ssa

by Mark Long

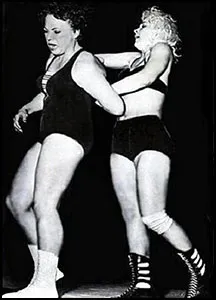

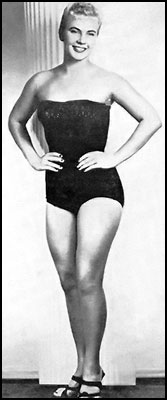

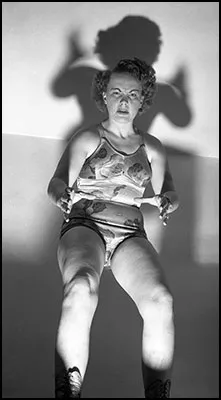

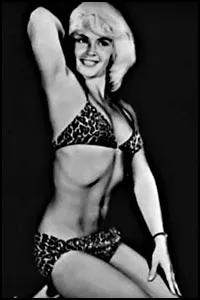

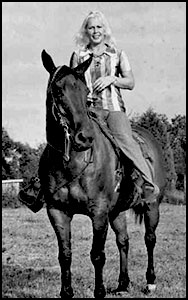

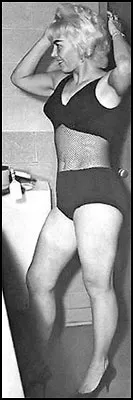

She was the total package as a professional wrestler. Incredibly beautiful with a great figure, she was type of eye candy that promoters could use to fill their arenas. But June Byers was an incredibly tough, technical wrestler, who could hold her own with the greats in any era of the business.

June Byers was born DeAlva Eyvonnie Sibley in Houston, Texas on May 25, 1922. She was the daughter of Arthur Sibley, a house painter, and Ruby Lee Cooke. Delva had two older sisters and a younger brother and grew up as something of a tomboy. Her Uncle, Ottoway “Shorty” Roberts, worked for Morris Sigel, a Houston-based wrestling promoter, so DeAlva was around the business as a youngster. She was an excellent athlete, and her uncle had begun training her in conditioning at the age of seven. Because of her connections, she was able to barrage local wrestlers with questions about wrestling holds and maneuvers and as a young lady she was able to get many of them to help her to further her training. As luck (or fate) would have it, one of the days when she was working out in the ring she was observed by women’s wrestling promoter Billy Wolfe. In addition to being the most powerful women’s promoter in the world, Wolfe was also married to Mildred Burke, the top female wrestler in the world, and the current champion. Wolfe was always on the lookout for a woman with potential as a wrestler and he had Shorty make an introduction.

June Byers was born DeAlva Eyvonnie Sibley in Houston, Texas on May 25, 1922. She was the daughter of Arthur Sibley, a house painter, and Ruby Lee Cooke. Delva had two older sisters and a younger brother and grew up as something of a tomboy. Her Uncle, Ottoway “Shorty” Roberts, worked for Morris Sigel, a Houston-based wrestling promoter, so DeAlva was around the business as a youngster. She was an excellent athlete, and her uncle had begun training her in conditioning at the age of seven. Because of her connections, she was able to barrage local wrestlers with questions about wrestling holds and maneuvers and as a young lady she was able to get many of them to help her to further her training. As luck (or fate) would have it, one of the days when she was working out in the ring she was observed by women’s wrestling promoter Billy Wolfe. In addition to being the most powerful women’s promoter in the world, Wolfe was also married to Mildred Burke, the top female wrestler in the world, and the current champion. Wolfe was always on the lookout for a woman with potential as a wrestler and he had Shorty make an introduction.

Most people had a hard time pronouncing her name, almost as hard of a time as her parents had choosing one. Although she was born in May, her parents were unable to settle on her name until June and most of the family thus referred to her as June. By the time she signed with Wolfe’s promotion, she had already been married and divorced to a man with the last name Byers, and so, as she entered professional wrestling, she did so under the name of June Byers.

Most people had a hard time pronouncing her name, almost as hard of a time as her parents had choosing one. Although she was born in May, her parents were unable to settle on her name until June and most of the family thus referred to her as June. By the time she signed with Wolfe’s promotion, she had already been married and divorced to a man with the last name Byers, and so, as she entered professional wrestling, she did so under the name of June Byers.

