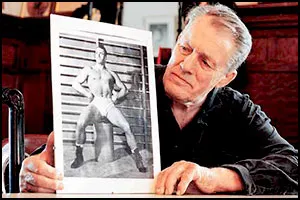

Not long after his retirement from pro wrestling, Johnson’s son Dwayne decided he wanted to try his hand at being a pro wrestler. Knowing the difficulties of a career inside of the squared circle, Rocky was skeptical at first, but, he eventually saw that Dwayne was serious about his decision and he agreed to train his son for a career in the ring. After spending some time working out with Dwayne and showing him the basics, Rocky felt that his son was capable enough to move on to the next phase. He made a call to his old friend (and high-level WWF employee) Pat Patterson, asking if he could come to Florida and take a look at Dwayne. Patterson agreed and the rest, as they say, is history. As for Rocky Johnson, he was later offered (and accepted) a job by the WWF to become a trainer/coach in Louisville, Kentucky at the promotion’s developmental group, Ohio Valley Wrestling, before permanently retiring from professional wrestling.

Rocky Johnson is a member of the St. Louis Wrestling Hall of Fame (2008) and the WWE Hall of Fame (2008). In December of 2019, just weeks before his death, Johnson joined the Board of Directors of the International Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame.

Rocky Johnson is a member of the St. Louis Wrestling Hall of Fame (2008) and the WWE Hall of Fame (2008). In December of 2019, just weeks before his death, Johnson joined the Board of Directors of the International Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame.

“Soul Man” Rocky Johnson passed away due to a heart attack caused by a pulmonary embolism on January 15, 2020 at the age of 75.

by Stephen Von Slagle

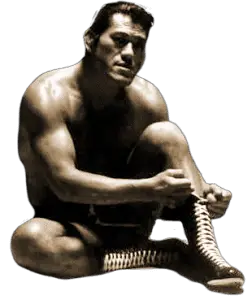

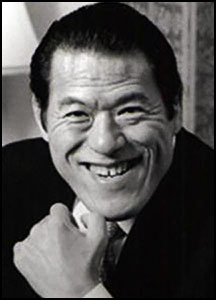

Whether it be as an athlete, promoter, trainer, businessman or politician, Antonio Inoki is undoubtedly one of wrestling’s most fascinating personalities. While some have accused Inoki of having an ego as large as the list of opponents he has defeated, there is no question that he spent the vast majority of his career trying to bring mainstream acceptance of, and respect to, professional wrestling. In many ways, Inoki served as wrestling’s unofficial Ambassador to the World and worked tirelessly to introduce the sport to nations that had never (or rarely) seen professional wrestling, countries such as China, Russia, Iraq, Korea and Taiwan. Many times throughout his lengthy career, Inoki faced champions of other combat sports in a unique effort to bring credibility to the sport of pro wrestling. Meanwhile, as a promoter of both pro wrestling and mixed martial arts, Inoki was often way ahead of the curve when it came to combat sports.

The founder of New Japan Pro Wrestling was born Kanji Inoki on Feb. 20, 1943 in Yokohama and, when he was in his early teens, moved with his family to Brazil. While in Brazil, Inoki established himself as a promising star in the sport of track & field, winning several regional medals before competing in the All-Brazilian championships. It was during this time period that the 6’2″ teenager caught the eye of Rikidozan, who recruited Inoki, convincing him to try his hand at professional wrestling. Inoki agreed and returned to Japan where, under the supervision of both Rikidozan and Karl Gotch, he (as well as Shohei Baba) began his training for a career inside of the squared circle. Competing for the Japan Wrestling Association, an eighteen year old Inoki made his professional debut on September 30, 1960, losing to Kintaro Ohki. During his first few years in the sport, Inoki wrestled exclusively for the JWA, where he gained valuable experience (as well as the name “Antonio,” which is said to have been given to him by his mentor Rikidozan, after the legendary Antonino Rocca) while learning the subtle nuances of his new profession. Eventually, though, it was felt that both Inoki and Baba, the JWA’s top two new performers, would be best served by travelling to the U.S. in order to learn the American aspects of pro wrestling. On June 24, 1964, Inoki (under the stereotypical ring-name of Tokyo Tom) defeated Joe Blanchard to gain the NWA Texas Heavyweight title in Houston and, several months later, Inoki (now wrestling as Kanji Inoki) teamed with Duke Keomuka in Dallas to win Texas’ version of the NWA World Tag Team title in 1965. From there, Inoki travelled to Nick Gulas & Roy Welch’s Tennessee promotion, where he teamed with Hiro Matsuda to capture their version of the NWA World Tag Team title on January 24, 1966 in Memphis.

The founder of New Japan Pro Wrestling was born Kanji Inoki on Feb. 20, 1943 in Yokohama and, when he was in his early teens, moved with his family to Brazil. While in Brazil, Inoki established himself as a promising star in the sport of track & field, winning several regional medals before competing in the All-Brazilian championships. It was during this time period that the 6’2″ teenager caught the eye of Rikidozan, who recruited Inoki, convincing him to try his hand at professional wrestling. Inoki agreed and returned to Japan where, under the supervision of both Rikidozan and Karl Gotch, he (as well as Shohei Baba) began his training for a career inside of the squared circle. Competing for the Japan Wrestling Association, an eighteen year old Inoki made his professional debut on September 30, 1960, losing to Kintaro Ohki. During his first few years in the sport, Inoki wrestled exclusively for the JWA, where he gained valuable experience (as well as the name “Antonio,” which is said to have been given to him by his mentor Rikidozan, after the legendary Antonino Rocca) while learning the subtle nuances of his new profession. Eventually, though, it was felt that both Inoki and Baba, the JWA’s top two new performers, would be best served by travelling to the U.S. in order to learn the American aspects of pro wrestling. On June 24, 1964, Inoki (under the stereotypical ring-name of Tokyo Tom) defeated Joe Blanchard to gain the NWA Texas Heavyweight title in Houston and, several months later, Inoki (now wrestling as Kanji Inoki) teamed with Duke Keomuka in Dallas to win Texas’ version of the NWA World Tag Team title in 1965. From there, Inoki travelled to Nick Gulas & Roy Welch’s Tennessee promotion, where he teamed with Hiro Matsuda to capture their version of the NWA World Tag Team title on January 24, 1966 in Memphis.

After a few years spent wrestling in America, it was time to return home to the JWA where, despite his undeniable talent and superior wrestling skills, Inoki once again found himself taking a backseat to his gigantic contemporary, Shohei Baba. With his mentor Rikidozan no longer a part of the promotion and feeling frustrated over what he perceived to be favoritism by the JWA towards Baba, Inoki left the JWA to form a partnership with Hisashi Shinma in 1966 and together they created the Tokyo Pro promotion. Ultimately, Tokyo Pro lasted for less that a year, however, away from the long shadow of Baba, Inoki was able to raise his standing in the eyes of the wrestling public via several high-profile, exciting matches, including a victory over the respected Johnny Valentine for the Tokyo Pro Heavyweight championship. When the short-lived Tokyo Pro folded, Inoki returned to the JWA in 1967 and formed a very successful team with Baba. Not surprisingly, the Japanese “dream team” of Inoki & Baba were an instant success, winning the International Tag Team championship on four different occasions between 1967-1969. Additionally, Inoki captured the JWA’s prestigious United National championship in 1971. However, with the late Rikidozan no longer in control of the JWA, there was a feeling that the ship was without a captain and, consequently, several members of the promotion’s roster were not happy with the direction of the company. As a result, there was a mutiny of sorts and, in the later part of 1971, Inoki was fired for participating in what ended up being a failed takeover of the JWA

