ssa

by Stephen Von Slagle

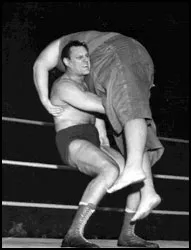

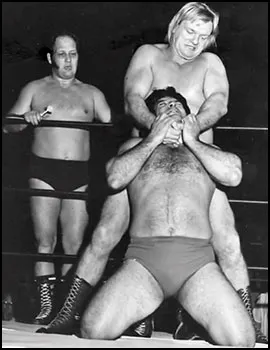

Perhaps no other wrestler is more responsible for influencing the genre of hardcore wrestling than the one and only Arabian madman known as The Sheik. Famous worldwide for being the most unpredictable, violent, bloodthirsty competitor in pro wrestling, The Sheik was “hardcore” decades before anyone had come up with a term to describe his style. Simply put, if The Sheik was wrestling, fans of the day knew, without any question, that they were going to see a bloodbath. His maniacal persona, not to mention his penchant for participating in overly gruesome, ultra-violent matches, set a standard that hardcore wrestlers are still trying to equal, some 70 years after his debut.

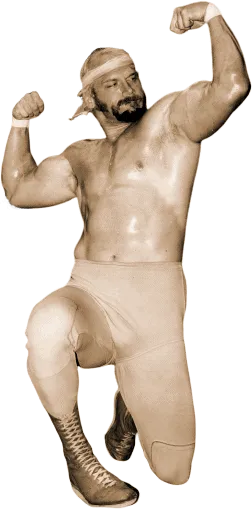

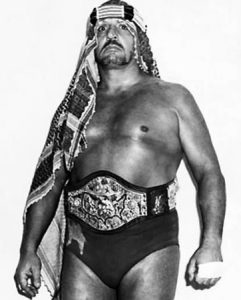

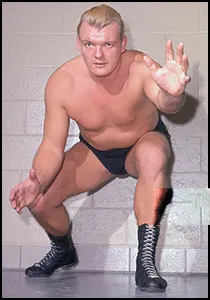

Edward Farhat was born on June 7, 1926, the son of Lebanese parents. After attending Michigan State University, he began his career wrestling for Fred Kohler’s Chicago-based promotion in the early 1950s. Known as the Sheik of Araby, the privileged son of a wealthy aristocratic Middle Eastern family, he was one of the great early “TV wrestling” villains on the Dumont network. At the time, the young Farhat was trim, in shape and, with his controversial handler Abdullah Farouk (Ernie Roth), very good at getting under the fans’ skin. Adorned in his traditional Arabian headdress, wearing his famous pointed-tip wrestling boots and carrying a ceremonial sword to the ring, his pre-match ritual of laying a Persian prayer rug in the ring and bowing to Allah was a controversial heat-generator. From the start, The Sheik was truly a unique wrestling character who quickly established himself as a top box office draw for promoters of the day. There were many reasons for The Sheik’s success, none of which, admittedly, had anything to do with actual technical wrestling skills, of which he displayed virtually none. Obviously, his infamous bloodlust and pencil-wielding penchant for gore and brutality were calling cards that fans everywhere were well aware of. Additionally, he originated the “fire throwing” gimmick, which was later copied by countless others, and he was the first wrestler to bring a live snake with him to the ring. But, most importantly, The Sheik literally never broke character, truly living his gimmick and keeping a legitimate air of mystery about him at all times.

Edward Farhat was born on June 7, 1926, the son of Lebanese parents. After attending Michigan State University, he began his career wrestling for Fred Kohler’s Chicago-based promotion in the early 1950s. Known as the Sheik of Araby, the privileged son of a wealthy aristocratic Middle Eastern family, he was one of the great early “TV wrestling” villains on the Dumont network. At the time, the young Farhat was trim, in shape and, with his controversial handler Abdullah Farouk (Ernie Roth), very good at getting under the fans’ skin. Adorned in his traditional Arabian headdress, wearing his famous pointed-tip wrestling boots and carrying a ceremonial sword to the ring, his pre-match ritual of laying a Persian prayer rug in the ring and bowing to Allah was a controversial heat-generator. From the start, The Sheik was truly a unique wrestling character who quickly established himself as a top box office draw for promoters of the day. There were many reasons for The Sheik’s success, none of which, admittedly, had anything to do with actual technical wrestling skills, of which he displayed virtually none. Obviously, his infamous bloodlust and pencil-wielding penchant for gore and brutality were calling cards that fans everywhere were well aware of. Additionally, he originated the “fire throwing” gimmick, which was later copied by countless others, and he was the first wrestler to bring a live snake with him to the ring. But, most importantly, The Sheik literally never broke character, truly living his gimmick and keeping a legitimate air of mystery about him at all times.

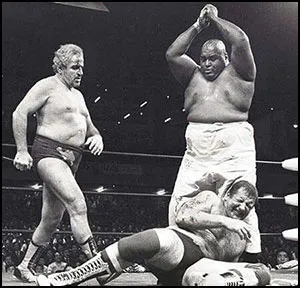

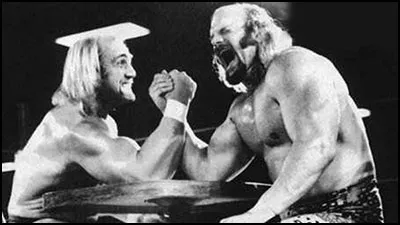

Another factor in The Sheik’s immense fame and notoriety came from the fact that he wrestled in territories covering the entire nation at a time when wrestling was very regionalized. The Sheik was also a true world traveler and he performed in nearly every country that had a following for pro wrestling. His wild, gory battles with archrival Bobo Brazil, as well as Terry Funk, Antonino Rocca, Johnny Valentine, Bruno Sammartino, Dick the Bruiser, Mark Lewin, Fred Blassie and Harley Race were the stuff of legend, not to mention box office gold. The Sheik also had a bizarre and bloody decades-long love/hate relationship with the only man who could ever lay serious claim to his title as the “Most Vicious Man In Wrestling,” Abdullah the Butcher. With Abdullah’s fork in hand, and The Sheik with his pencil, the two wrestling madmen ripped and tore into each other in arenas around the world with a furor and vengeance nearly unparalleled in the history of wrestling. The point of contention was simple; who was the more violent, more insane, more extreme wrestler between the two. In a strange, twisted sort of way, the Abdullah vs. Sheik bouts were battles of honor, respect and pride…with a truckload of foreign objects and many gallons of blood poured in for good measure. Additionally, when paired together, which was a semi-frequent occurrence over the years, the team of The Sheik and Abdullah was a legitimately frightening duo for whomever was unlucky enough to be facing them.

Another factor in The Sheik’s immense fame and notoriety came from the fact that he wrestled in territories covering the entire nation at a time when wrestling was very regionalized. The Sheik was also a true world traveler and he performed in nearly every country that had a following for pro wrestling. His wild, gory battles with archrival Bobo Brazil, as well as Terry Funk, Antonino Rocca, Johnny Valentine, Bruno Sammartino, Dick the Bruiser, Mark Lewin, Fred Blassie and Harley Race were the stuff of legend, not to mention box office gold. The Sheik also had a bizarre and bloody decades-long love/hate relationship with the only man who could ever lay serious claim to his title as the “Most Vicious Man In Wrestling,” Abdullah the Butcher. With Abdullah’s fork in hand, and The Sheik with his pencil, the two wrestling madmen ripped and tore into each other in arenas around the world with a furor and vengeance nearly unparalleled in the history of wrestling. The point of contention was simple; who was the more violent, more insane, more extreme wrestler between the two. In a strange, twisted sort of way, the Abdullah vs. Sheik bouts were battles of honor, respect and pride…with a truckload of foreign objects and many gallons of blood poured in for good measure. Additionally, when paired together, which was a semi-frequent occurrence over the years, the team of The Sheik and Abdullah was a legitimately frightening duo for whomever was unlucky enough to be facing them.

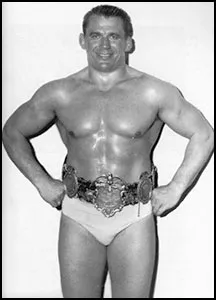

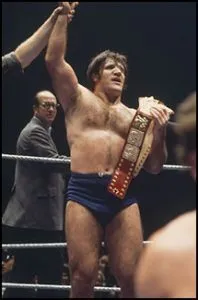

Despite the fact that bloodletting, not acquiring championships, was his primary goal as a wrestler, The Sheik was nevertheless a winner and he collected more than his fair share of title belts. He was known primarily as the perennial United States Heavyweight champion (Detroit version) by virtue of his twelve separate U.S. title victories, which The Sheik acquired between 1965-1980. However, he also wore the WWWF, Central States, Maple Leaf Wrestling and I.C.W. versions of United States title as well. In 1969, he defeated archrival Bobo Brazil for the NWA Americas Heavyweight title, only to lose it to another of his many bitter rivals, “Classy” Fred Blassie. The Sheik regained the strap from Blassie, but held it for a relatively short time before losing to the legendary luchador, Mil Mascaras. Internationally, he defeated Seiji Sakaguchi for the prestigious United National Heavyweight championship on September 6, 1972, in Tokyo.

In addition to his overwhelming success wrestling in promotions all across the globe, Ed Farhat developed a healthy, profitable regional NWA territory in Michigan. With Detroit as its base of operations, Farhat’s “Big Time Wrestling” TV program and the group’s live events (which also covered parts of Ohio and Ontario) were a major part of the NWA’s territorial structure between 1964-1980. During the early 1970s, Detroit was unquestionably one of the top territories in the NWA, and The Sheik’s promotion was the subject of the classic quasi-documentary, “I Like To Hurt People.” In addition to bringing in top talent to the promotion, Farhat also had a hand in training and developing many of his own young performers, including future superstars like his nephew Sabu, Rob Van Dam, and Scott Steiner, as well as young independent stars like “Machine Gun” Mike Kelly.