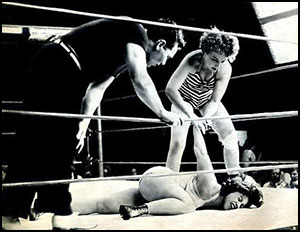

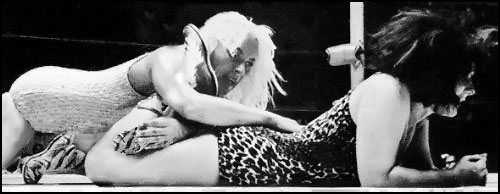

She was trained, at times, by former NCAA Light Heavyweight champion Ruffy Silverstein and hard nosed lady wrestler Mae Young. Young fought as tough as a man and was impressed with the toughness that June showed in the ring. Byers debuted in 1944 at a Ladies’ Battle Royal in Norfolk, Virginia and spent the next few years touring the country wrestling in Wolfe’s troop, usually on the losing side of matches against veteran opponents including Young and champion Burke. Everyone saw great potential in Byers, but considering the dearth of women wrestlers in the business, they were all vying for a top spot. Unfortunately, that left a pathway for obtaining top positions by way of familiarity with the boss. In Pat Laprade and Dan Murphy’s Sisterhood of the Squared Circle the authors stated that Wolfe would demand that applicants to his promotion be “single, intelligent, physically agile, and sound of character,” as well as photogenic. This appeal to beauty was not only for the enjoyment of the wrestling fans, but also for Wolfe himself. He was notorious for pursuing sexual liaisons with his lady wrestlers, with Freddie Blassie once calling him a pimp. Many of his girls were reported to have exchanged sexual favors for a spot on the roster, something that would surround Byers in controversy later in her career.

Over the next eight years, June was wrestling constantly, improving and moving up in the rankings. She performed against noted wrestlers including Millie Stafford, Penny Banner, Nell Stewart, Young, Burke, and Elvira Snodgrass. She developed a wrestling maneuver called the “Byers’ Bridge” that she used as a finishing hold. As documented in The WAWLI Papers #579 she said that “I actually developed the hold accidentally“, she said. “During a match I grabbed an opponent’s hands, they fell back with my legs in between, hooking them, I bridged back in a suplex for a winning pin, and that is how the hold was developed. Actually my opponent’s momentum carried me backwards, so although I found a new hold and won a match, it happened in such a manner that I almost knocked my brains out doing it.”

Over the next eight years, June was wrestling constantly, improving and moving up in the rankings. She performed against noted wrestlers including Millie Stafford, Penny Banner, Nell Stewart, Young, Burke, and Elvira Snodgrass. She developed a wrestling maneuver called the “Byers’ Bridge” that she used as a finishing hold. As documented in The WAWLI Papers #579 she said that “I actually developed the hold accidentally“, she said. “During a match I grabbed an opponent’s hands, they fell back with my legs in between, hooking them, I bridged back in a suplex for a winning pin, and that is how the hold was developed. Actually my opponent’s momentum carried me backwards, so although I found a new hold and won a match, it happened in such a manner that I almost knocked my brains out doing it.”

Billy had her wrestling in a lot of preliminary matches, but imagined her being a much greater star. In the closing days of the 1940’s, Wolfe’s marriage to Mildred Burke had become strained. Burke was aware of his womanizing and was frustrated with his increased interest in preparing other women to take her place. In addition, Wolfe’s son, Bill, Jr., had begun working for the promotion as Mildred’s driver, and confessed to his father that he had fallen in love with her and wanted to marry her… his stepmother. His father laughed at him but this demonstrated the turmoil building within the family and within the promotion.

On October 4, 1952, June enjoyed her first taste of title success, teaming up with Millie Stafford to win the Women’s World Tag Team Championship, defeating Ella Waldek and Mae Young in Mexico City, Mexico. She would end up holding the tag title belts on five occasions with partners Stafford (twice), Mary Jane Mull, Mars Bennett and Barbara Baker. Burke had been injured the previous year in an automobile accident and was advised to take six months off to heal, without having to forfeit the belt. Wolfe, however, insisted on her getting back into the ring to continue touring. Behind her back, he was planning to push her out of the picture and replace her with his current girlfriend, Nell Stewart. When Burke learned of this she assured him that she would not drop the belt to her for any reason. Wolfe responded (along with Bill, Jr., who was now married to June) by beating her up in a parking lot in front of her five year old son. This added broken ribs and facial lacerations to the injuries she had previously suffered in the automobile accident. When Mildred missed an NWA convention because of injuries, Wolfe told members that Burke was suffering from cancer and that her career was coming to an end. Eventually Burke and Wolfe divorced and through arbitration by the NWA board, they agreed that she would buy exclusive rights to the women’s title belt for $30,000.00 and that Wolfe would refrain from promoting women’s wrestling for a period of five years. Wolfe, however, had no intention of following through with this commitment and continued promoting, while looking for a way of supplanting Mildred as the new champion. With Wolfe being an NWA member and Burke prohibited from membership by virtue of her sex, the NWA allowed him to arrange a new tournament to crown a new women’s champion. Burke found out about the tournament and informed the Baltimore Sun that the results of the tournament had been decided and that Nell Stewart was going to be crowned the new champion. Embarrassed and painted into a corner, Wolfe switched plans and at the end of the tournament on June 14, 1953 in Baltimore, Maryland, June Byers pinned Nell Stewart to become the new Women’s World Champion. Burke thought otherwise, in that she had not actually lost the belt in a match and continued to call herself the champion.