Following his dismissal from the JWA, Antonio Inoki founded the company that would ultimately become Japan’s most successful and influential wrestling promotion, New Japan Pro Wrestling, in 1972. In retrospect, it was a telling sign that Inoki’s first NJPW match was against his former trainer and renowned shooter, Karl Gotch. Throughout the course of the promotion’s history, NJPW espoused a philosophy that sought to bring credibility to professional wrestling vis-à-vis the reality-based “worked shoot.” And, while not exclusive to New Japan, the method of professional wrestling that is now commonly known as “strong style” was very much popularized, at least in part, by Inoki’s NJPW Stemming from the ideology of its founder, logical booking combined with hard hitting, fundamentally sound, realistic in-ring action have been the hallmarks of New Japan since the promotion’s inception. That said, there was one (very important) aspect of promoting that Inoki failed to capitalize upon which, at least during the early years of NJPW, relegated his promotion to a place that was secondary to Shohei Baba’s All Japan Pro Wrestling. As a respected member of the National Wrestling Alliance, Baba had first pick of the best American wrestlers in the world as well as being able to book NWA World championship matches on AJPW cards. Due to Baba’s good standing in the Alliance, Inoki was initially locked out of the NWA during New Japan’s early years, as well as the top American talent that membership would provide. As a result, New Japan Pro Wrestling, as exemplary as it may have been, simply could not compete on an even footing with Baba’s AJPW during the early years of the Japanese promotional war. With no other recourse, Inoki purchased the Ohio-based National Wrestling Federation (NWF) and its regionally respected World Heavyweight title, which Inoki won on four different occasions between 1973-1981. More importantly, Inoki’s purchase ensured that he at least had some access to American talent, as well as a relatively prestigious “world” championship to promote on his NJPW cards. Nearly a decade later, Inoki retired the NWF title when the I.W.G.P. championship was introduced and it became NJPW’s top prize.

In addition to creating NJPW, Inoki was the founder of several other important, trend-setting promotions and events over the years. Of course, there was the famous 1995 “Festival for Peace” two-day event in North Korea that involved both NJPW and WCW and drew audiences of 150,000 and 190,000 to the Rungnado May Day Stadium. Additionally, he promoted major pro wrestling and MMA events such as the Ultimate Crush, which combined both wrestling and MMA on the same cards. With the late-1990s came Inoki’s United Fighting-arts Organization. Along with former student and mixed martial arts pioneer Satoru Sayama, Inoki created U.F.O., an early MMA styled group that spotlighted former World judo champion, Olympian and two-time NWA champion, Naoya Ogawa. Inoki also introduced the annual Inoki Bom-Ba-Ya events. Taking place from 2001-2003, these New Years Eve cards showcased premier professional wrestlers going up against top MMA fighters. After selling his controlling stock in New Japan to Yuke’s (a successful Japanese video game company) in 2005, Inoki started the Inoki Genome Federation, which was a group that featured both professional wrestling and mix martial arts, in 2007. The first IGF show, which was held on June 29, 2007 at the Sumo Hall in Tokyo, featured a main event that matched former WWE champion and Olympic gold medalist Kurt Angle against former N.C.A.A. heavyweight and reigning I.W.G.P. champion Brock Lesnar. The I.G.F. also promoted cards in North Korea, a true rarity, presenting two shows in Pyongyang, North Korea during the summer of 2014. Also of note, in December of 2014, the I.G.F. announced that it had struck a deal with the Chinese video streaming website PPTV that would brings its programming to Chinese fans.

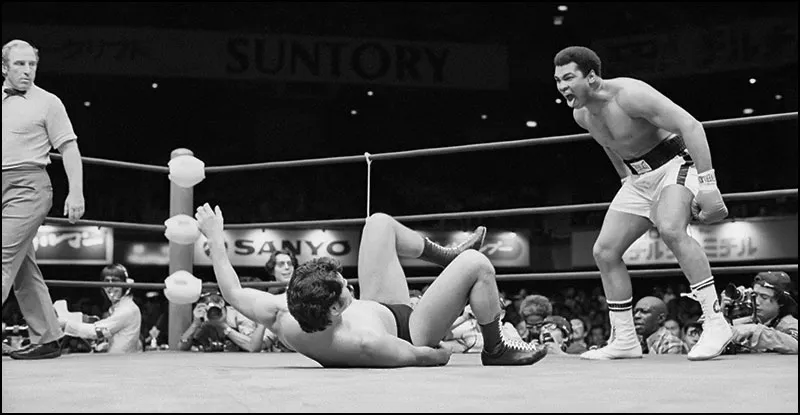

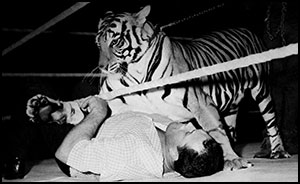

Inoki’s forward-thinking approach to promotion pre-dated the formation of MMA by many years and he was known for facing opponents from all disciplines of combat sports (usually in worked matches) long before the rise of UFC, Pride or other mixed martial arts promotions. Of course, there was his infamous Wrestler vs. Boxer match against Muhammed Ali in 1976 that went to a draw. However, previous to his controversial shoot against Ali, Inoki “defeated” Willem Ruska, an Olympic gold medalist in judo. Following the bout with Ali, Inoki, in his unending quest to bring respect and legitimacy to professional wrestling, also emerged victorious against karate champions Everett Eddy and Willie Williams, boxer Chuck Wepner, Judo Olympic medalist Allen Coage (a.k.a Bad News Allen), and, many years later, mixed martial artist Renzo Gracie.

During his long and successful career, Inoki won numerous titles including, among others, the NWA North American Tag Team Championship (w/Seiji Sakaguchi), three All-Asian Tag Team titles (twice w/Michiak Yoshimura and once w/ Kintaro Ohki), the U.W.A. (Mexico) World Heavyweight title, three I.W.G.P. Heavyweight championships, and WWWF World Martial Arts Heavyweight Championship (twice). Inoki also won an incredible 19 tournaments in Japan, defeating dozens of top wrestlers such as Tatsumi Fujinami, Dick Murdoch, Andre The Giant (twice), Stan Hansen (4 times), and Sting.

In 1979, Inoki was involved in a very controversial title switch involving Bob Backlund and the WWF Heavyweight title. On November 30, 1979 in Tokushima, Japan, Backlund was pinned by Inoki, as planned, for the WWF championship. The following week, the two wrestlers had a rematch, and this time Backlund appeared to have regained his championship. However, going against the agreed upon plan, then-WWF President Hisashi Shinma declared the match a “no-contest” because of interference from Tiger Jeet Singh and Shinma allowed Inoki to keep the title. Inoki was scheduled to defend his WWF World Martial Arts championship a month later in New York (against Hussein Arab a.k.a. The Iron Sheik) which was to be broadcast live in Japan. The hope was to have the Japanese public see their champion defend his new title at Madison Square Garden, an unprecedented and very prestigious occurrence for Inoki (or any other Japanese wrestler) at that time in history. However, the WWF refused to acknowledge the title switch and Vince McMahon, Sr. worked out a storyline compromise that explained why Inoki wasn’t the WWF champion, stating that Inoki had refused to accept the title victory due to Signh’s interference. A match between Backlund and “Big, Bad” Bobby Duncum on December 12, 1979 in New York City took place to decide the winner of the “held up” WWF title, with Backlund winning. Ironically, American fans never knew of the controversy in Japan, and thought the Backlund/Duncum match was just another regular monthly title defense for Backlund. The WWF has never acknowledged the title switch and to this day does not count Inoki as a former WWE Heavyweight champion.