In addition to his overwhelming success wrestling in promotions all across the globe, Ed Farhat developed a healthy, profitable regional NWA territory in Michigan. With Detroit as its base of operations, Farhat’s “Big Time Wrestling” TV program and the group’s live events (which also covered parts of Ohio and Ontario) were a major part of the NWA’s territorial structure between 1964-1980. During the early 1970s, Detroit was unquestionably one of the top territories in the NWA, and The Sheik’s promotion was the subject of the classic quasi-documentary, “I Like To Hurt People.” In addition to bringing in top talent to the promotion, Farhat also had a hand in training and developing many of his own young performers, including future superstars like his nephew Sabu, Rob Van Dam, and Scott Steiner, as well as young independent stars like “Machine Gun” Mike Kelly.

However, despite its many years of success, as the owner, booker and featured star of the promotion, Farhat’s group eventually became stale, with repetitive booking burning-out its once large audience. Additionally, a frequent history of false advertising and no-shows on major cards certainly did not help the situation. Meanwhile, the fiercely independent Farhat alienated many of his fellow promoters within the NWA, causing ongoing problems between himself and the Alliance during the late 1970s. In 1980, following several years of declining business and the crippling loss of its television outlet, Big Time Wrestling folded. However, despite the loss of his promotion and even as he passed the age of 50, then 60, and reached 70, The Sheik continued to be a force within professional wrestling. While competing in Atushi Onita’s ultra-violent Frontier Martial Arts promotion in 1992, The Sheik defeated Onita in Tokyo for the F.M.W. Martial Arts championship at the age of 66. He also appeared in ECW (then known as Eastern Championship Wrestling) briefly in 1994. Then, in 1998, forty-nine years after he first began his career, The Sheik wrestled his final match in Japan at the age of 72.

However, despite its many years of success, as the owner, booker and featured star of the promotion, Farhat’s group eventually became stale, with repetitive booking burning-out its once large audience. Additionally, a frequent history of false advertising and no-shows on major cards certainly did not help the situation. Meanwhile, the fiercely independent Farhat alienated many of his fellow promoters within the NWA, causing ongoing problems between himself and the Alliance during the late 1970s. In 1980, following several years of declining business and the crippling loss of its television outlet, Big Time Wrestling folded. However, despite the loss of his promotion and even as he passed the age of 50, then 60, and reached 70, The Sheik continued to be a force within professional wrestling. While competing in Atushi Onita’s ultra-violent Frontier Martial Arts promotion in 1992, The Sheik defeated Onita in Tokyo for the F.M.W. Martial Arts championship at the age of 66. He also appeared in ECW (then known as Eastern Championship Wrestling) briefly in 1994. Then, in 1998, forty-nine years after he first began his career, The Sheik wrestled his final match in Japan at the age of 72.

During his five decades in professional wrestling, The Sheik not only created a “Mad Arab” character that has been emulated many times over, but he also set a standard of violence and mayhem inside the ring that few have ever been able to match. Consequently, he will forever go down in history as one of the most important wrestling figures of the late twentieth century. As such, The Sheik is a member of the Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Fame (1996), the WWE Hall of Fame (2007), the NWA Hall of Fame (2010) and the Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame and Museum (2011).

During his five decades in professional wrestling, The Sheik not only created a “Mad Arab” character that has been emulated many times over, but he also set a standard of violence and mayhem inside the ring that few have ever been able to match. Consequently, he will forever go down in history as one of the most important wrestling figures of the late twentieth century. As such, The Sheik is a member of the Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Fame (1996), the WWE Hall of Fame (2007), the NWA Hall of Fame (2010) and the Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame and Museum (2011).

On January 18, 2003, Edward “The Sheik” Farhat passed away due to heart failure at the age of 76.

by Stephen Von Slagle

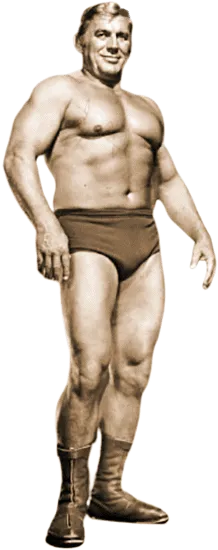

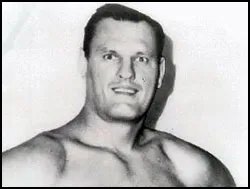

Edouard Carpentier, who was known worldwide as “The Flying Frenchman,” began his legendary career in 1952 in his native France. His amateur skills translated well to the pro rings, but it was Carpentier’s unique acrobatic style inside the squared circle that helped set himself apart from the other wrestlers of the day, quickly launching himself to the upper-level of the profession. Known for always being in top physical condition, Carpentier proved himself to be one of wrestling’s biggest box-office draws and the profound impact he made as a World champion in three separate promotions cannot be questioned. During his prime, which lasted for well over a decade, Edouard Carpentier was truly among wrestling’s trend-setting elite and he unquestionably helped shape professional wrestling into what it is today.

Edouard Carpentier was born Edouard Weiczorkiewicz on July 17, 1926 in Roanne, Loire, France. While still a teenager, he joined the French resistance and fought against the Germans during World War II. Following the war, he was awarded two medals of honor for his service by the French government. In addition to training in the art of Greco-Roman wrestling, Weiczorkiewicz also pursued the sport of gymnastics, and it was as a gymnast that he truly excelled, to the point where he earned a spot as an alternate on the 1948 French Olympic squad. He was discovered while competing in France by NWA promoters Eddie Quinn and Frank Tunney, who were impressed by his acrobatic ringwork, which was very similar to Antonino Rocca in style. The Canadian promoters felt Weiczorkiewicz could be a major success back in North America and asked him to compete for them in North America. Weiczorkiewicz agreed, moved to Montreal in 1956, and soon became a Canadian citizen. Eddie Quinn gave Weiczorkiewicz a new ring name and persona (after the famous boxer Georges Carpentier, to whom Edouard now claimed a family ancestory) and his unique talents quickly translated into championship gold. A top draw for Quinn’s Montreal-based International Wrestling Association promotion, he defeated “Killer” Kowalski for the IWA World championship in 1957. Kowalski, who was already one of the sports’ biggest names, would turn out to be one of Carpentier’s greatest foes and on September 21, 1960 he again defeated The Killer for the IWA championship, holding the title for nearly a year before losing to another one of his major rivals, Hans Schmidt, in July of 1961. All total, Carpentier won the IWA World title five times between 1957-1967, defeating legends like Kowalski, Schmidt, and The Sheik for the prestigious IWA championship.

Edouard Carpentier was born Edouard Weiczorkiewicz on July 17, 1926 in Roanne, Loire, France. While still a teenager, he joined the French resistance and fought against the Germans during World War II. Following the war, he was awarded two medals of honor for his service by the French government. In addition to training in the art of Greco-Roman wrestling, Weiczorkiewicz also pursued the sport of gymnastics, and it was as a gymnast that he truly excelled, to the point where he earned a spot as an alternate on the 1948 French Olympic squad. He was discovered while competing in France by NWA promoters Eddie Quinn and Frank Tunney, who were impressed by his acrobatic ringwork, which was very similar to Antonino Rocca in style. The Canadian promoters felt Weiczorkiewicz could be a major success back in North America and asked him to compete for them in North America. Weiczorkiewicz agreed, moved to Montreal in 1956, and soon became a Canadian citizen. Eddie Quinn gave Weiczorkiewicz a new ring name and persona (after the famous boxer Georges Carpentier, to whom Edouard now claimed a family ancestory) and his unique talents quickly translated into championship gold. A top draw for Quinn’s Montreal-based International Wrestling Association promotion, he defeated “Killer” Kowalski for the IWA World championship in 1957. Kowalski, who was already one of the sports’ biggest names, would turn out to be one of Carpentier’s greatest foes and on September 21, 1960 he again defeated The Killer for the IWA championship, holding the title for nearly a year before losing to another one of his major rivals, Hans Schmidt, in July of 1961. All total, Carpentier won the IWA World title five times between 1957-1967, defeating legends like Kowalski, Schmidt, and The Sheik for the prestigious IWA championship.

As important as the IWA title was, winning the true World championship, the NWA World Heavyweight title, was the real goal for the majority of wrestlers during this era. Carpentier seemed to have achieved that historic milestone on June 14, 1957 in Chicago when he defeated NWA champion Lou Thesz via DQ. After splitting the first two falls, Thesz did not come to the ring for the third fall, claiming an injured back, and was disqualified. Since a title cannot change via DQ, the NWA continued to recognize Thesz as World champion. Meanwhile, several powerful promoters supported Carpentier’s claim to the championship as well. And, ultimately, that was the real goal of the match…to create two titleholders so that NWA promoters could have access to the World championship (and, more specifically, the substantial revenue generated by its defense) while Thesz was out of the country on a two-month tour of Asia. Thus, in a somewhat confusing series of events, Carpentier was recognized as NWA champion for 71 days and defended his claim to the World title in arenas around the country (in particular, Chicago, Los Angeles, parts of the Midwest and Canada) while Thesz was simultaneously doing the same thing, just on the other side of the planet. To further add to the confusion, Carpentier’s victory and title reign were soon erased from history by the National Wrestling Alliance after a falling out between Eddie Quinn and NWA President Sam Muchnick. Due in large part to the controversy created by the convoluted NWA title situation, Carpentier’s disputed victory over Thesz would be used to establish non-NWA, regional world title lineages in Boston, Omaha and Los Angeles.