On October 4, 1952, June enjoyed her first taste of title success, teaming up with Millie Stafford to win the Women’s World Tag Team Championship, defeating Ella Waldek and Mae Young in Mexico City, Mexico. She would end up holding the tag title belts on five occasions with partners Stafford (twice), Mary Jane Mull, Mars Bennett and Barbara Baker. Burke had been injured the previous year in an automobile accident and was advised to take six months off to heal, without having to forfeit the belt. Wolfe, however, insisted on her getting back into the ring to continue touring. Behind her back, he was planning to push her out of the picture and replace her with his current girlfriend, Nell Stewart. When Burke learned of this she assured him that she would not drop the belt to her for any reason. Wolfe responded (along with Bill, Jr., who was now married to June) by beating her up in a parking lot in front of her five year old son. This added broken ribs and facial lacerations to the injuries she had previously suffered in the automobile accident. When Mildred missed an NWA convention because of injuries, Wolfe told members that Burke was suffering from cancer and that her career was coming to an end. Eventually Burke and Wolfe divorced and through arbitration by the NWA board, they agreed that she would buy exclusive rights to the women’s title belt for $30,000.00 and that Wolfe would refrain from promoting women’s wrestling for a period of five years. Wolfe, however, had no intention of following through with this commitment and continued promoting, while looking for a way of supplanting Mildred as the new champion. With Wolfe being an NWA member and Burke prohibited from membership by virtue of her sex, the NWA allowed him to arrange a new tournament to crown a new women’s champion. Burke found out about the tournament and informed the Baltimore Sun that the results of the tournament had been decided and that Nell Stewart was going to be crowned the new champion. Embarrassed and painted into a corner, Wolfe switched plans and at the end of the tournament on June 14, 1953 in Baltimore, Maryland, June Byers pinned Nell Stewart to become the new Women’s World Champion. Burke thought otherwise, in that she had not actually lost the belt in a match and continued to call herself the champion.

Wolfe went to work immediately, marketing his new champion and getting her name out across the United States. She made appearances as a contestant on the popular games shows What’s My Line? and I’ve Got A Secret and got her covered in newspapers and magazines around the country. Burke wasn’t resting on her laurels, however. Mildred teamed with promoters Cowboy Luttrall and Don McIntyre and took a troupe of 13 female wrestlers based out of California and toured with them. Wolfe did the same with his group, with Byers and Stewart as his top stars. In addition, he badmouthed Mildred and her wrestlers every chance he got and dissuaded fellow promoters from booking her group. While many supported Burke and her claim to the titles, the NWA sided with their fellow member Wolfe. Thus, the world of women’s wrestling became a muddied ball of confusion and with Burke still having credibility across the United States, Wolfe sought a match to end the matter once and for all. After a year of negotiations, a match was set up on on August 20, 1954 in Atlanta, Georgia, pitting June Byers vs. Mildred Burke in a best 2 out of 3 falls contest.

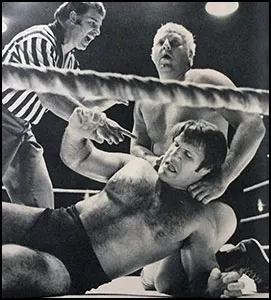

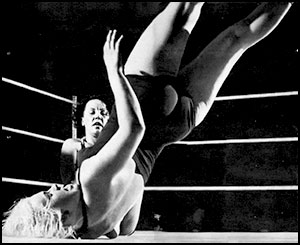

The match started with Byers holding the size advantage, but Burke had been undefeated for more than 17 years. Burke, however, had suffered a knee injury prior to the match and injured it again during the first fall, which went to Byers. Burke later said that it was dislocated and that she popped it back into place for the second fall. During the second fall, the two fought for another 47 minutes when the match was called off (presumably because Burke was unable to continue). In his book Queen of the Ring, author Jeff Lean says that the ring announcer declared “Commissioner stops the bout. Mildred Burke is still officially champion of the world.” However, Wolfe fed reports to news media throughout the country touting Byers victory, despite the fact that she failed to secure two falls. Byers argued strenuously on her own behalf. “Mildred claims she wasn’t defeated, but I pinned her in the first fall. During the second fall, she left the ring and refused to come back. Regardless of what she told people, it was a shoot.” Wolfe and Byers ultimately prevailed months later after persuading the Atlanta Athletic Commission to award Byers the title while Mildred was on tour in Japan.

After 17 years of the title being in the hands of Mildred Burke, June Byers was a fresh new face to wrestling fans across the United States and she wasn’t going to be just a transitional champion. She utilized her good looks and athletic figure to attract attention, but used her excellent technical wrestling skills to gain applause. More than anything, she was very tough in the ring and very rough with her opponents. She was very stiff with newcomers, testing them to see if they had what it took to be in the business. Ethel Brown remembered “My worst match was a match with June Byers when she purposely hit me in the face with her fist and broke my nose, blackened both my eyes and my face.” Although she did not dominate the sport or draw crowds the way that Burke did, June was a legitimate champion and helped to take the sport of women’s wrestling from the side show that it had often been, to a one of competitive matches and great showmanship.