In 1989, while still an active competitor, Inoki entered the world of politics and was elected to the House of Counsellors (the Japanese equivalent of the U.S. Senate), running as a representative of his own Sports and Peace Party. Ever the promoter, Inoki staged the “Peace Festival” in Baghdad for December 3, 1990, just prior to the start of the Gulf War. When Saddam Hussein’s government released 41 Japanese hostages just as the Peace Festival was taking place, Inoki was able to claim, whether true or not, that he was directly responsible for negotiating the release of his countrymen. As a result, he was easily able to retain his seat in the 1992 House of Counsellors election. However, when his longtime friend and business partner Shinma went public with accusations of tax evasion and embezzlement, accusations that were later confirmed, Inoki failed to retain his seat in the 1995 election. Nearly twenty years later, though, Inoki returned to politics and won a seat in the Japanese Diet, running on the Japan Restoration Party ticket in 2013. However, he again ran into more controversy when he was suspended from the Diet for a period of 30 days due to an unauthorized trip to North Korea, Japan’s longtime enemy, on the 60th anniversary of the armistice in the Korean War. His ongoing mission to establish a peaceful rapport with North Korea was seen as disrespectful by some within the Japanese government (and population) but also viewed by others as a necessary step in order to establish a lasting peace between the neighboring nations. In 2012, Inoki revealed that he had converted to Shia Islam while on a pilgrimage to the Shiite holy city of Karbala during his 1990 trip to Iraq. He also announced that he had changed his name to Muhammad Hussain Inoki. In the summer of 2019, Inoki permanently retired from politics.

In 1989, while still an active competitor, Inoki entered the world of politics and was elected to the House of Counsellors (the Japanese equivalent of the U.S. Senate), running as a representative of his own Sports and Peace Party. Ever the promoter, Inoki staged the “Peace Festival” in Baghdad for December 3, 1990, just prior to the start of the Gulf War. When Saddam Hussein’s government released 41 Japanese hostages just as the Peace Festival was taking place, Inoki was able to claim, whether true or not, that he was directly responsible for negotiating the release of his countrymen. As a result, he was easily able to retain his seat in the 1992 House of Counsellors election. However, when his longtime friend and business partner Shinma went public with accusations of tax evasion and embezzlement, accusations that were later confirmed, Inoki failed to retain his seat in the 1995 election. Nearly twenty years later, though, Inoki returned to politics and won a seat in the Japanese Diet, running on the Japan Restoration Party ticket in 2013. However, he again ran into more controversy when he was suspended from the Diet for a period of 30 days due to an unauthorized trip to North Korea, Japan’s longtime enemy, on the 60th anniversary of the armistice in the Korean War. His ongoing mission to establish a peaceful rapport with North Korea was seen as disrespectful by some within the Japanese government (and population) but also viewed by others as a necessary step in order to establish a lasting peace between the neighboring nations. In 2012, Inoki revealed that he had converted to Shia Islam while on a pilgrimage to the Shiite holy city of Karbala during his 1990 trip to Iraq. He also announced that he had changed his name to Muhammad Hussain Inoki. In the summer of 2019, Inoki permanently retired from politics.

Regarding the subject of retirement, in 1994 Antonio Inoki announced his “Final Countdown” tour, which was to be a series of matches that would culminate in his retirement from professional wrestling. During the tour, which ended up lasting four full years, Inoki revisited some of his most important matches, including his noteworthy MMA bouts, in addition to squaring off in the ring one last time against several top rivals from the past. His final match in America took place at WCW’s Clash of the Champions XXVIII, where he defeated WCW World Television champion Lord Steven Regal in a non-title encounter. The last stop on Inoki’s “Final Countdown” took place on April 4, 1998 at the Tokyo Dome before nearly 70,000 fans when he faced and defeated Don Frye, thus ending his 37-year career as a professional wrestler.

In addition to being a wrestler, promoter, businessman and politician, Inoki is one of professional wrestling’s most prolific trainers and he was instrumental in helping top grapplers such as Satoru Sayama, Tatsumi Fujinami, Keiji Muto, Masahiro Chono, Akira Maeda, Hiroshi Hase, Riki Choshu, Naoya Ogawa, Nobuhiko Takada, and dozens of other legendary Japanese wrestlers to learn their craft. Inoki is also responsible for training several American wrestlers, including Brian “Crush” Adams, “Bad News” Allen, Rocky Romero and T.J. Perkins.

In addition to being a wrestler, promoter, businessman and politician, Inoki is one of professional wrestling’s most prolific trainers and he was instrumental in helping top grapplers such as Satoru Sayama, Tatsumi Fujinami, Keiji Muto, Masahiro Chono, Akira Maeda, Hiroshi Hase, Riki Choshu, Naoya Ogawa, Nobuhiko Takada, and dozens of other legendary Japanese wrestlers to learn their craft. Inoki is also responsible for training several American wrestlers, including Brian “Crush” Adams, “Bad News” Allen, Rocky Romero and T.J. Perkins.

Muhammad Hussain “Antonio” Inoki is a member of the WCW Hall of Fame (1995), the Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Fame (1996), the International Wrestling Institute & Museum’s George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame (2005), the Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame (2009) and the WWE Hall of Fame (2010).

by Stephen Von Slagle

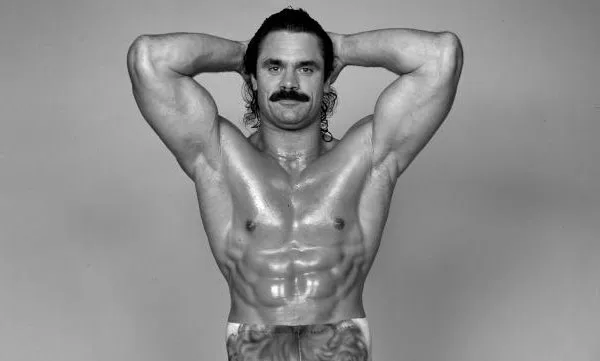

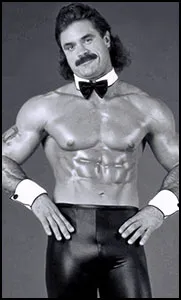

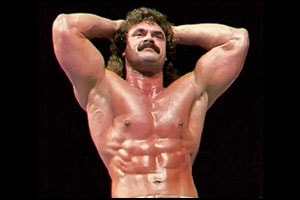

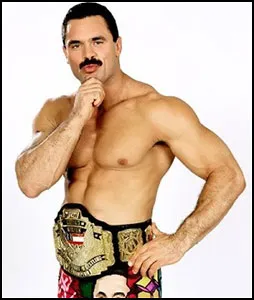

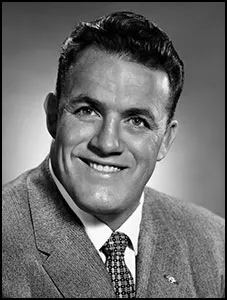

Wrestling history has proven that with each new generation of performer comes a few special men who, in their own individual way, alter the “sport” and change it from what it was to what it would become. Certainly, the talented and trend-setting wrestler known worldwide as “Ravishing” Rick Rude falls into that elite category which is reserved for those who have truly reshaped the wrestling business and influenced others to come. “Ravishing” Rick Rude’s long-term influence and impact on professional wrestling is more than apparent to the trained eye. “The Ravishing One” was truly a revolutionary force in pro wrestling, although not necessarily due to his ring work, solid as it may have been. Instead, Rude left his indelible mark on wrestling through his look, his attitude, and most importantly, his unique style of delivering a promo. While it is now commonplace for a wrestler to stroll down to the ring while using the microphone to insult (or excite) the audience, or to start each of his wrestling matches by cutting an in-ring promo first, neither was the case when Rude began his career. Indeed, these traits, common in so many of today’s performers, didn’t really exist until the muscular, aggressive and arrogant “Smooth Operator” introduced them (as well as other nuances, including air-brushed wrestling gear) during the early and mid-Eighties.