As important as the IWA title was, winning the true World championship, the NWA World Heavyweight title, was the real goal for the majority of wrestlers during this era. Carpentier seemed to have achieved that historic milestone on June 14, 1957 in Chicago when he defeated NWA champion Lou Thesz via DQ. After splitting the first two falls, Thesz did not come to the ring for the third fall, claiming an injured back, and was disqualified. Since a title cannot change via DQ, the NWA continued to recognize Thesz as World champion. Meanwhile, several powerful promoters supported Carpentier’s claim to the championship as well. And, ultimately, that was the real goal of the match…to create two titleholders so that NWA promoters could have access to the World championship (and, more specifically, the substantial revenue generated by its defense) while Thesz was out of the country on a two-month tour of Asia. Thus, in a somewhat confusing series of events, Carpentier was recognized as NWA champion for 71 days and defended his claim to the World title in arenas around the country (in particular, Chicago, Los Angeles, parts of the Midwest and Canada) while Thesz was simultaneously doing the same thing, just on the other side of the planet. To further add to the confusion, Carpentier’s victory and title reign were soon erased from history by the National Wrestling Alliance after a falling out between Eddie Quinn and NWA President Sam Muchnick. Due in large part to the controversy created by the convoluted NWA title situation, Carpentier’s disputed victory over Thesz would be used to establish non-NWA, regional world title lineages in Boston, Omaha and Los Angeles.

One of the most sought-after attractions in the business, Carpentier played a major part in the creation of Verne Gagne’s AWA World championship, lending credibility to Gagne’s World title claim when he lost to the Minnesotan on August 9, 1958. In later years, Carpentier would enjoy several successful stints in the American Wrestling Association. Then, in December of 1960, Carpentier was awarded the newly-created WWA World championship, with L.A. promoters Jules Strongbow, Cal Eaton & Gene Labell citing Carpentier’s “rightful” NWA title claim as the reason for awarding him the new belt. With Carpentier serving as the inaugural titleholder, the Los Angeles-based WWA championship quickly became a respected, prestigious (albeit regional) World title. One of “The Flying Frenchman’s” major rivals, “Classy” Fred Blassie, eventually defeated him in 1961, ending Carpentier’s WWA title reign. Two years later, Carpentier regained the WWA World title, but was again defeated by the villainous Blassie on January 30, 1964.

One of the most sought-after attractions in the business, Carpentier played a major part in the creation of Verne Gagne’s AWA World championship, lending credibility to Gagne’s World title claim when he lost to the Minnesotan on August 9, 1958. In later years, Carpentier would enjoy several successful stints in the American Wrestling Association. Then, in December of 1960, Carpentier was awarded the newly-created WWA World championship, with L.A. promoters Jules Strongbow, Cal Eaton & Gene Labell citing Carpentier’s “rightful” NWA title claim as the reason for awarding him the new belt. With Carpentier serving as the inaugural titleholder, the Los Angeles-based WWA championship quickly became a respected, prestigious (albeit regional) World title. One of “The Flying Frenchman’s” major rivals, “Classy” Fred Blassie, eventually defeated him in 1961, ending Carpentier’s WWA title reign. Two years later, Carpentier regained the WWA World title, but was again defeated by the villainous Blassie on January 30, 1964.

From November of 1971 through June of 1973, Carpentier won the Montreal-based Grand Prix Heavyweight title on four occasions, defeating longtime rivals Kowalski and “Mad Dog” Vachon for the prestigious yet short-lived championship. On July 14, 1973 he and former WWWF champion Bruno Sammartino created a dream-team which won the Grand Prix Tag Team title and, on December 25, 1974, Carpentier defeated West Coast legend John Tolos to win the NWA Americas Heavyweight championship. While Americas champion, he also engaged in an intense feud with rookie sensation Greg Valentine, son of Carpentier’s former bitter rival, Johnny Valentine. The young “Hammer” proved he was a force to be reckoned with, as he defeated the veteran Frenchman for the Americas title. However, the experienced Carpentier regained the title a month later, on March 14, 1975 in Los Angeles. In addition to his multiple World titles, Carpentier also won numerous regional and tag team championships during his lengthy career, essentially becoming a champion of some form in every territory in which he ever wrestled.

From November of 1971 through June of 1973, Carpentier won the Montreal-based Grand Prix Heavyweight title on four occasions, defeating longtime rivals Kowalski and “Mad Dog” Vachon for the prestigious yet short-lived championship. On July 14, 1973 he and former WWWF champion Bruno Sammartino created a dream-team which won the Grand Prix Tag Team title and, on December 25, 1974, Carpentier defeated West Coast legend John Tolos to win the NWA Americas Heavyweight championship. While Americas champion, he also engaged in an intense feud with rookie sensation Greg Valentine, son of Carpentier’s former bitter rival, Johnny Valentine. The young “Hammer” proved he was a force to be reckoned with, as he defeated the veteran Frenchman for the Americas title. However, the experienced Carpentier regained the title a month later, on March 14, 1975 in Los Angeles. In addition to his multiple World titles, Carpentier also won numerous regional and tag team championships during his lengthy career, essentially becoming a champion of some form in every territory in which he ever wrestled.

The popular Frenchman engaged in long-lasting, intense feuds with the likes Kowalski, Schmidt, Thesz and Blassie, as well as Johnny & Greg Valentine, Abdullah the Butcher, The Sheik, Maurice “Mad Dog” Vachon, John Tolos, and many other true legends of the squared circle. Although his opponents were often among the most vicious and dastardly wrestlers in the business, Carpentier was always known as a man who stuck to the rules and still came out on top. Meanwhile, his combination of technical skill and creativity inside the ring never failed to attract a crowd or thrill his many fans.

The popular Frenchman engaged in long-lasting, intense feuds with the likes Kowalski, Schmidt, Thesz and Blassie, as well as Johnny & Greg Valentine, Abdullah the Butcher, The Sheik, Maurice “Mad Dog” Vachon, John Tolos, and many other true legends of the squared circle. Although his opponents were often among the most vicious and dastardly wrestlers in the business, Carpentier was always known as a man who stuck to the rules and still came out on top. Meanwhile, his combination of technical skill and creativity inside the ring never failed to attract a crowd or thrill his many fans.

“The Flying Frenchman” is a member of the Stampede Wrestling Hall of Fame (1995), the Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Fame (1997), and the Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame and Museum (2010)

On October 30, 2010, Edouard “Edouard Carpentier” Weiczorkiewicz died of a heart attack at his home in Montreal. He was 84 years old.

by Stephen Von Slagle

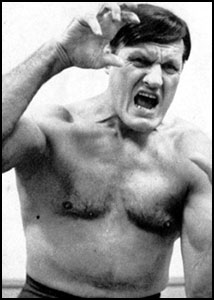

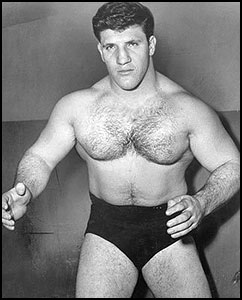

During the “Golden Age” of professional wrestling immediately following World War II, there were many famous wrestling heroes and villains that were known all across the country, due primarily to the fact that wrestling was an enormous part of the early development of television. At a time when a broadcast day for the networks lasted less than 12 hours, there was still hour after hour of professional wrestling featured on the new entertainment medium. Pro wrestling was experiencing a huge boom in popularity and certain names stuck out in the minds of wrestling fans and the public at large. “Killer” Kowalski, the hulking Polish monster of the mat, was unquestionably one of the most famous of them all.

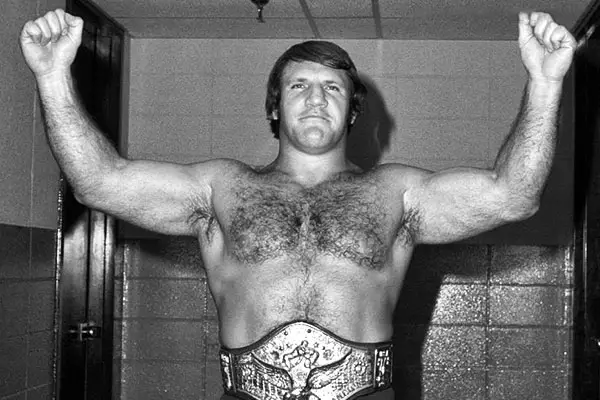

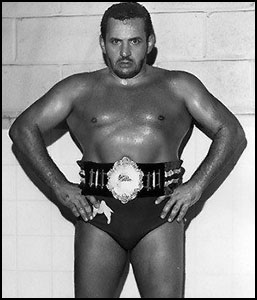

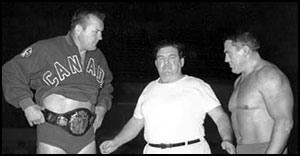

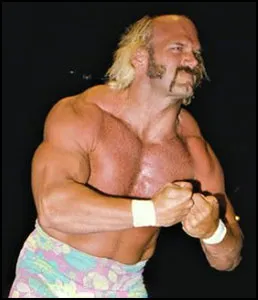

Wladek “Killer” Kowalski was born Edward Władysław Spulnik on October 13, 1926 in Windsor, Ontario. He was discovered and trained by promoter Bert Ruby, who saw a future superstar (and, no doubt, many dollar bills) in the massive 22 year-old. Standing 6’6″ and weighing nearly 300 lbs., it wasn’t difficult to understand what attracted Ruby to Spulnik and he soon made his professional debut in 1948, originally competing in the Central States promotion as Tarzan Kowalski. He also used the ring name Hercules Kowalski before settling on the name that would make him famous, “Killer” Kowalski. After appearing on Fred Kohler’s nationally broadcast Chicago-based wrestling program, Kowalski caught the eye of Sam Muchnick and other members of the NWA’s hierarchy, all of whom were interested in employing the young giant. Standing head and shoulders above his competition, literally, Kowalski quickly became feared as one of the most vicious and unrelenting villains the sport had ever known. One of his earliest championships was the prestigious NWA Texas Heavyweight title, which he won on August 22, 1950 when he defeated “Nature Boy” Buddy Rogers in Dallas, Texas. On a roll, the Polish wrecking machine also won the Texas Tag Team title on December 11, 1950, single-handedly defeating reigning champions Duke Keomuka & Danny Savich in a handicap title match. In 1951, he won the Central States Heavyweight title, defeating former three-time NWA champion “Wild” Bill Longson in Kansas City and instantly ruled the Midwest as a result.