In 1956, Byers suffered from some of the same backstabbing that enabled her to become champion as rumors began circulating that she planned to retire as the reigning champion. Northeastern NWA promoters, led by Vince McMahon, saw an opportunity to peddle women’s wrestling to their fans and wanted more control over the women’s champion. As a result, they influenced the Baltimore Athletic Commission to strip Byers of the title belt which allowed McMahon to stage a 13-woman battle royal on September 18, 1956 at the Baltimore Coliseum, with the Fabulous Moolah coming out on top over Judy Grable. Byers wasn’t relinquishing her crown that easily however, and continued to wrestle with the support of the majority of NWA promoters, and once again two women toured the country claiming to be the top woman wrestler. In 1960, when the American Wrestling Association was formed, it considered Byers to be the NWA reigning champion and therefore recognized her as the first AWA Women’s Champion (although she was later stripped of this title when she no-showed a title defense again Penny Banner).

When Wolfe died in 1963, his promotion fell apart and Byers moved to St. Louis, Missouri to work under promoters Sam Muchnick and Sam Meneker (whom she would eventually marry). Later that year, during a match, she was hit in the head by a Coca-Cola bottle and suffering from quadruple-vision, she collided with a tree while driving home. She sustained a leg injury so severe that it forced her to retire from the sport on January 1, 1964 (she continued to suffer from double-vision for much of the rest of her life). She returned to her hometown of Houston, Texas where she became a real estate agent. She remained married to Meneneker until his death in 1994. She had two children, but her son Billy died tragically from an electrocution accident and Judy was reported to have never recovered from the loss. She died at her home from pneumonia on July 20, 1998 at the age of 76. She left behind her daughter Jewel, four grandchildren and five great grandchildren.

When Wolfe died in 1963, his promotion fell apart and Byers moved to St. Louis, Missouri to work under promoters Sam Muchnick and Sam Meneker (whom she would eventually marry). Later that year, during a match, she was hit in the head by a Coca-Cola bottle and suffering from quadruple-vision, she collided with a tree while driving home. She sustained a leg injury so severe that it forced her to retire from the sport on January 1, 1964 (she continued to suffer from double-vision for much of the rest of her life). She returned to her hometown of Houston, Texas where she became a real estate agent. She remained married to Meneneker until his death in 1994. She had two children, but her son Billy died tragically from an electrocution accident and Judy was reported to have never recovered from the loss. She died at her home from pneumonia on July 20, 1998 at the age of 76. She left behind her daughter Jewel, four grandchildren and five great grandchildren.

She also left behind a legacy of greatness that is often overlooked. While the names Mildred Burke, Penny Banner and the Fabulous Moolah often overshadow hers, her contemporaries often sang her praises, with Banner calling her the “greatest champion ever.” She was the first woman to ever hold the Women’s World title and Women’s World Tag Team tiles at the same time. and was posthumously inducted into the Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame in 2006 and into the WWE Hall of Fame in 2017.

She also left behind a legacy of greatness that is often overlooked. While the names Mildred Burke, Penny Banner and the Fabulous Moolah often overshadow hers, her contemporaries often sang her praises, with Banner calling her the “greatest champion ever.” She was the first woman to ever hold the Women’s World title and Women’s World Tag Team tiles at the same time. and was posthumously inducted into the Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame in 2006 and into the WWE Hall of Fame in 2017.

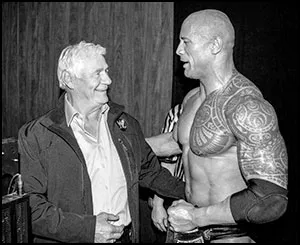

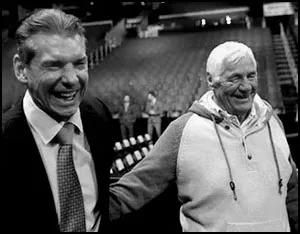

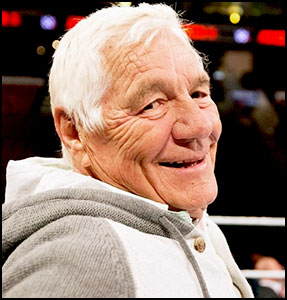

by Stephen Von Slagle

A man whose talent as a performer was nearly unrivaled and whose vision & skill behind the scenes truly helped change the business forever, there are few men who have been as influential during the modern era of professional wrestling than Pat Patterson. In terms of his ringwork, Patterson was clearly one of the premier workers in the sport during his (or any other) time. His sense of timing, realistic bumping and fluidity of moves placed him in an elite class of performer and his unique, believable style influenced both the wrestlers of his day and those who were yet to come. However, following his retirement from active competition after a career of more than twenty-five years, Pat Patterson went on to become even more influential as one of the main creative forces at WWE for more than two decades. Second only to Vince McMahon himself, Patterson is the man responsible for booking some of the most unique matches & memorable angles in World Wrestling Entertainment history.

