by Stephen Von Slagle

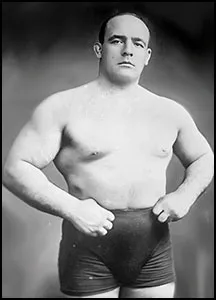

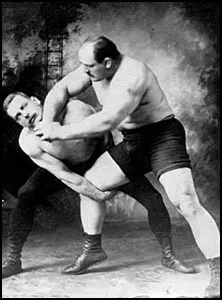

Throughout its long history, professional wrestling has always featured powerlifters, bodybuilders and strongmen of all sorts. While possessing a Herculean physique is surely beneficial to a pro wrestler’s career, if takes more than strength to excel in the ring and, certainly, this was the case during the early days of pro wrestling, before the era of the worked match fully took hold. At the turn of the previous century, when legitimate contests were still quite prevalent, sheer strength was, for the most part, not enough to get by on. Indeed, the wrestlers of that era, even the most physically powerful, needed at least some rudimentary grappling skills simply to stay competitive. Of course, if a strongman happened to have some technical wrestling knowledge, particularly in the art of shooting, his opponent could quickly find himself in a very precarious position. This was definitely the case of the Polish juggernaut, Stanislaus Zbyzsko, who combined power and ability with impressive results. During his prime in the early twentieth century, Zbyzsco was unquestionably one of the sport’s top competitors; a legitimately dangerous man who would go on to become a legendary World champion.

He was born Stanislaus Cyganiewicz on April 1, 1878, in Jodlawa, Poland. Originally, he excelled at the traditional Greco-Roman wrestling, however, with the decline of that particular wrestling genre, he quickly adapted to the newer ‘freestyle’ type of grappling, which was much more reminiscent of modern pro wrestling than the slow moving, heavily regulated Greco-Roman style. In terms of professional wrestling, Zbyzsko first came into prominence when, after building a solid string of victories throughout Europe, he traveled to Great Britain, a country in which professional wrestling was experiencing a huge boom in popularity. In 1907, the brawny Pole came to an arrangement with C.B. Cochran, the controversial former manager of Britain’s top box-office draw, “The Russian Lion” George Hackenschmidt. Cochran, a true impresario if ever one existed, quickly took steps to ensure that Zbyzsko filled the void left by the departed Hackenschmidt (who, by then, had traveled overseas to compete in the U.S.). However, unlike the handsome and popular “Russian Lion,” Zbyzsko was not loved nor cheered by the large crowds who turned out for his matches. In fact, the rugged and intimidating Zbyzsko was often the recipient of the audience’s jeers. Still, despite the fact that he was not particularly well-liked by the public, Cochran’s newest charge nevertheless went on to establish himself as Britain’s top post-Hackenschmidt attraction.

He was born Stanislaus Cyganiewicz on April 1, 1878, in Jodlawa, Poland. Originally, he excelled at the traditional Greco-Roman wrestling, however, with the decline of that particular wrestling genre, he quickly adapted to the newer ‘freestyle’ type of grappling, which was much more reminiscent of modern pro wrestling than the slow moving, heavily regulated Greco-Roman style. In terms of professional wrestling, Zbyzsko first came into prominence when, after building a solid string of victories throughout Europe, he traveled to Great Britain, a country in which professional wrestling was experiencing a huge boom in popularity. In 1907, the brawny Pole came to an arrangement with C.B. Cochran, the controversial former manager of Britain’s top box-office draw, “The Russian Lion” George Hackenschmidt. Cochran, a true impresario if ever one existed, quickly took steps to ensure that Zbyzsko filled the void left by the departed Hackenschmidt (who, by then, had traveled overseas to compete in the U.S.). However, unlike the handsome and popular “Russian Lion,” Zbyzsko was not loved nor cheered by the large crowds who turned out for his matches. In fact, the rugged and intimidating Zbyzsko was often the recipient of the audience’s jeers. Still, despite the fact that he was not particularly well-liked by the public, Cochran’s newest charge nevertheless went on to establish himself as Britain’s top post-Hackenschmidt attraction.