Wladek “Killer” Kowalski was born Edward Władysław Spulnik on October 13, 1926 in Windsor, Ontario. He was discovered and trained by promoter Bert Ruby, who saw a future superstar (and, no doubt, many dollar bills) in the massive 22 year-old. Standing 6’6″ and weighing nearly 300 lbs., it wasn’t difficult to understand what attracted Ruby to Spulnik and he soon made his professional debut in 1948, originally competing in the Central States promotion as Tarzan Kowalski. He also used the ring name Hercules Kowalski before settling on the name that would make him famous, “Killer” Kowalski. After appearing on Fred Kohler’s nationally broadcast Chicago-based wrestling program, Kowalski caught the eye of Sam Muchnick and other members of the NWA’s hierarchy, all of whom were interested in employing the young giant. Standing head and shoulders above his competition, literally, Kowalski quickly became feared as one of the most vicious and unrelenting villains the sport had ever known. One of his earliest championships was the prestigious NWA Texas Heavyweight title, which he won on August 22, 1950 when he defeated “Nature Boy” Buddy Rogers in Dallas, Texas. On a roll, the Polish wrecking machine also won the Texas Tag Team title on December 11, 1950, single-handedly defeating reigning champions Duke Keomuka & Danny Savich in a handicap title match. In 1951, he won the Central States Heavyweight title, defeating former three-time NWA champion “Wild” Bill Longson in Kansas City and instantly ruled the Midwest as a result.

But The Killer, who was incredibly agile for such a huge man, was also feared in the tag team ranks. Early on in his career he formed a highly successful and virtually undefeatable team with the equally huge 6′ 6″, 270 lbs. German powerhouse Hans Herman and the duo was among the era’s tag team elite, winning the NWA Pacific Coast Tag title in 1951, among other championships. However, “Killer” Kowalski had some of his greatest success when he returned home to Canada (Montreal, in particular) and became a genuine superstar who was hated like none other. He wore the regionally prestigious IWA World Heavyweight championship eight different times between 1952-1962, defeating wrestlers the caliber of Verne Gagne, Edouard Carpentier, Don Leo Jonathon, Pat O`Connor, and others for Canada’s top championship. It was in Montreal where he also cemented his reputation as wrestling’s most notorious villain when, on October 15, 1952, Kowalski tore off a portion of Yukon Eric’s ear while executing a knee drop. Of course, in reality, the injury was accidental, however, the press and notoriety that followed forever fortified Kowalski’s reputation among fans as being the most ruthless, bloodthirsty villain in the sport.

With his notorious name and reputation secured throughout The Great White North, Kowalski ventured back to America, this time to New York City and the World Wide Wrestling Federation. Once there, he established himself as the most violent wrestler on the East Coast, giving every “fan favorite” wrestler, including WWWF kingpin Bruno Sammartino, some of the most brutal beatings that fans along the eastern seaboard had ever seen. Along with the then-hated Gorilla Monsoon, he won the WWWF United States Tag Team title in November of 1963 in Washington, D.C. by defeating the team of Skull Murphy and Brute Bernard. After his impressive first run in the WWWF, Kowalski continued his never-ending travels, and eventually landed in the NWA’s Hawaiian territory, where he won the promotion’s version of the U.S. Heavyweight title by defeating Curtis Iaukea on November 3, 1965.

Not long after competing in the Hawaiian territory, Kowalski made the decision to switch to a vegetarian diet and lifestyle, which he continued for the remainder of his years. Following his retirement, Kowalski became a frequent public speaker on the virtues and benefits of vegetarianism. And, while the change in lifestyle did visually affect his once-mammoth, heavily-muscled physique, Kowalski’s legendary stamina and endurance remained unchanged.

With the new decade of the 1970s, “Killer” Kowalski continued to travel from territory to territory, with success always following. In 1970, he won the Texas Brass Knuckles championship by defeating the rugged Johnny Valentine. He also traveled to California, winning the prestigious NWA Americas Heavyweight title on January 31, 1972 by defeating Los Angeles wrestling legend John Tolos. During this time period, he also won the NWA America’s Tag Team title with Kinji Shibuya. From there, Kowalski returned to the northeast and the World Wide Wrestling Federation where he donned a mask and teamed with John Studd as the Masked Executioners. With Lou Albano serving as their manager, The Executioners defeated Tony Parisi and Louis Cerdan to win the WWWF Tag Team championship on May 11, 1976 in Philadelphia and the two colossal masked men went on to hold the straps for over five months.

Following his retirement from active competition in 1977, Kowalski continued to be involved in the sport as a trainer and his Massachusetts-based wrestling academy was responsible for starting and/or advancing the careers of dozens of future wrestling superstars. Of course, his two most famous students, Triple H and Chyna, went on to the very top of the profession. But, Kowalski also had a hand in training many other major names including, among others, Luna Vachon, Aron Stevens, The Eliminators (Saturn and Kronus), April Hunter, Chris Nowinski and Fandango.

Following his retirement from active competition in 1977, Kowalski continued to be involved in the sport as a trainer and his Massachusetts-based wrestling academy was responsible for starting and/or advancing the careers of dozens of future wrestling superstars. Of course, his two most famous students, Triple H and Chyna, went on to the very top of the profession. But, Kowalski also had a hand in training many other major names including, among others, Luna Vachon, Aron Stevens, The Eliminators (Saturn and Kronus), April Hunter, Chris Nowinski and Fandango.

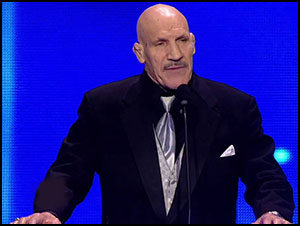

“Killer” Kowalski was inducted into the WWE Hall of Fame in 1996, followed by the Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Fame, also in 1996, as well as the National Polish-American Sports Hall of Fame in 2007. Kowalski was also honored with the Cauliflower Alley Club’s prestigious “Iron” Mike Mazurki Award in 2002.

“Killer” Kowalski was inducted into the WWE Hall of Fame in 1996, followed by the Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Fame, also in 1996, as well as the National Polish-American Sports Hall of Fame in 2007. Kowalski was also honored with the Cauliflower Alley Club’s prestigious “Iron” Mike Mazurki Award in 2002.

On August 8, 2008, Wladek “Killer Kowalski” Spulnik suffered a heart attack and subsequently passed away on August 30, 2008 at the age of 81.

by Stephen Von Slagle

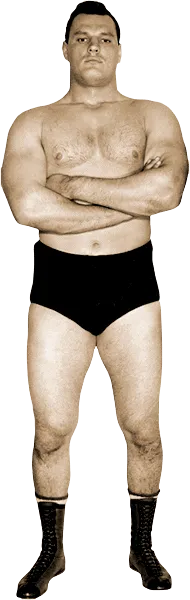

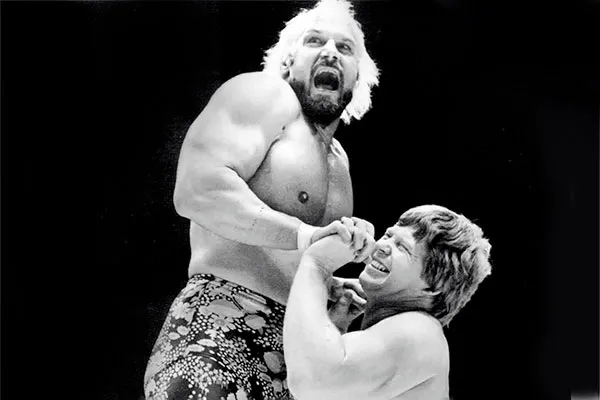

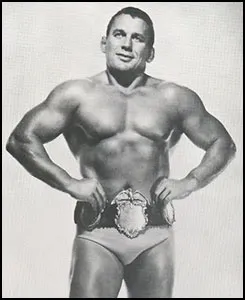

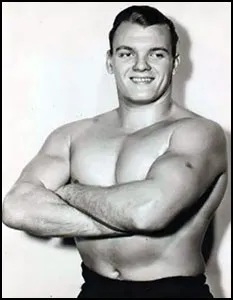

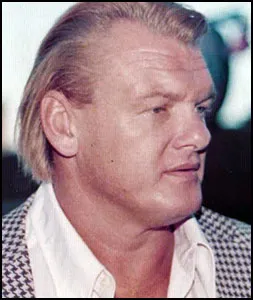

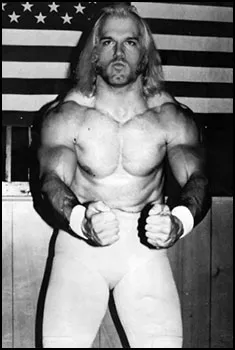

Professional wrestling’s “Golden Age” of the late-1940s through the late-1950s produced a number of legendary grapplers who, by appearing on the newly-created medium of television, became household names during that era. Johnny Valentine was one of those “Golden Age” greats, one of the toughest, most physical villains in the history of wrestling as well as one of its most prolific champions. As a performer, few could match Valentine’s ability to get his story across to the fans and at 6`4″ and 250 lbs., with bleached blond hair, Valentine perpetuated a look and persona that is still part of wrestling to this day. A testament to his talent and staying power, Valentine was a top performer beginning in the late-1940s until the end of his career in the mid-1970s, proving that his straight-forward, no-nonsense style of wrestling could be successful in any time period. During his prime, he was among the most famous wrestlers in the country and Valentine became a role model for many wrestlers to come.