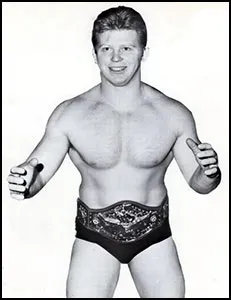

“Ravishing” Rick Rude was born Richard Erwin Rood on December 7, 1958 and grew up just outside of Minneapolis, in Robbinsdale, Minnesota. Following high school, he attended Anoka Ramsey Junior College and graduated with a degree in physical education. After finishing college, he still had not found his calling and was working as a bouncer when fate intervened and he was approached about pursuing a career in pro wrestling. Having been a fan of the sport while growing up, Rood quickly decided to give wrestling a shot and he was soon being trained by Eddie Sharkey. After his training was complete, Rood (a former arm-wrestling champion) began his wrestling career in 1983, performing on a card held in Vancouver, British Columbia. Following a short stay in the Northwestern territory, he then moved on to Georgia, where he was used as an enhancement talent before travelling to the Memphis territory. While in Memphis, he was seconded by the region’s top manager, “The Mouth of the South” Jimmy Hart. Of course, as Hart’s top protégé, Rood couldn’t help but get involved in a feud with Memphis legend Jerry “The King” Lawler. In a truly impressive victory for someone with just a year of experience to his credit, Rood defeated Lawler for the prestigious AWA Southern Heavyweight title on June 11, 1984 before a raucous, packed crowd at the Mid-South Coliseum. As a key member of Jimmy Hart’s “First Family,” Rood, despite his inexperience, became a main-event player in the territory and shortly after losing the Southern championship to Tommy Rich, he was back in the title picture once more. With fellow First Family member, the young & massive King Kong Bundy, Rood captured the AWA Southern Tag Team championship on October 8, 1984, adding yet another impressive title to his growing championship resume. Six months after losing the AWA Southern Heavyweight title, the talented young heel travelled to Florida and capturing the NWA’s even more prestigious version of the championship. On January 16, 1985 in Tampa, Florida, Rood continued his steady drive to the top when he won the NWA Southern Heavyweight title by defeating “Pistol” Pez Whatley. A dominant Southern champion, Rood, led by his new manager, Percival Pringle III (a.k.a. Paul Bearer) held the territory’s primary title for three months, defending his Southern championship against several of Florida’s top fan favorites such as Whatley, Wahoo McDaniel, Billy Jack Haynes and Mike Graham among others before eventually dropping the belt to Brian Blair.

“Ravishing” Rick Rude was born Richard Erwin Rood on December 7, 1958 and grew up just outside of Minneapolis, in Robbinsdale, Minnesota. Following high school, he attended Anoka Ramsey Junior College and graduated with a degree in physical education. After finishing college, he still had not found his calling and was working as a bouncer when fate intervened and he was approached about pursuing a career in pro wrestling. Having been a fan of the sport while growing up, Rood quickly decided to give wrestling a shot and he was soon being trained by Eddie Sharkey. After his training was complete, Rood (a former arm-wrestling champion) began his wrestling career in 1983, performing on a card held in Vancouver, British Columbia. Following a short stay in the Northwestern territory, he then moved on to Georgia, where he was used as an enhancement talent before travelling to the Memphis territory. While in Memphis, he was seconded by the region’s top manager, “The Mouth of the South” Jimmy Hart. Of course, as Hart’s top protégé, Rood couldn’t help but get involved in a feud with Memphis legend Jerry “The King” Lawler. In a truly impressive victory for someone with just a year of experience to his credit, Rood defeated Lawler for the prestigious AWA Southern Heavyweight title on June 11, 1984 before a raucous, packed crowd at the Mid-South Coliseum. As a key member of Jimmy Hart’s “First Family,” Rood, despite his inexperience, became a main-event player in the territory and shortly after losing the Southern championship to Tommy Rich, he was back in the title picture once more. With fellow First Family member, the young & massive King Kong Bundy, Rood captured the AWA Southern Tag Team championship on October 8, 1984, adding yet another impressive title to his growing championship resume. Six months after losing the AWA Southern Heavyweight title, the talented young heel travelled to Florida and capturing the NWA’s even more prestigious version of the championship. On January 16, 1985 in Tampa, Florida, Rood continued his steady drive to the top when he won the NWA Southern Heavyweight title by defeating “Pistol” Pez Whatley. A dominant Southern champion, Rood, led by his new manager, Percival Pringle III (a.k.a. Paul Bearer) held the territory’s primary title for three months, defending his Southern championship against several of Florida’s top fan favorites such as Whatley, Wahoo McDaniel, Billy Jack Haynes and Mike Graham among others before eventually dropping the belt to Brian Blair.

Dallas’ World Class Championship Wrestling was next up for Rood, who by this time had begun referring to himself as “The Smooth Operator.” As always, Rood quickly won championship gold upon entering this latest territory, courtesy of his devastating variation of the Neck Breaker known as “The Rude Awakening.” With the annoying, agitating Percy Pringle still by his side and the sophisticated strains of Sade’s Smooth Operator serving as his entrance theme, the arrogant, rule breaking newcomer created quite a stir in Texas by winning the NWA American Heavyweight title almost immediately upon his arrival. Defeating “Iceman” King Parsons for the championship on November 4, 1985 in Ft. Worth, Texas, Rick Rood instantly became the top heel in Texas, a distinction he would enjoy for quite some time to come. While in the WCWA, Rood also captured the World Class TV title by defeating the “cousin” of the famous Von Erich brothers, Lance Von Erich, and he held the belt until being defeated by Bruiser Brody. By the end of 1986, having conquered the World Class territory, it was time for “The Smooth Operator” to make his next career move by leaving the WCWA and moving up to Jim Crockett’s successful NWA promotion, seen nationally via syndication and on TBS. Soon after his NWA debut, “The Ravishing One” (who now spelled his name Rude instead of Rood) debuted as a member of “Number One” Paul Jones’ army.

Dallas’ World Class Championship Wrestling was next up for Rood, who by this time had begun referring to himself as “The Smooth Operator.” As always, Rood quickly won championship gold upon entering this latest territory, courtesy of his devastating variation of the Neck Breaker known as “The Rude Awakening.” With the annoying, agitating Percy Pringle still by his side and the sophisticated strains of Sade’s Smooth Operator serving as his entrance theme, the arrogant, rule breaking newcomer created quite a stir in Texas by winning the NWA American Heavyweight title almost immediately upon his arrival. Defeating “Iceman” King Parsons for the championship on November 4, 1985 in Ft. Worth, Texas, Rick Rood instantly became the top heel in Texas, a distinction he would enjoy for quite some time to come. While in the WCWA, Rood also captured the World Class TV title by defeating the “cousin” of the famous Von Erich brothers, Lance Von Erich, and he held the belt until being defeated by Bruiser Brody. By the end of 1986, having conquered the World Class territory, it was time for “The Smooth Operator” to make his next career move by leaving the WCWA and moving up to Jim Crockett’s successful NWA promotion, seen nationally via syndication and on TBS. Soon after his NWA debut, “The Ravishing One” (who now spelled his name Rude instead of Rood) debuted as a member of “Number One” Paul Jones’ army.

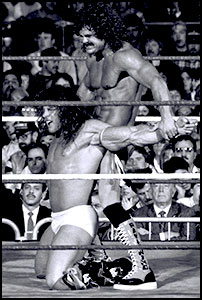

After a short run as a singles competitor, Rude was paired with “The Ragin’ Bull” Manny Fernandez and together they pulled off a major upset by defeating NWA tag champs The Rock `N Roll Express just weeks after forming their team. While, at first, their pairing seemed a bit awkward, Rude and Fernandez soon gelled into a very formidable team and capable World champions. Together, Jones’ seemingly make-shift team carried the World Tag Team title belts for more than a half-year. Still, despite his lengthy run as a co-holder of the tag team championship, Rude felt, perhaps rightly so, that he was not reaching his full potential in the NWA. So, when the opportunity arose in mid-1987, Rude, still one-half of the NWA World Tag Team champions, gave his notice and made the jump from the NWA to the WWF. Fernandez was allowed to replace the “injured” Rude with fellow Paul Jones stablemate Ivan Koloff, while “Ravishing” Rick Rude made his WWF debut soon thereafter.