During more than a quarter century as a professional wrestler, Patterson (along with several other ahead-of-their-time workers from his era) unquestionably elevated the state of the art through his innovative, precise and realistic ringwork. Once his career inside of the ring came to an end and he became part of the promotion’s management team, Patterson was widely regarded as a mentor to new talent and a master of laying out matches. Coming up with exciting, unique finishes and money-making angles, Patterson was a key figure in the WWF’s initial success during the Eighties, as well as the promotion’s meteoric rise during the Nineties. By virtue of his limited (and, at times, non-existent) on-air role, a casual viewer would have no clue as to the extent of influence Patterson has had on WWE over the years. But, make no mistake about it, World Wrestling Entertainment would be a completely different (and probably far less successful) company had Pat Patterson not been such an integral part of its creative team for so many years.

During more than a quarter century as a professional wrestler, Patterson (along with several other ahead-of-their-time workers from his era) unquestionably elevated the state of the art through his innovative, precise and realistic ringwork. Once his career inside of the ring came to an end and he became part of the promotion’s management team, Patterson was widely regarded as a mentor to new talent and a master of laying out matches. Coming up with exciting, unique finishes and money-making angles, Patterson was a key figure in the WWF’s initial success during the Eighties, as well as the promotion’s meteoric rise during the Nineties. By virtue of his limited (and, at times, non-existent) on-air role, a casual viewer would have no clue as to the extent of influence Patterson has had on WWE over the years. But, make no mistake about it, World Wrestling Entertainment would be a completely different (and probably far less successful) company had Pat Patterson not been such an integral part of its creative team for so many years.

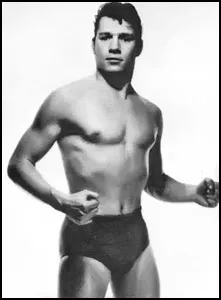

Pat Patterson was born Pierre Clermont on January 19, 1941 in Montreal, Quebec and began his professional wrestling career in 1958 while still a teenager, spending his first few years in the business learning, improving and paying his share of dues while slowly working his way up the card. His first bookings in the U.S. took place in Boston, working for the legendary Tony Santos in 1962 before moving on to Don Owen’s Oregon-based territory later that same year. By the mid Sixties, the talented young French Canadian had matured into a very capable & respected worker and he eventually began to amass a collection of championship victories. Wrestling as “Pretty Boy” Pat Patterson, his first title win came on June 17, 1964 when he teamed with “Tough” Tony Borne to win the Pacific Northwest Tag Team championship. During his stay in the territory, Patterson also wore the region’s top singles belt, the NWA Pacific Northwest Heavyweight title, on three occasions between 1964-1966.

Pat Patterson was born Pierre Clermont on January 19, 1941 in Montreal, Quebec and began his professional wrestling career in 1958 while still a teenager, spending his first few years in the business learning, improving and paying his share of dues while slowly working his way up the card. His first bookings in the U.S. took place in Boston, working for the legendary Tony Santos in 1962 before moving on to Don Owen’s Oregon-based territory later that same year. By the mid Sixties, the talented young French Canadian had matured into a very capable & respected worker and he eventually began to amass a collection of championship victories. Wrestling as “Pretty Boy” Pat Patterson, his first title win came on June 17, 1964 when he teamed with “Tough” Tony Borne to win the Pacific Northwest Tag Team championship. During his stay in the territory, Patterson also wore the region’s top singles belt, the NWA Pacific Northwest Heavyweight title, on three occasions between 1964-1966.

During this same time period, Patterson wrestled throughout the southwest, most notably in the NWA’s Amarillo territory, which was operated by the renowned Funk family. While competing in Texas, Patterson quickly established himself as a top heel and eventually won the territory’s main belt, the NWA North American title, on October 24, 1968 by defeating Pat O’Connor. Additionally, Patterson enjoyed a run as the Texas Brass Knuckles champion and participated in a lengthy feud against the legendary Dory Funk, Sr. and his talented sons Dory, Jr. and Terry.

During this same time period, Patterson wrestled throughout the southwest, most notably in the NWA’s Amarillo territory, which was operated by the renowned Funk family. While competing in Texas, Patterson quickly established himself as a top heel and eventually won the territory’s main belt, the NWA North American title, on October 24, 1968 by defeating Pat O’Connor. Additionally, Patterson enjoyed a run as the Texas Brass Knuckles champion and participated in a lengthy feud against the legendary Dory Funk, Sr. and his talented sons Dory, Jr. and Terry.

With several years of experience in the business now to his credit, it was during his lengthy stay in Roy Shire’s San Francisco territory that the talented Patterson truly came into his own as a top-level competitor. Whether working as a beloved babyface or a hated heel, Patterson excelled at eliciting the desired response from his audience while delivering consistently outstanding matches against a variety of opponents. Indeed, outside of Ray “The Crippler” Stevens, there had never been a more popular babyface or hated heel than Pat Patterson to compete in the popular San Francisco promotion. Consequently, Patterson was responsible for countless sell-outs of the territory’s premier venue, the legendary Cow Palace. Given his level of popularity, it’s no surprise that Patterson captured the coveted NWA United States Heavyweight championship (the territory’s top prize) no less than six different times between 1969-1977 by defeating opponents such as Rocky “Soul Man” Johnson, Mr. Fuji, The Great Mephisto, Bugsy McGraw, Alexis Smirnoff and Angelo “King Kong” Mosca.