Playing on Zbyzsko’s expanded vocabulary and studious disposition, Cochran concocted a public persona for Zbyzsko that presented the Polish strongman as an intellectual elitist, a master chess player, and someone who was fluent in no less than twenty languages. The Englishman devised elaborate publicity stunts for his wrestler and always made sure there was a reason for Zbyzsko’s name to be in the newspapers. Meanwhile, Zbyzsko held up his end of the arrangement by defeating (in many cases, legitimately) all comers, and his highly publicized bouts with Kara Suliman and Ivan Padoubney drew overflow crowds that turned away thousands.

By the time he was in his mid-twenties, the hulking yet intellectual Zbyszko had become one of Europe’s top attractions. Known far and wide for his immense strength, as well as for possessing a surprising amount of technical wrestling knowledge and ability for a man of his size, Zbyszko gained a well deserved reputation as a truly dangerous and formidable shooter. However, perhaps more importantly, when it came to drawing crowds, the mighty Zbyszko was even more impressive and it was not an uncommon occurrence for hundreds (and in many cases, thousands) of spectators to be turned away from his sold-out matches throughout Great Britain, particularly in London. Yet, Stanislaus Zbyszko’s greatest success awaited him in the United States and it was in 1909 that the rugged European made his American debut, with one consuming goal…becoming the World Heavyweight champion. Far from the most beloved of competitors, he was nevertheless as successful in the States as he had been in London and Zbyszko, who was highly popular with the many Polish immigrants living in the U.S., quickly found himself matched against the popular World Heavyweight champion, Frank Gotch.

By the time he was in his mid-twenties, the hulking yet intellectual Zbyszko had become one of Europe’s top attractions. Known far and wide for his immense strength, as well as for possessing a surprising amount of technical wrestling knowledge and ability for a man of his size, Zbyszko gained a well deserved reputation as a truly dangerous and formidable shooter. However, perhaps more importantly, when it came to drawing crowds, the mighty Zbyszko was even more impressive and it was not an uncommon occurrence for hundreds (and in many cases, thousands) of spectators to be turned away from his sold-out matches throughout Great Britain, particularly in London. Yet, Stanislaus Zbyszko’s greatest success awaited him in the United States and it was in 1909 that the rugged European made his American debut, with one consuming goal…becoming the World Heavyweight champion. Far from the most beloved of competitors, he was nevertheless as successful in the States as he had been in London and Zbyszko, who was highly popular with the many Polish immigrants living in the U.S., quickly found himself matched against the popular World Heavyweight champion, Frank Gotch.

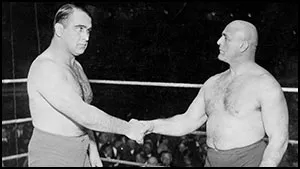

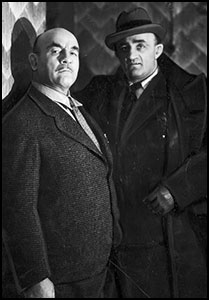

Stanislaus Zbyszko and brother Wladek Zbyszko

Knowing the strength and skill of his latest challenger, Gotch was understandably hesitant to defend his World title against Zbyszko. However, his personal pride as a champion and the demand for a Gotch-Zbyszko match by the wrestling public forced the cunning Gotch into facing the Polish juggernaut. As the champion, Gotch was well aware of his clout, and he demanded that their first encounter be a non-title bout. Buffalo, New York was the site of the first Gotch vs. Zbyszko showdown and the legendary hour-long draw from 1909 went down as a true classic in the annals of professional freestyle wrestling. The following year, a rematch was held in Chicago, which was at that time (and for many years afterward) the undisputed center of the professional wrestling universe. Accounts of the rematch describe a wild affair, highlighted by great controversy. Allegedly, just prior to the start of the first fall, Zbyszko extended his hand to Gotch, which was a common display of sportsmanship during the era. However, instead of shaking his challenger’s hand, it is said that Gotch took the unprepared Zbyszko down with a leg dive, and after grounding his larger opponent, Gotch applied a half-nelson for a startlingly quick first fall victory. Although it was said to have been a pro-Gotch crowd, Zbyszko also had his share of fans, who were incensed by Gotch’s unsportsmanlike tactics. In fact, several irate spectators reportedly stormed the ringside area and broke one of the ring posts before being escorted out of the arena by security. Once order had been restored and the situation was back under control, the second fall began. Following close to thirty minutes of solid wrestling, during which Zbyszko controlled much of the match, Gotch’s superior technique won out and Zbyszko was defeated without incident. Given the fact that the second fall had been so decisive, despite the controversy of the first fall, Gotch’s victory stood and he remained the World Champion.