Johnny Valentine was born John Wisniski on September 22, 1928 in Hobart, Washington and originally he trained as a boxer before making the switch to wrestling. His professional debut came in 1947 at the age of 19 and with his blond hair, tanned, athletic build, and cocky mannerisms, Valentine quickly became one of the top stars in the business. His talent and toughness inside the ring frustrated many fans of the day, as the arrogant Valentine was as good as he bragged about being and he never let anyone forget it. As a result, in the eyes of the wrestling audience, he was among the most hated men of the era. That said, later in his career he occasionally wrestled as a tough-as-nails babyface and was equally successful in either role.

Johnny Valentine was born John Wisniski on September 22, 1928 in Hobart, Washington and originally he trained as a boxer before making the switch to wrestling. His professional debut came in 1947 at the age of 19 and with his blond hair, tanned, athletic build, and cocky mannerisms, Valentine quickly became one of the top stars in the business. His talent and toughness inside the ring frustrated many fans of the day, as the arrogant Valentine was as good as he bragged about being and he never let anyone forget it. As a result, in the eyes of the wrestling audience, he was among the most hated men of the era. That said, later in his career he occasionally wrestled as a tough-as-nails babyface and was equally successful in either role.

Johnny Valentine was famous for employing a notoriously methodical style of ring work during his matches, a style that most modern wrestling fans would likely find to be, at best, difficult to appreciate or, at worst, very boring. By working basic holds (i.e. a headlock, a leglock or perhaps an arm bar) for extended periods of time, he expertly incorporated genuine wrestling psychology into his matches. Meanwhile, his chops and forearm smashes were laid in with as much force as he could muster, which, to say the least, was considerable. Realism, not flash or wasted motion, was the mantra of Johnny Valentine and he was a true master at it. His matches, especially those against blood-enemies like Wahoo McDaniel, Dory Funk, Jr., The Sheik or Bobo Brazil, were some of the most violent, stiff, and realistic bouts that a wrestling fan could hope to witness.

The great Lou Thesz, who was a frequent opponent for many years, said of Valentine, “Easily the toughest guy I ever met. He was a two-fisted brawler who always tried his wings at wrestling. He enjoyed trying to hook me and put me in jeopardy, just to see if he could get away with it, and he was so strong and well-conditioned that he could’ve caused me considerable embarrassment if I hadn’t taken him seriously. I knew how to play the game a little better, though, because I’d had the expert coaching, but occasionally I’d have to use a hook on him, just to get away. If he’d had the kind of focused wrestling background I had, things could’ve been very different.”

The great Lou Thesz, who was a frequent opponent for many years, said of Valentine, “Easily the toughest guy I ever met. He was a two-fisted brawler who always tried his wings at wrestling. He enjoyed trying to hook me and put me in jeopardy, just to see if he could get away with it, and he was so strong and well-conditioned that he could’ve caused me considerable embarrassment if I hadn’t taken him seriously. I knew how to play the game a little better, though, because I’d had the expert coaching, but occasionally I’d have to use a hook on him, just to get away. If he’d had the kind of focused wrestling background I had, things could’ve been very different.”

Valentine’s list of championship accomplishments speaks for itself. In the tag team division, he won the Texas Tag Team championship with Rip Rogers (a.k.a. Eddie Graham) in 1958, followed by the NWA United States Tag Team title (which later evolved into the WWE World Tag Team championship) on November 14, 1959 with partner Dr. Jerry Graham. He also scored three more U.S. Tag Team titles wins with partners Buddy Rogers (1960), “Cowboy” Bob Ellis (1962) and Tony Parisi (1966), the Southern Tag Team title w/Boris Malenko in 1968, and five NWA International Tag Team championships. As a singles competitor, Valentine held, among other titles, three separate versions of the United States Heavyweight championship; the Toronto version (1963, 1968), the Detroit version (1964, twice in 1973) and the Mid-Atlantic version (the same U.S. title currently defended in WWE) in 1975. The talented Valentine also wore the coveted Florida Heavyweight title three times between 1967-68, the Southern Heavyweight championship in 1973, the NWF North American title in 1972, Japan’s United National Heavyweight title in 1973, and the NWA Eastern States Heavyweight title twice in 1974 and 1975. Although he was never an NWA World Heavyweight champion, Valentine did wear several prestigious regional versions of the World title, including the IWA (Chicago) World championship in 1963, the IWA (Montreal) World title in 1972, and the NWF World Heavyweight championship twice, in 1972 and 1973.

In addition to his many championship accolades, Johnny had intense, long-running feuds with some of the greatest stars of any era; Lou Thesz, Pat O’Connor, Harley Race, The Sheik, Wahoo McDaniel, Bruno Sammartino, Antonino Rocca, Bobo Brazil, Johnny Powers, the Brisco Brothers, Red Bastein, the Funks, and many, many others. He also produced an heir to his impressive legacy in the form of his very talented and successful son, Greg “The Hammer” Valentine. Although he was known as perhaps the toughest man in wrestling during his day, was an infamously “stiff ribber” among his co-workers, and his matches were often gory bloodfests, away from the ring, Johnny Valentine was quite different from the violent sadist he portrayed on television. A lover of opera, a player of chess and a connoisseur of fine wine, Valentine was truly an unlikely renaissance man.

In addition to his many championship accolades, Johnny had intense, long-running feuds with some of the greatest stars of any era; Lou Thesz, Pat O’Connor, Harley Race, The Sheik, Wahoo McDaniel, Bruno Sammartino, Antonino Rocca, Bobo Brazil, Johnny Powers, the Brisco Brothers, Red Bastein, the Funks, and many, many others. He also produced an heir to his impressive legacy in the form of his very talented and successful son, Greg “The Hammer” Valentine. Although he was known as perhaps the toughest man in wrestling during his day, was an infamously “stiff ribber” among his co-workers, and his matches were often gory bloodfests, away from the ring, Johnny Valentine was quite different from the violent sadist he portrayed on television. A lover of opera, a player of chess and a connoisseur of fine wine, Valentine was truly an unlikely renaissance man.

But, on October 4, 1975, the life of this legendary wrestler — and the world of professional wrestling — changed forever when Valentine (along with Ric Flair, David Crockett, Bob Bruggers and Tim Woods) were in a private plane, en route to another performance. While in flight, the plane literally ran out of fuel thousands of feet in the air and the result was a forgone conclusion, as it was only a matter of time before the small plane crashed to the ground below. The pilot eventually lost his life, while Flair and Bruggers both suffered broken backs. Meanwhile, Johnny Valentine was partially paralyzed. It was a tragedy that, while it could have been worse, was an understandably bitter pill to swallow for the proud Valentine. But, fate had left him with no options, professionally speaking, and his 28-year career as a wrestler was over, permanently.

But, on October 4, 1975, the life of this legendary wrestler — and the world of professional wrestling — changed forever when Valentine (along with Ric Flair, David Crockett, Bob Bruggers and Tim Woods) were in a private plane, en route to another performance. While in flight, the plane literally ran out of fuel thousands of feet in the air and the result was a forgone conclusion, as it was only a matter of time before the small plane crashed to the ground below. The pilot eventually lost his life, while Flair and Bruggers both suffered broken backs. Meanwhile, Johnny Valentine was partially paralyzed. It was a tragedy that, while it could have been worse, was an understandably bitter pill to swallow for the proud Valentine. But, fate had left him with no options, professionally speaking, and his 28-year career as a wrestler was over, permanently.

Not surprisingly, Johnny Valentine has been inducted into several Halls of Fame, including the Stampede Wrestling Hall of Fame (1995), the Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Fame (1996), the Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame (2006), the St. Louis Wrestling Hall of Fame (2007) and the NWA Hall of Fame (2011)

Not surprisingly, Johnny Valentine has been inducted into several Halls of Fame, including the Stampede Wrestling Hall of Fame (1995), the Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Fame (1996), the Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame (2006), the St. Louis Wrestling Hall of Fame (2007) and the NWA Hall of Fame (2011)

On April 24, 2001, John “Johnny Valentine” Wisniski passed away at the age of 72.

by Stephen Von Slagle

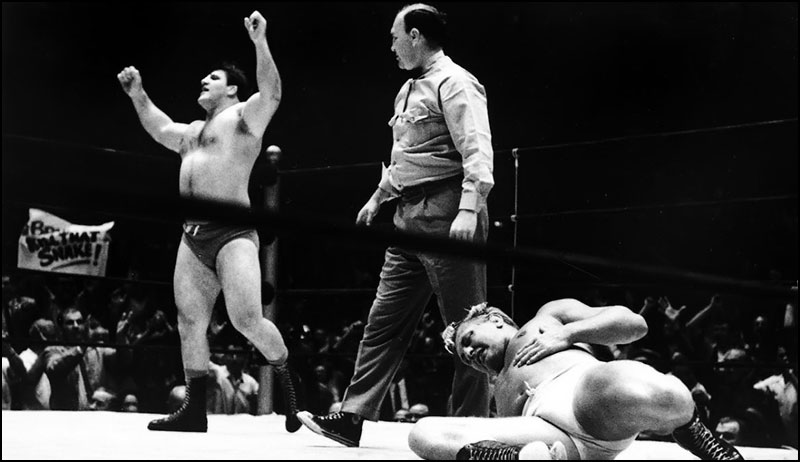

Bruno Sammartino is considered by many to be the overall greatest WWE champion in history, an opinion that is difficult to argue against. “The Living Legend” established the brand-new World Wide Wrestling Federation and gave credibility to Vince McMahon Sr.’s new heavyweight championship by building a fan base unlike anyone else until Hulk Hogan. During his first run as champion, the hugely popular Sammartino carried the WWWF title for 2,803 days, over seven and a half years, which is by far the longest continuous title reign in WWE history. Sammartino is also unquestionably the King of Madison Square Garden, WWE’s longtime home arena. However, contrary to wrestling lore, he did not sell-out Madison Square Garden 187 times. In fact, over the course of twenty-six years, Sammartino “only” made 159 appearances at the World’s Most Famous Arena. Furthermore, according to the best records available, “The Living Legend” had approximately 45 sell-outs of The Garden when wrestling in the main-event, either as a singles or tag team performer, an amazing accomplishment in itself and a feat that will likely never be matched by another WWE performer. During his two tenures as champion, Sammartino held the WWWF gold for over eleven years, 4,040 days in total, resulting in more WWE records that will almost surely never be broken.