In addition to being one of the most successful singles performers of his day, Patterson was also one-half of some truly formidable, top-level tag teams and he won numerous championships with a variety of different partners. Included among his many accomplishments in the tag division are two NWA Pacific Northwest Tag team titles (with Tony Borne and The Hangman, both in 1964) and one IWA World Tag Team title (with Art Nelson in 1967).

As far as the San Francisco territory is concerned, Pat Patterson won the prestigious NWA World Tag Team championship on eleven different occasions with diverse partners such as Billy Graham, Ray Stevens, Pedro Morales, Pepper Gomez, Peter Maivia, “Moondog” Lonnie Mayne, Peter Maivia and Tony Garea. Patterson also went on to capture the Florida Tag Team title with Ivan Koloff in 1977 and, along with Stevens, the AWA World Tag Team title in 1978. In Los Angeles, he teamed with Johnny Powers to win the NWA North American Tag Team title in 1973 while back home in Quebec, Patterson scored five separate Canadian International Tag Team championships (two with Ray Rougeau and three with Pierre Lefevre).

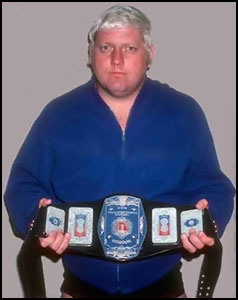

In terms of the singles ranks, Pat Patterson continued to be one of the most prolific champions of the day, despite never winning “the big one” (i.e. the NWA, AWA or WWF World Heavyweight title) and he captured several of the top regional titles as the decade came to a close, including the Florida Heavyweight title in 1977, the NWA Americas championship and, under the tutelage of the Grand Wizard of Wrestling, the WWF North American title in 1979. In September of 1979, after the WWF had made the decision to retire the North American title and replace it with a different secondary title, Patterson again made history by becoming the inaugural WWF Intercontinental champion. He went on to hold the new title belt for over a half-year and established the new championship as a legitimate prize that was second only to the WWF Heavyweight title before eventually losing the IC belt to former Olympic weightlifter Ken Patera. Along the way, Patterson transformed himself from one of the Federation’s most hated ring villains to a beloved fan favorite. After losing the Intercontinental title, and following a twenty-year career in the ring, Patterson slowly made the transition from active competitor to color commentator, a position that he maintained for the first few years of the 1980s. While serving as lead announcer Vince McMahon’s knowledgeable color commentator, the retired legend still occasionally became involved in the action, most notably during a very memorable series against Sgt. Slaughter.

In terms of the singles ranks, Pat Patterson continued to be one of the most prolific champions of the day, despite never winning “the big one” (i.e. the NWA, AWA or WWF World Heavyweight title) and he captured several of the top regional titles as the decade came to a close, including the Florida Heavyweight title in 1977, the NWA Americas championship and, under the tutelage of the Grand Wizard of Wrestling, the WWF North American title in 1979. In September of 1979, after the WWF had made the decision to retire the North American title and replace it with a different secondary title, Patterson again made history by becoming the inaugural WWF Intercontinental champion. He went on to hold the new title belt for over a half-year and established the new championship as a legitimate prize that was second only to the WWF Heavyweight title before eventually losing the IC belt to former Olympic weightlifter Ken Patera. Along the way, Patterson transformed himself from one of the Federation’s most hated ring villains to a beloved fan favorite. After losing the Intercontinental title, and following a twenty-year career in the ring, Patterson slowly made the transition from active competitor to color commentator, a position that he maintained for the first few years of the 1980s. While serving as lead announcer Vince McMahon’s knowledgeable color commentator, the retired legend still occasionally became involved in the action, most notably during a very memorable series against Sgt. Slaughter.

Meanwhile, behind the scenes, Patterson’s role as an agent and member of the WWF creative team grew as the regional group underwent its remarkable transformation into a national (and then worldwide) promotion. Following one of the most successful careers in professional wrestling history, the highly talented Pat Patterson officially retired from the ring in 1984. As an agent for the next several years, Patterson used his vast experience and knowledge to help lay out classic bouts for the Federation’s top performers. At the same time, he served as a booking assistant for Vince McMahon, helping greatly with the creative direction of the WWF during its mid Eighties explosion in popularity. In what history has shown to be perhaps his longest-lasting contribution to WWE, Patterson created The Royal Rumble in 1988 and personally booked the popular annual specialty match throughout the majority of its existence.

Meanwhile, behind the scenes, Patterson’s role as an agent and member of the WWF creative team grew as the regional group underwent its remarkable transformation into a national (and then worldwide) promotion. Following one of the most successful careers in professional wrestling history, the highly talented Pat Patterson officially retired from the ring in 1984. As an agent for the next several years, Patterson used his vast experience and knowledge to help lay out classic bouts for the Federation’s top performers. At the same time, he served as a booking assistant for Vince McMahon, helping greatly with the creative direction of the WWF during its mid Eighties explosion in popularity. In what history has shown to be perhaps his longest-lasting contribution to WWE, Patterson created The Royal Rumble in 1988 and personally booked the popular annual specialty match throughout the majority of its existence.