As was often the case with wrestlers who coming into the WWF for the first time, once he entered the Federation, “Ravishing” Rick, despite the name he had built up for himself in the WCWA and NWA, was forced to prove himself all over again by starting at the bottom of the card and working his way up. Still, it didn’t take long for the impressive heel to catch on with both the WWF’s fans and management. Rude’s antagonistic, yet brilliant, pre-match ritual of getting on the microphone, insulting the audience, telling the sound man to “hit my music” and then slowly disrobing while gyrating his hips was a spectacle indeed. Designed to incite a negative reaction, the gimmick more than elicited the desired response and, before he knew it, Rude found himself amongst the most ‘hated’ men in the WWF and definitely on his way up the card towards the main event. Later, Rude accentuated his controversial pre-match ritual by incorporating a post-match gimmick in which he would have his manager, Bobby “The Brain” Heenan, pick an attractive lady from the audience and bring her into the ring. Rude would then celebrate his victory by kissing the female audience member passionately before softly laying her down on the mat. As though this was not enough of an ego-stroke, Rude would then proceed to stand over the fallen female, gyrating his hips and posing for the fans in a display that could be described as nothing but exploitative. Of course, that was the intention of the gimmick and it worked to perfection, especially when Rude tried it on the wife of none other than Jake “The Snake” Roberts, who was sitting in the audience and was “unknowingly” selected by Heenan. The ensuing feud between Roberts and Rude was among the most heated and emotional in WWF history and their matches never failed to create a great deal of excitement.

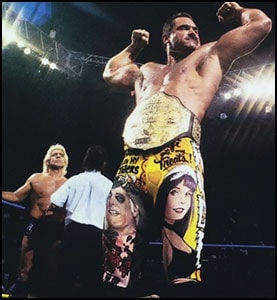

Additionally, by engaging in such a successful feud against an opponent the caliber of Jake Roberts, who at that point was in his WWF prime, Rude was finally elevated to the upper echelon of the promotion’s talent-rich roster.After paying his dues for the better part of a year and having proven himself during his feud with Roberts, Rude’s rise up the WWF’s crowded ranks was complete and his patience and talent were finally rewarded. Following an angle in which the egocentric Rude challenged any WWF superstar to a pose-down contest, the call was answered by none other than the superhuman Ultimate Warrior. The two bodybuilders then began a very successful program that culminated in Rude defeating The Warrior for the WWF’s second most prestigious title, the Intercontinental championship, on April 2, 1989 at WrestleMania in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Later, after the Ultimate Warrior had become WWF champion, Rude served as his top challenger during a large portion of the Warrior’s title reign.

Additionally, by engaging in such a successful feud against an opponent the caliber of Jake Roberts, who at that point was in his WWF prime, Rude was finally elevated to the upper echelon of the promotion’s talent-rich roster.After paying his dues for the better part of a year and having proven himself during his feud with Roberts, Rude’s rise up the WWF’s crowded ranks was complete and his patience and talent were finally rewarded. Following an angle in which the egocentric Rude challenged any WWF superstar to a pose-down contest, the call was answered by none other than the superhuman Ultimate Warrior. The two bodybuilders then began a very successful program that culminated in Rude defeating The Warrior for the WWF’s second most prestigious title, the Intercontinental championship, on April 2, 1989 at WrestleMania in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Later, after the Ultimate Warrior had become WWF champion, Rude served as his top challenger during a large portion of the Warrior’s title reign.

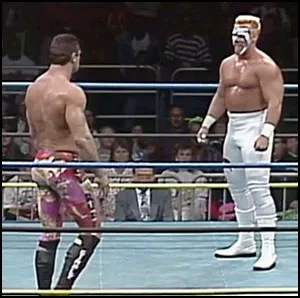

But, several injuries forced Rude to the sidelines and he was slowly written out of the WWF storylines. Month after month passed, more than a year in all, yet nothing was heard from the “Ravishing One.” However, this would change, drastically, in 1991 following a shocking surprise jump from the WWF to WCW which resulted in his unexpected debut on an episode of TBS’s Clash of the Champions. “Ravishing” Rick Rude immediately became the key player in Paul E. Dangerously’s impressive collection of wrestlers known as The Dangerous Alliance. In the tradition of the Four Horsemen, Rude’s Dangerous Alliance partners (“Stunning” Steve Austin, Larry Zbyszko, “The Enforcer” Arn Anderson, Bobby Eaton and Madusa) were always there to give him a bit of “back-up” should the need arise, which it often did. On November 19, 1991, “Simply Ravishing” Rick Rude became the NWA United States champion by defeating the promotion’s franchise player, reigning U.S. champion Sting. In WCW, Rude picked up right where he had left off in the WWF, showcasing his familiar entrance in which he would come out to the ring and tell all of the “fat, out of shape, cable-watching couch potatoes” to “sit down, shut up and watch” as he took his robe off and showed everyone “what a real man is supposed to look like.” Following his WCW debut, it was very apparent that Rude’s skills had not diminished during his absence from wrestling, but rather, he was better in the ring than ever before. Indeed, Rude’s sense of timing, his believable selling & bumping, and an expanded arsenal of both offensive and defensive moves combined to make him one of the best wrestlers in the world, a distinction that he had not earned while competing in the WWF. Following his title victory, Rude dominated the U.S. championship like few in WCW history. When facing top-level competition such as Sting, The British Bulldog, Dustin Rhodes and Ricky “The Dragon” Steamboat, proved that he was as good as it got. Not surprisingly, his solid ring work, heat-generating mic skills and abrasive, arrogant personality (not to mention his controversial manager, Paul E. Dangerously) all added up to an incredibly entertaining performer and, without question, “Ravishing” Rick Rude was WCW’s top heel during this time period.

On paper, it would seem that a feud between the egomaniacal “Ravishing” Rick Rude and longtime WCW-NWA champion “Nature Boy” Ric Flair over both the World title and Flair’s valet would be a sure-fire success both artistically and monetarily. And, in practice, it most definitely was, although their program was relatively short. The two superstars, who actually shared more than a few similarities, began their exciting run against each other following an episode of Ric Flair’s WCW Saturday Night talk segment called “A Flair for the Gold.” During the segment, “The Ravishing One” seemed more than a bit jealous of the attention that Flair, the NWA World Heavyweight champion, was receiving from his beautiful young French valet, Fifi. Considering himself to be the ultimate male specimen, “The Smooth Operator’s” out of control ego could not handle the fact that Fifi was more attracted to “The Nature Boy” than to him. Furthermore, Rude’s ambition turned to professional jealousy as he prepared to face the multi-time NWA-WWF-WCW World champion. Determined to prove that he was, indeed, better than the best, Rude focused on Flair’s valet in order to lure the champion into granting him a title match. Finally, after interrupting several of Flair’s interviews, incessantly harassing “The Nature Boy’s” valet with his unwanted advances and even going so far as to kiss Fifi against her will, an angered Flair readily granted Rude his title matches, which took place in arenas across the country. While “Slick” Ric was able to defend his title successfully against the younger, stronger Rude, “The Ravishing One” eventually got the best of Flair and on September 19, 1993 in Houston, Texas, Rude used a pair of brass knuckles to K.O. the champion and won the NWA World Heavyweight title.