“The Italian Superman” was born in Abruzzi, Italy on October 6, 1935, and, after an extremely trying time just managing to stay alive during the second World War, he immigrated to the United States, relocating to Pittsburgh, PA., at the age of 15. Sammartino began his wrestling career in December of 1959 and, although he was not necessarily a proficient technical wrestler, he was nevertheless an instant hit with fans and promoters. The youthful 5’10” 270 lb. powerlifter amazed his audiences with his immense strength while impressing matchmakers with his undeniable box-office appeal. After less than four years as a pro, a 28 year-old Sammartino won his first World Wide Wrestling Federation Heavyweight championship on May 17, 1963 by defeating the legendary “Nature Boy” Buddy Rogers in front of a captivated Madison Square Garden crowd. After Sammartino had defeated the respected and talented Rogers, the young champion seemed to go on a personal crusade to establish the fledgling new WWWF title as a legitimate World championship. He met and defeated the absolute biggest and best of his era, including Rogers, Killer Kowalski, George “The Animal” Steele, “Classy” Fred Blassie, Haystacks Calhoun, Gorilla Monsoon, Crusher Verdu, Waldo Von Erich, “Cowboy” Bill Watts and countless others during his nearly eight-year run as WWWF champ. His popularity grew to new, unseen heights along the East Coast during this time, as Bruno was as popular and well-known in the Big Apple as any New York Yankee. Furthermore, the chant of “Bruuun-o! Bruuun-o!” could be heard in Boston, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Baltimore, and every other major city that comprised the WWWF territory. To Northeastern fans throughout the decade of the 1960s, Bruno Sammartino was the literal epitome of professional wrestling.

“The Italian Superman” was born in Abruzzi, Italy on October 6, 1935, and, after an extremely trying time just managing to stay alive during the second World War, he immigrated to the United States, relocating to Pittsburgh, PA., at the age of 15. Sammartino began his wrestling career in December of 1959 and, although he was not necessarily a proficient technical wrestler, he was nevertheless an instant hit with fans and promoters. The youthful 5’10” 270 lb. powerlifter amazed his audiences with his immense strength while impressing matchmakers with his undeniable box-office appeal. After less than four years as a pro, a 28 year-old Sammartino won his first World Wide Wrestling Federation Heavyweight championship on May 17, 1963 by defeating the legendary “Nature Boy” Buddy Rogers in front of a captivated Madison Square Garden crowd. After Sammartino had defeated the respected and talented Rogers, the young champion seemed to go on a personal crusade to establish the fledgling new WWWF title as a legitimate World championship. He met and defeated the absolute biggest and best of his era, including Rogers, Killer Kowalski, George “The Animal” Steele, “Classy” Fred Blassie, Haystacks Calhoun, Gorilla Monsoon, Crusher Verdu, Waldo Von Erich, “Cowboy” Bill Watts and countless others during his nearly eight-year run as WWWF champ. His popularity grew to new, unseen heights along the East Coast during this time, as Bruno was as popular and well-known in the Big Apple as any New York Yankee. Furthermore, the chant of “Bruuun-o! Bruuun-o!” could be heard in Boston, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Baltimore, and every other major city that comprised the WWWF territory. To Northeastern fans throughout the decade of the 1960s, Bruno Sammartino was the literal epitome of professional wrestling.

However, as with all things in life, his record-setting 2,803 days as WWWF champion came to an inevitable end on January 17, 1971 when he was defeated by the mighty “Russian Bear” Ivan Koloff, who used his devastating top-rope Knee Drop to get the pin over the man that nobody could beat. The 22,000 in attendance at Madison Square Garden were so shocked to see Bruno pinned, cleanly, that after the final count was made and Koloff became the new champ, there was a stunned, surreal echo of silence and disbelief throughout the normally raucous crowd. It was truly a one-of-a-kind occurrence, never again repeated in the annals of WWE history. Following the loss of his championship, Sammartino took a sabbatical from the WWWF and, during one of his few non-WWWF ventures, he travelled to the Midwest and won the World Wrestling Association (WWA) World Tag Team title with Dick The Bruiser on July7, 1973. The duo, nicknamed “Annihilation Inc.,” defeated Ernie “The Big Cat” Ladd and Baron Von Raschke for the tag title and held onto the belts for nearly six months before being defeated by The Valiant Brothers.

Bruno returned to the Northeast and eventually met his successor, Pedro Morales, in the first-ever WWWF “babyface vs. babyface” championship encounter. The matchup, featuring the promotion’s two most popular wrestlers, took place on September 30, 1972 and drew over 22,500 spectators to Shea Stadium, going to a grueling 65-minute draw. Morales subsequently lost the WWWF title to Stan Stasiak on December 1, 1973, but Stasiak only held the title for nine days before Sammartino defeated him on December 10, 1973. This was the beginning of Bruno’s four year long, record-setting second WWWF title reign. Bruno is quoted as saying that the competition during his second reign was even tougher than the first, and one look at the men he defeated during these years will tell you why…Ken Patera, “Superstar” Billy Graham, Ivan Koloff, Bruiser Brody, Ernie Ladd, Tor Kamata, Spiros Arion, Nicolai Volkoff, Pampero Firpo, Baron Von Raschke, “Big, Bad” Bobby Duncum, Mr. Fuji, Prof. Toru Tanaka, Ox Baker, and many more all went down in defeat when matched against the powerful champion.

One wrestler who ended up giving Bruno quite a bit of trouble, one of his few defeats, and a legitimate broken neck to boot, was the wildman from West Texas State, Stan “The Lariat” Hansen. On April 26, 1976 Hansen not only defeated “The Living Legend” (via blood-stoppage) but actually delivered a clothesline with such force that it fractured Bruno’s vertebrae, breaking his neck. In reality, it was a botched body slam, not Hansen’s infamous Lariat, that broke Sammartino’s neck. But, the injury was nevertheless legitimate and devastating. The time away from the ring was long for Bruno’s fans, but not for Sammartino, as a mere two months after his injury took place, he was back in the ring at Vince McMahon, Sr.’s somewhat desperate request. McMahon had Shea Stadium booked for the closed-circuit Muhammad Ali vs. Antonio Inoki match and the advance ticket sales were underwhelming. The WWWF stood to lose a great deal of money unless something big happened to boost ticket sales. That “something” was a Sammartino vs. Hansen rematch, and the WWWF owner desperately needed for the bout to happen in order to make the event a success. Against the wishes of his doctors and family, Sammartino agreed and the match took place on June 25, 1976, drawing over 32,000 fans, the largest crowd to attend a card promoted by Vince McMahon, Sr. up to that point. To the delight of his legion of loyal fans, Bruno bloodied and battered “The Bad Man from Borger, Texas.” so badly that a crimson-masked Hansen eventually fled the ring in fear, disgrace and defeat.

One wrestler who ended up giving Bruno quite a bit of trouble, one of his few defeats, and a legitimate broken neck to boot, was the wildman from West Texas State, Stan “The Lariat” Hansen. On April 26, 1976 Hansen not only defeated “The Living Legend” (via blood-stoppage) but actually delivered a clothesline with such force that it fractured Bruno’s vertebrae, breaking his neck. In reality, it was a botched body slam, not Hansen’s infamous Lariat, that broke Sammartino’s neck. But, the injury was nevertheless legitimate and devastating. The time away from the ring was long for Bruno’s fans, but not for Sammartino, as a mere two months after his injury took place, he was back in the ring at Vince McMahon, Sr.’s somewhat desperate request. McMahon had Shea Stadium booked for the closed-circuit Muhammad Ali vs. Antonio Inoki match and the advance ticket sales were underwhelming. The WWWF stood to lose a great deal of money unless something big happened to boost ticket sales. That “something” was a Sammartino vs. Hansen rematch, and the WWWF owner desperately needed for the bout to happen in order to make the event a success. Against the wishes of his doctors and family, Sammartino agreed and the match took place on June 25, 1976, drawing over 32,000 fans, the largest crowd to attend a card promoted by Vince McMahon, Sr. up to that point. To the delight of his legion of loyal fans, Bruno bloodied and battered “The Bad Man from Borger, Texas.” so badly that a crimson-masked Hansen eventually fled the ring in fear, disgrace and defeat.

Bruno’s next great challenge came in the 6’4″, 275 pound, massively muscled frame of “Superstar” Billy Graham. After several prior attempts, the colorful and flamboyant “Superstar” Graham finally ended Bruno’s second reign, as a bloody Graham defeated Sammartino on April 30, 1977 in Baltimore, Maryland. The match ended in controversy, with Graham using the ropes illegally to gain the victory and the WWWF title. However, despite being cheated out of the championship, Bruno was never able to pin Graham’s massive shoulders to the mat and win back his title during any of their many rematches. Bruno’s career as the World Champion was finally over, this time forever. His career as one of wrestling’s top performers, however, was far from being ended.