As the WWF experienced its second wave of incredible popularity during the “Attitude Era” of the late Nineties, Patterson returned to Federation storylines with Gerald Brisco, forming the entertaining comedic heel duo known collectively as The Stooges. While he later admitted that he was not particularly fond of the role, the two beguiling veterans, each trying his best to out-do the other in order to become Mr. McMahon’s favorite lackey, was a guilty pleasure of WWF fans and a surprisingly consistent ratings draw for Federation television programming. The bumbling, stumbling Stooges were an ancillary part of several very important and successful storylines involving McMahon adversaries such as “Stone Cold” Steve Austin, The Rock and The Undertaker, among others.

After retiring from his backstage creative duties in the Fall of 2004, Patterson did continue to make occasional onscreen appearances, although they were few and far between. Additionally, as a creative consultant, he helped shape WWE content long after he’d officially left his day-to-day duties within the business.

After retiring from his backstage creative duties in the Fall of 2004, Patterson did continue to make occasional onscreen appearances, although they were few and far between. Additionally, as a creative consultant, he helped shape WWE content long after he’d officially left his day-to-day duties within the business.

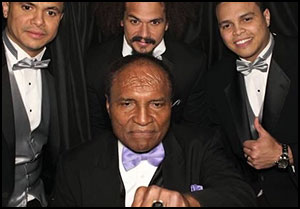

As an openly gay man in the oftentimes conservative world of professional wrestling during the Sixties and Seventies, Patterson surely faced his share of discrimination. However, his talent and good character often won over those who were prejudiced against his lifestyle. And, although Patterson’s sexuality was not openly discussed on television, it was occasionally alluded to in a tongue-in-cheek manner by announcers and co-workers.  Then, some 56 years after his pro wrestling debut, the not-so-secret status of Patterson’s personal life was finally addressed publicly on a 2014 episode of the WWE Network’s “Legends’ House” program. During the 2014 season finale of the series, Patterson came out to the world, discussing his experiences as a gay pro wrestler and his forty-year partnership with Louie Dondero, who passed away in 1998. Two years later, Patterson further addressed the topic (along with many others) when he released his critically acclaimed autobiography, Accepted: How the First Gay Superstar Changed WWE in August of 2016.

Then, some 56 years after his pro wrestling debut, the not-so-secret status of Patterson’s personal life was finally addressed publicly on a 2014 episode of the WWE Network’s “Legends’ House” program. During the 2014 season finale of the series, Patterson came out to the world, discussing his experiences as a gay pro wrestler and his forty-year partnership with Louie Dondero, who passed away in 1998. Two years later, Patterson further addressed the topic (along with many others) when he released his critically acclaimed autobiography, Accepted: How the First Gay Superstar Changed WWE in August of 2016.

Pat Patterson was honored by the Cauliflower Alley Club in 1995 and is a member of the WWE Hall of Fame (1996), the Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Fame (1996) and the Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame (2006).

On November 27, 2020, Patterson, who had been battling cancer for several years, was rushed to the hospital and treated for a blood clot in his liver. On December 2, 2020, Pierre “Pat Patterson” Clermont passed away in Miami, Florida.