On paper, it would seem that a feud between the egomaniacal “Ravishing” Rick Rude and longtime WCW-NWA champion “Nature Boy” Ric Flair over both the World title and Flair’s valet would be a sure-fire success both artistically and monetarily. And, in practice, it most definitely was, although their program was relatively short. The two superstars, who actually shared more than a few similarities, began their exciting run against each other following an episode of Ric Flair’s WCW Saturday Night talk segment called “A Flair for the Gold.” During the segment, “The Ravishing One” seemed more than a bit jealous of the attention that Flair, the NWA World Heavyweight champion, was receiving from his beautiful young French valet, Fifi. Considering himself to be the ultimate male specimen, “The Smooth Operator’s” out of control ego could not handle the fact that Fifi was more attracted to “The Nature Boy” than to him. Furthermore, Rude’s ambition turned to professional jealousy as he prepared to face the multi-time NWA-WWF-WCW World champion. Determined to prove that he was, indeed, better than the best, Rude focused on Flair’s valet in order to lure the champion into granting him a title match. Finally, after interrupting several of Flair’s interviews, incessantly harassing “The Nature Boy’s” valet with his unwanted advances and even going so far as to kiss Fifi against her will, an angered Flair readily granted Rude his title matches, which took place in arenas across the country. While “Slick” Ric was able to defend his title successfully against the younger, stronger Rude, “The Ravishing One” eventually got the best of Flair and on September 19, 1993 in Houston, Texas, Rude used a pair of brass knuckles to K.O. the champion and won the NWA World Heavyweight title.

Following his run with Flair, Rude’s ongoing feud with Sting was rekindled and the two superstars resumed their exciting series, with the WCW International World Heavyweight championship on the line. Being evenly matched opponents and with their individual ring strengths complimenting the other well, Sting and Rude engaged in several highly memorable and entertaining bouts during this phase of their feud, which had actually began some three years earlier. Eventually, Sting overcame Rude and defeated him for the championship on April 17, 1994 at the inaugural WCW Spring Stampede PPV, which was held at the Rosemont Horizon in suburban Chicago. Then, just a few weeks later on May 1, 1994, Rude’s career was forever altered when he met & defeated Sting in a rematch for the title in Fukuoka, Japan. During the hard-fought bout with Sting, Rude suffered a severe neck injury, one that effectively ended his in-ring career. The title was held up and then, eventually, regained by Sting while Rude disappeared from the wrestling scene as he tried to recover from the injury and subsequent surgery. Shockingly, it appeared that the talented Rude, who was in the middle of his prime as a wrestler, would never step into the ring and perform again. Sadly, that turned out to be the case. Fortunately, however, his premature retirement from the ring would not mark the end of “Ravishing” Rick Rude’s association with pro wrestling.

Following his run with Flair, Rude’s ongoing feud with Sting was rekindled and the two superstars resumed their exciting series, with the WCW International World Heavyweight championship on the line. Being evenly matched opponents and with their individual ring strengths complimenting the other well, Sting and Rude engaged in several highly memorable and entertaining bouts during this phase of their feud, which had actually began some three years earlier. Eventually, Sting overcame Rude and defeated him for the championship on April 17, 1994 at the inaugural WCW Spring Stampede PPV, which was held at the Rosemont Horizon in suburban Chicago. Then, just a few weeks later on May 1, 1994, Rude’s career was forever altered when he met & defeated Sting in a rematch for the title in Fukuoka, Japan. During the hard-fought bout with Sting, Rude suffered a severe neck injury, one that effectively ended his in-ring career. The title was held up and then, eventually, regained by Sting while Rude disappeared from the wrestling scene as he tried to recover from the injury and subsequent surgery. Shockingly, it appeared that the talented Rude, who was in the middle of his prime as a wrestler, would never step into the ring and perform again. Sadly, that turned out to be the case. Fortunately, however, his premature retirement from the ring would not mark the end of “Ravishing” Rick Rude’s association with pro wrestling.

After several years away from the public eye, Rude finally made yet another shocking, unexpected return to the business when he entered Extreme Championship Wrestling as Joey Style’s part-time color commentator and ECW World Champion “The Franchise” Shane Douglas’ full-time antagonist. The recipient of the fans’ cheers for the first time in more than a decade, Rude did not actually wrestle Douglas, but he nevertheless drove the egotistical ECW champion nearly insane with jealousy and anger during their obscenity-laced exchanges. Eventually, though, the plotline developed to the point where Rude and Douglas (along with The Franchise’s insatiable valet Francine) actually joined forces, creating The Triple Threat, an elite Horsemen-esque faction led by Douglas that featured Rude serving as a manager/advisor/run-in man.

Having proven his value as a performer despite his inability to wrestle, Rude (who was still in tremendous physical condition, aside from his vulnerable neck & back) attracted the eye of WWF management during his stay in ECW, and his former employer eventually offered Rude a new spot in the company, in which he would serve as a bodyguard for Shawn Michaels and D-Generation X. But, true to form, several months after his return to the WWF, Rude once again shocked the wrestling world when he appeared on WCW’s live Monday Nitro while being featured at nearly the exact same time on the WWF’s taped Monday Night Raw program. Joining forces with his longtime friend, nWo member Curt Hennig, Rude’s bold jump was completely unanticipated by both the public and the WWF, which was again embarrassed by WCW President Eric Bischoff’s ability to continually one-up the Federation. Yet, while his simultaneous WCW-WWF appearance was definitely an unexpected event that made a lot of waves initially, the impact of his return (as well as his overall job security) was undoubtedly lessened by Rude’s inability to wrestle. Having not competed since his neck was injured nearly five years earlier and without many career options left in wrestling, Rude decided that he was healthy enough to make a return to the ring as a wrestler. With his comeback decided upon, the former World champion began training intensely for his imminent return to action.

Having proven his value as a performer despite his inability to wrestle, Rude (who was still in tremendous physical condition, aside from his vulnerable neck & back) attracted the eye of WWF management during his stay in ECW, and his former employer eventually offered Rude a new spot in the company, in which he would serve as a bodyguard for Shawn Michaels and D-Generation X. But, true to form, several months after his return to the WWF, Rude once again shocked the wrestling world when he appeared on WCW’s live Monday Nitro while being featured at nearly the exact same time on the WWF’s taped Monday Night Raw program. Joining forces with his longtime friend, nWo member Curt Hennig, Rude’s bold jump was completely unanticipated by both the public and the WWF, which was again embarrassed by WCW President Eric Bischoff’s ability to continually one-up the Federation. Yet, while his simultaneous WCW-WWF appearance was definitely an unexpected event that made a lot of waves initially, the impact of his return (as well as his overall job security) was undoubtedly lessened by Rude’s inability to wrestle. Having not competed since his neck was injured nearly five years earlier and without many career options left in wrestling, Rude decided that he was healthy enough to make a return to the ring as a wrestler. With his comeback decided upon, the former World champion began training intensely for his imminent return to action.

Then, tragically and totally unexpectedly, Rick Rude suffered a heart attack that took his life. Certainly, when a man as young and seemingly healthy (not to mention as incredibly muscular) as Rude passes away, it raises several questions as to why. While a heart attack was the official cause of his death, it has been speculated that Rude’s prolonged use of muscle enhancing drugs may have been a major contributor to his early demise. Whatever the case, the fact remained that one of wrestling’s brightest stars was suddenly gone forever and no amount of speculation over his untimely death would bring him back. Former WWF-WCW World champion Bret Hart remembered Rude as a man far different than the one he portrayed on television for so many years. Regarding his deceased friend, Hart had this to say: “Rick was a great family man, and he loved his wife. He was one of those kind of guys who would never take his wedding ring off, he just put a white piece of tape around it when he went into the ring. He was also the kind of guy that, when you need someone to back you up, he wouldn’t flinch at all. Not for money, not for anything.”

Then, tragically and totally unexpectedly, Rick Rude suffered a heart attack that took his life. Certainly, when a man as young and seemingly healthy (not to mention as incredibly muscular) as Rude passes away, it raises several questions as to why. While a heart attack was the official cause of his death, it has been speculated that Rude’s prolonged use of muscle enhancing drugs may have been a major contributor to his early demise. Whatever the case, the fact remained that one of wrestling’s brightest stars was suddenly gone forever and no amount of speculation over his untimely death would bring him back. Former WWF-WCW World champion Bret Hart remembered Rude as a man far different than the one he portrayed on television for so many years. Regarding his deceased friend, Hart had this to say: “Rick was a great family man, and he loved his wife. He was one of those kind of guys who would never take his wedding ring off, he just put a white piece of tape around it when he went into the ring. He was also the kind of guy that, when you need someone to back you up, he wouldn’t flinch at all. Not for money, not for anything.”