In January of 1980, Larry Zbyszko turned violently on his former mentor during a televised “friendly” wrestling exhibition. The result was an epic feud that lasted for month after brutal month (and made the WWF a small fortune as the new decade began) that finally concluded when Bruno defeated Zbyszko inside of a steel cage in front of over 36,000 fans, again at Shea Stadium. A few years later, even with his age rapidly advancing and Vince McMahon, Jr’s “new” WWF ascending to unimagined heights, Bruno worked a few tag team matches with his son David and engaged in violent feuds with Roddy Piper, Randy Savage, and Adrian Adonis, with “The Living Legend” coming out the victor in them all. Those mid-1980s feuds turned out to be Bruno’s swan song and, in 1987, Sammartino retired from the ring for good. He still maintained a high-profile presence within the World Wrestling Federation, though, and alongside Vince McMahon and Jesse Ventura, Sammartino did color commentary on syndicated WWF programming. But, after a bitter series of professional and philosophical differences with WWF owner Vince McMahon, Bruno, with over twenty-five years of WWF tenure under his belt dating back to the literal beginning of the company, quit the Federation in 1988. After a few post-retirement dabblings in pro wrestling, namely working for Herb Abrams’ UWF and also WCW, Bruno left the sport altogether.

After leaving the WWF, Sammartino was very critical of Vince McMahon and the World Wrestling Federation, particularly during the company’s infamous steroid and sex scandals of the early-mid Nineties. The former champion, now an outspoken critic of the WWF, appeared on several high-profile television programs, including the Phil Donahue Show, Entertainment Tonight, Larry King Live, A Current Affair and Inside Edition, vociferously denouncing the company he helped build. A few years later, during the WWF’s controversial “Attitude Era,” Sammartino’s disdain for his former employer continued, sighting the promotion’s use of vulgarity and exploitation of women while still simultaneously catering to a fanbase made largely of children. However, as the WWF became the publicly-traded WWE, Sammartino’s strong anti-WWE stance softened, due primarily to the promotion’s new, more family-friendly product and the tireless efforts of Paul Leveque to bring the former champion back into the WWE “family.” Eventually, Leveque was successful and on April 6, 2013, at Madison Square Garden, Bruno Sammartino accepted his long overdue induction into the WWE Hall of Fame.

After leaving the WWF, Sammartino was very critical of Vince McMahon and the World Wrestling Federation, particularly during the company’s infamous steroid and sex scandals of the early-mid Nineties. The former champion, now an outspoken critic of the WWF, appeared on several high-profile television programs, including the Phil Donahue Show, Entertainment Tonight, Larry King Live, A Current Affair and Inside Edition, vociferously denouncing the company he helped build. A few years later, during the WWF’s controversial “Attitude Era,” Sammartino’s disdain for his former employer continued, sighting the promotion’s use of vulgarity and exploitation of women while still simultaneously catering to a fanbase made largely of children. However, as the WWF became the publicly-traded WWE, Sammartino’s strong anti-WWE stance softened, due primarily to the promotion’s new, more family-friendly product and the tireless efforts of Paul Leveque to bring the former champion back into the WWE “family.” Eventually, Leveque was successful and on April 6, 2013, at Madison Square Garden, Bruno Sammartino accepted his long overdue induction into the WWE Hall of Fame.

In addition to his induction into the WWE Hall of Fame, Sammartino is also a member of the Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Fame (1996), the Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame & Museum (2002) and the International Wrestling Institute & Museum’s George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame (2019).

In addition to his induction into the WWE Hall of Fame, Sammartino is also a member of the Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Fame (1996), the Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame & Museum (2002) and the International Wrestling Institute & Museum’s George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame (2019).

Following multiple organ failure due to heart complications, “The Living Legend” Bruno Sammartino passed away on April 18, 2018, at the age of 82. After his passing, Pittsburgh Mayor Bill Peduto called Sammartino “one of the greatest ambassadors the city of Pittsburgh ever had.”

by Stephen Von Slagle

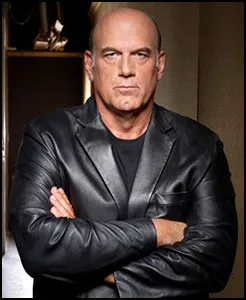

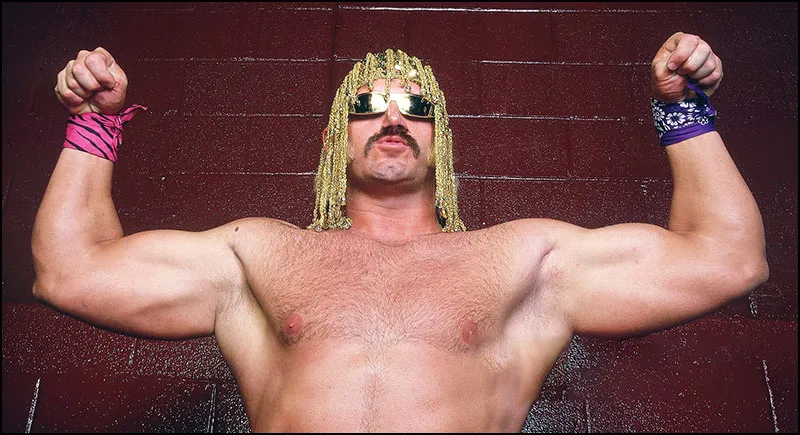

In a business filled with truly unique individuals, Jesse “The Body” Ventura is a persona like few others. While never considered a great worker in the ring, behind the microphone he was undoubtedly one of the best ever and one of wrestling’s biggest stars. Ultimately, he is a man driven by the will to succeed. Be it as a Navy Seal, a professional wrestler, a color commentator, an actor, talk show host, best-selling author or politician, once Ventura becomes focused on a goal, it seems nothing can stop him. The epitome of the phrase “You can’t judge a book by its cover,” on the surface this determined, multi-dimensional man is an unlikely hero. But, once you dig a little deeper into his personal history, it can be argued that a better role model could not be found.

Jim Janos, the future Jesse “The Body” Ventura, was born into a middle-class, blue-collar family on July 15, 1951 in St. Paul, Minnesota. As a youth, Janos quickly developed a love for sports, two of his favorites being competitive swimming and professional wrestling. Upon graduation from high school in 1969, he enlisted into the Navy during the height of the Vietnam war. Once in the Navy, he endured the personal sacrifices as well as the rigorous mental and physical training that it took in order to become a Navy Seal. Janos had what it took, and he completed several tours of duty as part of the elite fighting group’s underwater demolition team. Once he was back in the United States, Janos, like many returning Vietnam vets, had little direction in life upon his return. He found his way to southern California, where he rode with a motorcycle gang, the Mongols. But, after a few years Janos realized that the biker lifestyle wasn’t really leading him anywhere and he moved back to Minnesota. Once he had returned home, Janos enrolled at Hennipen Jr. College, where he played football. As had always been the case, he was a standout in sports and a mere participant in class. Eventually, he dropped out of college and into something entirely different. While working out at a local gym, the 6`3″ 250 lb. Janos was first introduced to people within the professional wrestling business. Already a lifelong fan of the sport, it didn’t take much to convince Jim to give wrestling a shot. After receiving his formal training from Eddie Sharkey, Janos developed his new wrestling persona, California surfer-guy Jesse Ventura, and made his pro debut in 1975 against veteran journeyman Omar Atlas.

Jim Janos, the future Jesse “The Body” Ventura, was born into a middle-class, blue-collar family on July 15, 1951 in St. Paul, Minnesota. As a youth, Janos quickly developed a love for sports, two of his favorites being competitive swimming and professional wrestling. Upon graduation from high school in 1969, he enlisted into the Navy during the height of the Vietnam war. Once in the Navy, he endured the personal sacrifices as well as the rigorous mental and physical training that it took in order to become a Navy Seal. Janos had what it took, and he completed several tours of duty as part of the elite fighting group’s underwater demolition team. Once he was back in the United States, Janos, like many returning Vietnam vets, had little direction in life upon his return. He found his way to southern California, where he rode with a motorcycle gang, the Mongols. But, after a few years Janos realized that the biker lifestyle wasn’t really leading him anywhere and he moved back to Minnesota. Once he had returned home, Janos enrolled at Hennipen Jr. College, where he played football. As had always been the case, he was a standout in sports and a mere participant in class. Eventually, he dropped out of college and into something entirely different. While working out at a local gym, the 6`3″ 250 lb. Janos was first introduced to people within the professional wrestling business. Already a lifelong fan of the sport, it didn’t take much to convince Jim to give wrestling a shot. After receiving his formal training from Eddie Sharkey, Janos developed his new wrestling persona, California surfer-guy Jesse Ventura, and made his pro debut in 1975 against veteran journeyman Omar Atlas.

Ventura created his first waves within the business while competing for the NWA’s Central States territory. In terms of the NWA’s hierarchy, the Kansas City-based promotion was not one of the sport’s major players, but it was one of the best training grounds for young, inexperienced wrestlers trying to learn and perfect their craft. Ventura openly admits that he initially modeled nearly every facet of his new persona after his favorite wrestler, the legendary “Superstar” Billy Graham, who was then at the height of his popularity and influence. With his new Graham-ish persona complete, Jesse Ventura emerged as a major force in Central States Wrestling. Right around the same time he started his successful run in Central States, the rookie Ventura also began wrestling in Portland’s Pacific Northwest Wrestling which, much like Central States, was another “training ground” type of promotion. And, like Central States, it produced a number of future superstars who were, at the time, unknown to the wrestling world at large.

He engaged in a particularly intense feud with Jimmy Snuka while wrestling in Portland and twice wore the Pacific Northwest Heavyweight title belt in 1976. Ventura also won five Pacific Northwest Tag Team championships (w/partners Bull Ramos, Buddy Rose, and Ted Oates) between 1976-78. Back in Kansas City, Ventura teamed with local powerhouse Tank Patton to win the Central States Tag Team title on September 14, 1978, his only championship in the midwestern promotion. Having paid his dues, gained valuable experience and perfected his wrestling style (Ventura was never known as a great technical wrestler, but made the most of his limited repertoire) it was finally time for Jesse Ventura to move up to the “big time.” He returned home to Minnesota and began working for Verne Gagne’s American Wrestling Association in 1979. It was in the AWA that Ventura first broke onto the national wrestling scene, as fans across the country realized what people in the Portland and Central States territories already knew; Jesse Ventura was going to be a big star in the wrestling business.