The outbreak of World War I temporarily put the careers of many wrestlers on hold and Zbyszko was no exception. However, following the war, the aging but still capable Zbyszko returned from Britain and reclaimed his spot at the top of the pro wrestling world. By this time, however, any trace of legitimate contests were all but gone, and the outcomes of nearly all wrestling matches were predetermined. The versatile Zbyszko once again adapted to the ever-changing sport, and made the East Coast (particularly the Northeastern portion of the country) his primary base of operations following the war. On May 6, 1921, Zbyszko made history when he met and defeated the legendary Ed “Strangler” Lewis for New York’s version of the World championship at Madison Square Garden.

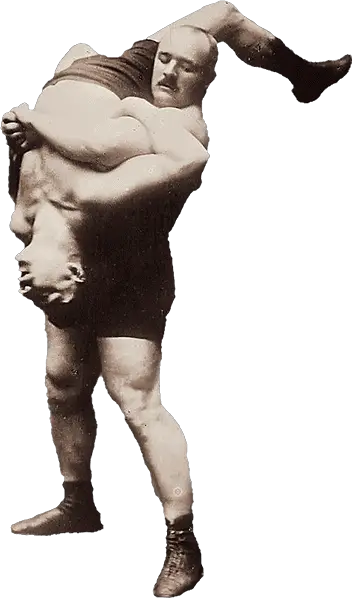

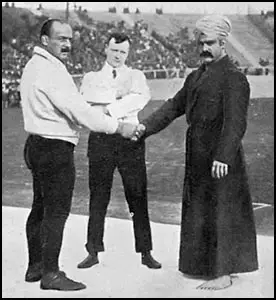

Stanislaus Zbyszko meets Great Gama

Although he was generally considered to be past his prime by the time he won the title, Zbyszko was nevertheless a fighting champion and he held the belt for nearly a full year before being defeated by Lewis in a rematch held in Wichita, Kansas. Then, some three years later, Zbyszko again won the East Coast version of the World title when he legitimately defeated Wayne Munn in Philadelphia on April 15, 1925. As per an agreement with promoter Tony Stecher, Zbyszko then dropped the title a short time later to Joe Stecher in St. Louis, thus ending his run with the World championship. However, his drawing power (which stemmed not from popularity, but rather, people turning out with the hope of seeing the Polish strongman being defeated) was not limited to Europe and the United States. When he traveled to India in 1928 to face the legendary Great Gama, Zbyszko helped draw more than 60,000 spectators for their match, the largest audience ever for a wrestling event in that nation’s history. Not long after his bout with Gama, the veteran retired from the sport, following a stellar career.

Stanislaus Zbyszko is a member of the National Polish-American Sports Hall of Fame (1983), the Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Fame (1996), the Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame (2003) and the International Wrestling Institute & Museum’s George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame (2010).

Stanislaus Zbyszko is a member of the National Polish-American Sports Hall of Fame (1983), the Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Fame (1996), the Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame (2003) and the International Wrestling Institute & Museum’s George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame (2010).

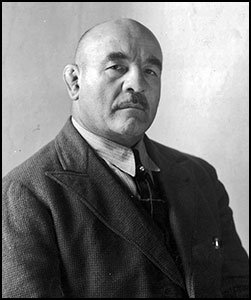

Stanislaus (Zbyszko) Cyganiewicz passed away on September 23, 1967 at the age of 88.