“Ravishing” Rick Rude was voted Most Hated Wrestler of the Year (1992) by the readers of Pro Wrestling Illustrated and the publication ranked him #4 in its Top 500 Wrestlers edition (1992). Also in 1992, he was voted Best Heel by the readers of the Wrestling Observer Newsletter and inducted into the WWE Hall of Fame in 2017.

Richard Rood passed away on April 20, 1999 at the age of 40.

by Stephen Von Slagle

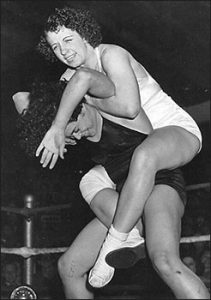

Becky Lynch. Charlotte Flair. Rhonda Rousey. Trish Stratus. Madusa Micelli. Wendy Richter. Penny Banner. The Fabulous Moolah. Cora Combs. May Young. All of them, at one time or another, rose to the top of their profession and, individually, became the biggest female stars in the sport of professional wrestling. But, whatever era they rose to stardom in, wherever there success took place, wrestling’s most successful female attractions all have one thing in common, one single factor that, ultimately, enabled them to reach the top of their profession. That common denominator, the reason they were all able to reach the pinnacle of stardom in their chosen field, is because of the trail blazed by one single pioneering woman, the Queen of the Ring, Mildred Burke.

Mildred Burke was born Mildred Bliss on August 5, 1915, in the small Midwestern town of Coffeyville, Kansas. Her childhood was somewhat chaotic, moving to different states with a great deal of frequency before landing in New Mexico. By the age of 17 she was married, relocated to back to Kansas, and hoped to forge a new path there that would lead her to a more stable life. While in Kansas City, her husband took her to a night out and the young couple attended a wrestling card, the first time Mildred had ever seen the sport. She instantly fell in love with the mat mayhem but, unfortunately, the madness she saw in the ring that night paled in comparison to what the teenage bride was experiencing at home. Sadly, her first husband would soon abandon her while she was still pregnant with his child, leaving her in a predicament that no woman should ever have to face. Still, she soldiered on, took a job as a waitress in her mother’s diner and did what she could to make the best of a very bad situation. That, ironically, is when fate intervened…

Mildred Burke was born Mildred Bliss on August 5, 1915, in the small Midwestern town of Coffeyville, Kansas. Her childhood was somewhat chaotic, moving to different states with a great deal of frequency before landing in New Mexico. By the age of 17 she was married, relocated to back to Kansas, and hoped to forge a new path there that would lead her to a more stable life. While in Kansas City, her husband took her to a night out and the young couple attended a wrestling card, the first time Mildred had ever seen the sport. She instantly fell in love with the mat mayhem but, unfortunately, the madness she saw in the ring that night paled in comparison to what the teenage bride was experiencing at home. Sadly, her first husband would soon abandon her while she was still pregnant with his child, leaving her in a predicament that no woman should ever have to face. Still, she soldiered on, took a job as a waitress in her mother’s diner and did what she could to make the best of a very bad situation. That, ironically, is when fate intervened…

When he first met Mildred Bliss in 1935, Billy Wolfe was a former wrestler and an aspiring promoter who specialized in women’s wrestling. At the time, the genre was still quite new to the public and a curiosity of sorts, simultaneously exciting men while empowering women. Sensing opportunity, Mildred implored Wolfe to train her for a career in wrestling. While she was a tiny woman at 5’2″ and 130 lbs., Bliss (who Wolfe soon renamed Mildred Burke) was in tremendous physical condition and possessed an impressive, well-muscled physique. Initially, Wolfe declined her requests, but he eventually came to see an abundance of potential in the petite teenage powerhouse and agreed to train her. Over the following months, Burke worked closely with Wolfe to develop her technique and she adapted quickly to her new profession. At the same time, Burke and Wolfe soon found themselves in a romantic relationship that would ultimately transform into a marriage which, over time, took them to the top professionally yet sunk them to the bottom personally.

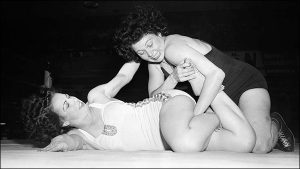

Following her formal training, the nineteen year old began her career in the carnivals, offering $25 to any man who could either defeat her or go ten minutes without being pinned by Burke. She went on to amass a record of 200-1 on the carny circuit and while many of her inter-gender victories were worked, more than a few were gained in legitimate contests. Despite her small stature, Burke was a deceivingly dangerous wrestler who possessed great physical strength and, eventually, extensive knowledge as a shooter. But, after a year or so of wrestling in the carnivals, Burke and Wolfe ran into a problem. Inter-gender wrestling was illegal in most states at that time in history, and while traditional women’s professional wrestling had been in existence for several decades, it was still very much a novelty that also faced legal roadblocks throughout many parts of the country. With the idea of leaving the carnivals and breaking into “big time” wrestling, Burke and Wolfe travelled to those areas where that goal could be achieved. Late in 1936, a determined Wolfe was successful in getting his wife booked into a program with the reigning Women’s World champion at that time, Clara Mortenson. On January 28, 1937, Mortenson dropped her title to Burke in Chattanooga, Tennessee, knowing she would soon regain the title and two weeks later, on February 11, 1937, Mortenson did just that, again in Chattanooga. A “rubber match” was booked for the following April, however, Mortenson and her handlers were not interested in losing the title to Burke again, so, when the time came, Mildred Burke defeated her opponent in a legitimate contest and once again became the Women’s World champion. But, as was often the case during this time period, many promoters who were loyal to the former titleholder simply ignored Burke’s victory and continued to bill Mortenson as champion. Undeterred, Burke, whose popularity around the country by this time was undeniable, would again have her chance at the title and on December 1, 1938, she defeated Betty Nichols in Columbus, Ohio to become a three-time Women’s World champion.

Following her formal training, the nineteen year old began her career in the carnivals, offering $25 to any man who could either defeat her or go ten minutes without being pinned by Burke. She went on to amass a record of 200-1 on the carny circuit and while many of her inter-gender victories were worked, more than a few were gained in legitimate contests. Despite her small stature, Burke was a deceivingly dangerous wrestler who possessed great physical strength and, eventually, extensive knowledge as a shooter. But, after a year or so of wrestling in the carnivals, Burke and Wolfe ran into a problem. Inter-gender wrestling was illegal in most states at that time in history, and while traditional women’s professional wrestling had been in existence for several decades, it was still very much a novelty that also faced legal roadblocks throughout many parts of the country. With the idea of leaving the carnivals and breaking into “big time” wrestling, Burke and Wolfe travelled to those areas where that goal could be achieved. Late in 1936, a determined Wolfe was successful in getting his wife booked into a program with the reigning Women’s World champion at that time, Clara Mortenson. On January 28, 1937, Mortenson dropped her title to Burke in Chattanooga, Tennessee, knowing she would soon regain the title and two weeks later, on February 11, 1937, Mortenson did just that, again in Chattanooga. A “rubber match” was booked for the following April, however, Mortenson and her handlers were not interested in losing the title to Burke again, so, when the time came, Mildred Burke defeated her opponent in a legitimate contest and once again became the Women’s World champion. But, as was often the case during this time period, many promoters who were loyal to the former titleholder simply ignored Burke’s victory and continued to bill Mortenson as champion. Undeterred, Burke, whose popularity around the country by this time was undeniable, would again have her chance at the title and on December 1, 1938, she defeated Betty Nichols in Columbus, Ohio to become a three-time Women’s World champion.