He engaged in a particularly intense feud with Jimmy Snuka while wrestling in Portland and twice wore the Pacific Northwest Heavyweight title belt in 1976. Ventura also won five Pacific Northwest Tag Team championships (w/partners Bull Ramos, Buddy Rose, and Ted Oates) between 1976-78. Back in Kansas City, Ventura teamed with local powerhouse Tank Patton to win the Central States Tag Team title on September 14, 1978, his only championship in the midwestern promotion. Having paid his dues, gained valuable experience and perfected his wrestling style (Ventura was never known as a great technical wrestler, but made the most of his limited repertoire) it was finally time for Jesse Ventura to move up to the “big time.” He returned home to Minnesota and began working for Verne Gagne’s American Wrestling Association in 1979. It was in the AWA that Ventura first broke onto the national wrestling scene, as fans across the country realized what people in the Portland and Central States territories already knew; Jesse Ventura was going to be a big star in the wrestling business.

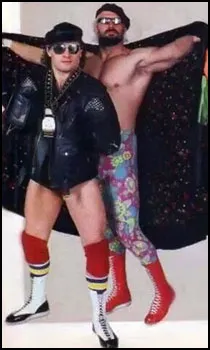

Once in the AWA, Jesse was initially managed by Bobby Heenan and he wrestled both as a singles competitor (engaging in a “body building” feud with the equally young “Precious” Paul Ellering) and in tag teams with various Heenan Family members, such as “Big, Bad” Bobby Duncum. But when he was paired with another young superstar-in-the-making, Adrian Adonis, Ventura’s career advanced to the next level. On July 20, 1980, Ventura & Adonis, the East-West Connection, were awarded the AWA World Tag Team title when reigning champions Verne Gagne & “Mad Dog” Vachon no-showed a scheduled defense in Denver. Although the championship had been “given” to them, Ventura & Adonis gelled as a team and it quickly became obvious that the duo was something special. The East-West Connection reigned as AWA World Tag Team champions for nearly an entire year before losing their belts to The High Flyers, Greg Gagne & Jim Brunzell, on June 14, 1981.

After dominating the American Wrestling Association, Ventura and Adonis ventured northeast to the World Wrestling Federation. With Freddie Blassie as their manager, The East-West Connection both set their sights on WWF Heavyweight champion Bob Backlund. Blassie promised fans that his one-two punch of Ventura and Adonis was sure to be the knockout blow that would topple Backlund off of his WWF throne. History proved that this was not to be the case, but Ventura’s first run in the WWF was nevertheless another career-booster. With fans in the midwest and the northeast having been exposed to Jesse “The Body” Ventura, he left the WWF and headed south to Memphis. During his stay in “the King’s court,” Ventura twice defeated Memphis legend Jerry “The King” Lawler for the prestigious Southern Heavyweight title in 1983. As part of Jimmy Hart’s First Family, Ventura occasionally teamed with the rugged Stan Hansen and the two battled Lawler and Austin Idol both in singles and tag team matches.

Following his run in Memphis, Ventura returned to the AWA and resumed his feud with the promotion’s top babyfaces, in particular, The Crusher as well as “The Incredible” Hulk Hogan. However, by this time Vincent K. McMahon’s WWF was in the midst of its nationwide expansion and, early on, Verne Gagne’s AWA was singled out by McMahon as the prime source of new talent for the Federation. Like dozens of wrestlers before and after him, Ventura left the AWA for the WWF and once there, engaged in major, main-event feuds with Tony Atlas, Ivan Putski, and, in particular, Intercontinental champion Tito Santana. But, by the mid-1980’s, Ventura’s body began to break down from the constant punishment he received in the ring. After developing a nearly lethal blood clot, Ventura decided to step away rather than risk his life and he retired in 1986 after eleven years of in-ring competition. With the retirement of Jesse Ventura, the world of wrestling lost a major box-office attraction, however, with that loss came an unexpected gain…

Following his run in Memphis, Ventura returned to the AWA and resumed his feud with the promotion’s top babyfaces, in particular, The Crusher as well as “The Incredible” Hulk Hogan. However, by this time Vincent K. McMahon’s WWF was in the midst of its nationwide expansion and, early on, Verne Gagne’s AWA was singled out by McMahon as the prime source of new talent for the Federation. Like dozens of wrestlers before and after him, Ventura left the AWA for the WWF and once there, engaged in major, main-event feuds with Tony Atlas, Ivan Putski, and, in particular, Intercontinental champion Tito Santana. But, by the mid-1980’s, Ventura’s body began to break down from the constant punishment he received in the ring. After developing a nearly lethal blood clot, Ventura decided to step away rather than risk his life and he retired in 1986 after eleven years of in-ring competition. With the retirement of Jesse Ventura, the world of wrestling lost a major box-office attraction, however, with that loss came an unexpected gain…

As a color commentator, Ventura changed the face of WWF broadcasts with his “I call it like I see it” pro-heel stance. As the color man for WWF PPV’s, the NBC Saturday Night’s Main Event program and the WWF’s Prime Time Wrestling (with co-host Gorilla Monsoon) show on the USA Network, Ventura, and his distinctive voice, was a part of nearly every memorable WWF moment from the mid to late 1980s. Ventura then used his fame and talent to land leading parts in major films such as Demolition, Predator and The Running Man and by the end of the decade, he was a genuine household name. His independent streak created certain problems between Ventura and WWF owner Vince McMahon, though, problems concerning his plans to form a wrestlers’ union as well as his insistence on being paid royalties for WWF video sales. In 1990, Ventura quit the promotion and, in 1994, he received over $800,000.00 when a federal jury found that McMahon had wrongfully withheld royalties owed to Ventura. After leaving the WWF, he continued to pursue his career in Hollywood, with a good deal of success, yet Ventura remained out of the picture when it came to pro wrestling. But, with the dawn of the new decade, he re-emerged as a wrestling personality early in 1992, this time with the promotion that Ventura called “the wrestling of the future,” Ted Turner’s World Championship Wrestling. As the color commentator for all WCW pay-per-views, Clash of the Champions specials, and TBS’s WCW Saturday Night from 1992-1994, Ventura once again left his indelible mark on professional wrestling and seemingly rounded-out his career in the process.

As a color commentator, Ventura changed the face of WWF broadcasts with his “I call it like I see it” pro-heel stance. As the color man for WWF PPV’s, the NBC Saturday Night’s Main Event program and the WWF’s Prime Time Wrestling (with co-host Gorilla Monsoon) show on the USA Network, Ventura, and his distinctive voice, was a part of nearly every memorable WWF moment from the mid to late 1980s. Ventura then used his fame and talent to land leading parts in major films such as Demolition, Predator and The Running Man and by the end of the decade, he was a genuine household name. His independent streak created certain problems between Ventura and WWF owner Vince McMahon, though, problems concerning his plans to form a wrestlers’ union as well as his insistence on being paid royalties for WWF video sales. In 1990, Ventura quit the promotion and, in 1994, he received over $800,000.00 when a federal jury found that McMahon had wrongfully withheld royalties owed to Ventura. After leaving the WWF, he continued to pursue his career in Hollywood, with a good deal of success, yet Ventura remained out of the picture when it came to pro wrestling. But, with the dawn of the new decade, he re-emerged as a wrestling personality early in 1992, this time with the promotion that Ventura called “the wrestling of the future,” Ted Turner’s World Championship Wrestling. As the color commentator for all WCW pay-per-views, Clash of the Champions specials, and TBS’s WCW Saturday Night from 1992-1994, Ventura once again left his indelible mark on professional wrestling and seemingly rounded-out his career in the process.

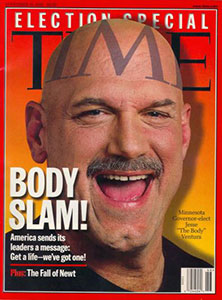

It was during his WCW tenure that Ventura became inspired to run in the mayoral elections of his hometown of Brooklyn Park, Minnesota, which he won. Ventura’s political victory made headlines across the country and once again solidified Jesse’s place in American pop (and now, political) culture. However, when his stay in WCW came to a somewhat bitter end, thanks initially to issues with then-WCW Vice President Bill Watts and, later, Hulk Hogan, Ventura left WCW and retired from professional wrestling. As had been the case some twenty years earlier, it was time for Jesse Ventura (who by this point had legally changed his name from Jim Janos) to look for new challenges.

At first, a successful run as a radio talk show host served as Ventura’s new outlet. However, no one could’ve imagined that his new career path would lead him to the Governorship of the state of Minnesota, although that’s exactly what happened. Ventura had an open forum each day to discuss the issues on his radio program and he used it to his advantage. Taking an “everyman” approach to politics, Ventura seized every opportunity to get his message to the voters of Minnesota. After running a frugal, grass-roots campaign, Ventura, running on the Reform ticket, literally stunned the world when he defeated the firmly established, well-funded Democrat and Republican candidates by a substantial margin and won the Governorship. As a result, Ventura appeared on the cover of Time magazine, the only wrestling personality ever to do so. His image was plastered on every available media outlet, and the confused, elitist press scratched their collective head. Following his historic victory, “Jesse ‘The Body’ Ventura is the new Governor of Minnesota?!?” was the prevailing attitude among political pundits across the nation. Some called it refreshing, many called it a joke. The fact remained, though, that the trailblazing Ventura shocked everyone when he won his election.