Meanwhile, as their business relationship was skyrocketing and the restrictions on women’s competition began lessening nationwide, Mildred Burke and Billy Wolfe’s marriage was quickly, irreparably falling apart. Wolfe frequently broke his marital vows, while also becoming violent with his wife on more than a few occasions and Burke soon grew to hate her husband. However, the co-dependent nature of their highly successful promoter/talent relationship prevented either from leaving the marriage. Simply put, both had too much to lose by divorcing. With the 1940s came even greater success, as women’s wrestling was experiencing a boom in popularity and Burke found herself wrestling before very large crowds and earning unprecedented sums of money, especially for a female athlete. At the same time, Wolfe was working diligently on developing a roster of new female wrestlers who he could promote and, in many cases, exploit both financially and sexually. While not a particularly admirable man in his personal life, professionally, Wolfe was driven with ambition and a desire to become nothing less than the one and only czar of women’s wrestling. To that end, he was quite successful and in 1949 Wolfe was admitted into the National Wrestling Alliance, where he served as the sole provider of female performers.

Throughout the decade of the 1940s, Burke went undefeated while defending her World championship in sold-out arenas across the country. But, in 1951, she was involved in a serious auto accident that resulted in several broken ribs, a severe neck injury and a dislocated sternoclavicular joint. While she was not required to forfeit her title, Burke was forced to take some time away from performing to allow her injuries to heal. Wolfe, however, had other plans in mind and he rushed her back into the ring so that Burke could drop her championship to his latest performer (and mistress) Nell Stewart. When Mildred informed Wolfe that she had no intention of losing her title to Stewart, she was beaten severely in the parking lot of a grocery store by Wolfe and his son. The two-on-one assault, which took place in front of Burke’s young son Joseph, resulted in more broken ribs and a beaten face for the recovering Burke. It was the final straw for the long-abused Burke and, despite the inevitable professional and financial repercussions, she filed for divorce in 1952. Being a female, Mildred Burke was unable to join the NWA, however, it was decided by the Alliance that she would be allowed to buy the exclusive rights to the title from her abusive former husband. Paying the lofty sum of $30,000, the agreement also forced Wolfe to sign a contract stating he would refrain from promoting women’s wrestling for a period of five years. Billy Wolfe, of course, had absolutely no intention of abiding by the contract and, very quickly, he began promoting his women and continued with his plans of getting the belt around Nell Stewart’s waist. When the NWA gave Wolfe the go-ahead to stage a tournament in Baltimore that was designed to crown a new women’s World champion, the actual champion, Mildred Burke, immediately sent a telegram to the Baltimore Sun, informing the newspaper that the results of the matches had already been decided upon and Stewart would be winning the tournament. Wolfe, in turn, countered by flipping his plans and having another one of his top protégés (who was also his daughter-in-law), June Byers, come out on top of the tournament. Burke tried protesting to the NWA, but by this point the Alliance had grown tired of the never ending drama between Burke and Wolfe. Rather than aid the longtime champion, its members instead decided to forego the regulation of women’s wrestling altogether.

Throughout the decade of the 1940s, Burke went undefeated while defending her World championship in sold-out arenas across the country. But, in 1951, she was involved in a serious auto accident that resulted in several broken ribs, a severe neck injury and a dislocated sternoclavicular joint. While she was not required to forfeit her title, Burke was forced to take some time away from performing to allow her injuries to heal. Wolfe, however, had other plans in mind and he rushed her back into the ring so that Burke could drop her championship to his latest performer (and mistress) Nell Stewart. When Mildred informed Wolfe that she had no intention of losing her title to Stewart, she was beaten severely in the parking lot of a grocery store by Wolfe and his son. The two-on-one assault, which took place in front of Burke’s young son Joseph, resulted in more broken ribs and a beaten face for the recovering Burke. It was the final straw for the long-abused Burke and, despite the inevitable professional and financial repercussions, she filed for divorce in 1952. Being a female, Mildred Burke was unable to join the NWA, however, it was decided by the Alliance that she would be allowed to buy the exclusive rights to the title from her abusive former husband. Paying the lofty sum of $30,000, the agreement also forced Wolfe to sign a contract stating he would refrain from promoting women’s wrestling for a period of five years. Billy Wolfe, of course, had absolutely no intention of abiding by the contract and, very quickly, he began promoting his women and continued with his plans of getting the belt around Nell Stewart’s waist. When the NWA gave Wolfe the go-ahead to stage a tournament in Baltimore that was designed to crown a new women’s World champion, the actual champion, Mildred Burke, immediately sent a telegram to the Baltimore Sun, informing the newspaper that the results of the matches had already been decided upon and Stewart would be winning the tournament. Wolfe, in turn, countered by flipping his plans and having another one of his top protégés (who was also his daughter-in-law), June Byers, come out on top of the tournament. Burke tried protesting to the NWA, but by this point the Alliance had grown tired of the never ending drama between Burke and Wolfe. Rather than aid the longtime champion, its members instead decided to forego the regulation of women’s wrestling altogether.

Eventually, Wolfe was able to secure a title match for June Byers and he was determined to make sure Burke did not walk out of the ring with her championship belt. He was successful in this goal and on August 20, 1954, in Atlanta, Georgia, Mildred Burke’s sixteen years as the Women’s World champion came to an end in one of the most controversial matches in the history of women’s wrestling. The grudge match, which turned out to be a complete shoot, was scheduled to be a two-of-three falls bout. However, after Burke lost the first fall, Wolfe’s hand-picked referee declared that the match was over and raised Byers’ arm in victory. Since June Byers had only won one fall, Burke felt her title was safe. She was wrong. Billy Wolfe made sure that the local press touted Byers’ title victory and successfully petitioned the NWA to recognize Byers as the new champion, both of which hurt Burke’s claim to the title tremendously. While a handful of matchmakers remained loyal to her, Mildred Burke soon found herself ostracized by the majority of U.S. promoters, ensuring that she was unable to find steady work.

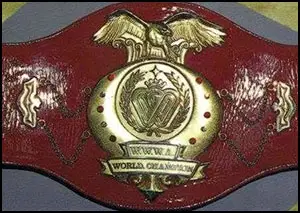

Having seen the writing on the wall, Burke created the Los Angeles-based World Women’s Wrestling Association just prior to her showdown with June Byers and, following the controversial loss, she continued to train new female wrestlers while overseeing the WWWA and serving as its World champion. Viewed as an “outlaw” promotion by the NWA members, Burke’s WWWA was forced to stage its own cards and create its own roster of talent. In 1954, she left the U.S. for a tour of Japan, billing herself as the undefeated World champion. Burke’s matches there proved to be very successful with the Japanese public, planting the seeds for the future of women’s wrestling in that country and leading to the creation of the All Japan Women’s Pro-Wrestling Association.

Having seen the writing on the wall, Burke created the Los Angeles-based World Women’s Wrestling Association just prior to her showdown with June Byers and, following the controversial loss, she continued to train new female wrestlers while overseeing the WWWA and serving as its World champion. Viewed as an “outlaw” promotion by the NWA members, Burke’s WWWA was forced to stage its own cards and create its own roster of talent. In 1954, she left the U.S. for a tour of Japan, billing herself as the undefeated World champion. Burke’s matches there proved to be very successful with the Japanese public, planting the seeds for the future of women’s wrestling in that country and leading to the creation of the All Japan Women’s Pro-Wrestling Association.

In addition to pioneering women’s wrestling in the U.S. and Japan, Burke also introduced the genre of the sport to countries such as Canada, Mexico and Cuba. In 1956, Burke wrestled the final match of her storied career in Cuba and then vacated her championship. Subsequently, the WWWA World championship was revived in 1970 when All Japan Women’s Wrestling bought the rights to Burke’s prestigious World title belt. The popular Japanese promotion would later create the WWWA World tag team title in 1971 and the WWWA All Pacific championship in 1977.