by Stephen Von Slagle

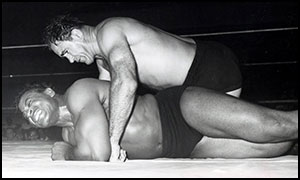

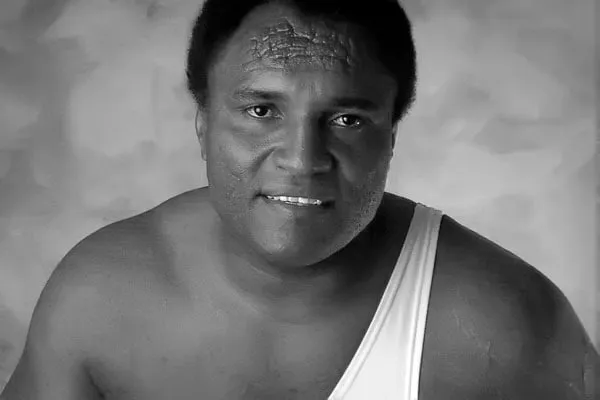

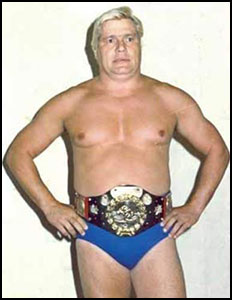

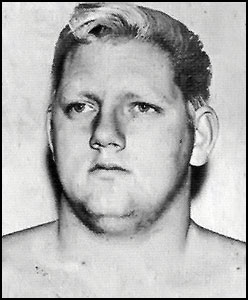

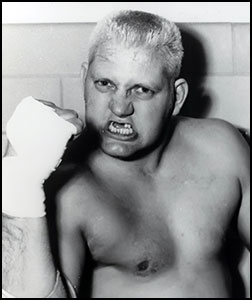

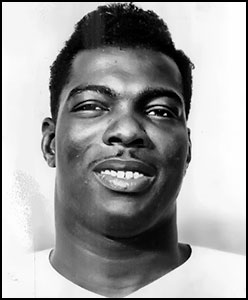

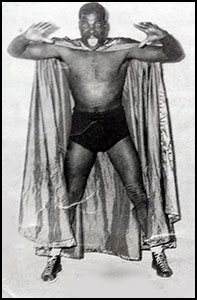

Although he never carried the World Heavyweight title belt, nor was his level of mainstream fame on par with that of the biggest stars in pro wrestling history, there is little question that Dick Murdoch was one of the most successful and important wrestlers in the sport during his thirty-year career. Additionally, there is no doubt that, in the ring, he was one of the most talented. His mixture of traditional brawling, an impressive array of scientific maneuvers and flawless timing combined with a natural talent on the microphone put Murdoch several notches above most others and into an elite level of workers. Due to the nature of wrestling’s territorial structure during the time he spent in the business, Murdoch (like all wrestlers of his era) lived a nomadic life, constantly moving from region to region, never staying too long in one place and, as a result, by the time he had reached his fifth year in the sport, he’d already competed in a dozen separate promotions across the country and internationally. Whether he performed as a heel or babyface, in a tag team or as a singles wrestler, doing comedy bits or blood & guts brawling, the highly talented second-generation star was able to adapt and excel in any given situation.

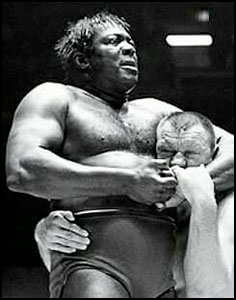

Dick Murdoch was born Hart Richard Murdoch on August 16, 1946 in Waxahachie, Texas. The stepson of Frankie Hill Murdoch (and the nephew of Texas legend “Farmer” Jones) Dick Murdoch grew up in the wrestling business and followed his dad into the sport after being trained by Bob Geigel and Pat O’Connor. Making his debut at the age of nineteen, Murdoch was a natural inside of the squared circle and was voted the 1965 NWA Rookie of the Year. In 1968, when he partnered with Dusty Rhodes (who had made his own pro debut less than a year earlier) and formed their now legendary tag team, The Texas Outlaws, the young duo soon moved on to their first major booking, the Central States territory. While wrestling in the Kansas City-based promotion, the young and belligerent Texas Outlaws quickly established themselves as the top heel tag team in the region and together they captured the area’s most prestigious championship, the NWA North American Tag Team title. Big, brawny, and not at all above taking an illegal shortcut to score a victory, when The Outlaws defeated Tom & Terry Martin to win the North American belts on November 7, 1968, it simply marked the first in a long list of championships that Murdoch & Rhodes would win together.

Dick Murdoch was born Hart Richard Murdoch on August 16, 1946 in Waxahachie, Texas. The stepson of Frankie Hill Murdoch (and the nephew of Texas legend “Farmer” Jones) Dick Murdoch grew up in the wrestling business and followed his dad into the sport after being trained by Bob Geigel and Pat O’Connor. Making his debut at the age of nineteen, Murdoch was a natural inside of the squared circle and was voted the 1965 NWA Rookie of the Year. In 1968, when he partnered with Dusty Rhodes (who had made his own pro debut less than a year earlier) and formed their now legendary tag team, The Texas Outlaws, the young duo soon moved on to their first major booking, the Central States territory. While wrestling in the Kansas City-based promotion, the young and belligerent Texas Outlaws quickly established themselves as the top heel tag team in the region and together they captured the area’s most prestigious championship, the NWA North American Tag Team title. Big, brawny, and not at all above taking an illegal shortcut to score a victory, when The Outlaws defeated Tom & Terry Martin to win the North American belts on November 7, 1968, it simply marked the first in a long list of championships that Murdoch & Rhodes would win together.

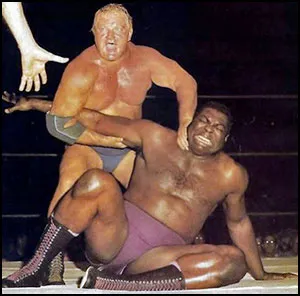

Next on that title list was Detroit’s prestigious version of the NWA World Tag championship, which The Outlaws won by defeating the team of Ben Justice & The Stomper on March 21, 1970. The rule breaking Texans immediately became two of the most hated performers ever to compete in the small but profitable territory and they enjoyed a lengthy reign as heel champions in the Motor City. Eventually, though, the popular team of Bobo Brazil & Lord Athol Layton ended their reign by upending the Texas Outlaws before a capacity crowd at Detroit’s Cobo Hall on August 8, 1970. After dropping the NWA World Tag Team title, the team of Murdoch & Rhodes moved on to their next booking, which turned out to be the Alliance’s Florida circuit. Immediately upon their arrival in the Sunshine State, the rugged, wild Outlaws stormed through their competition until they’d established themselves as the number one contenders for the region’s top Tag Team gold, the Florida Tag Team championship. Less than a month after their Florida debut, the talented young duo defeated reigning champions Jose Lothario & Argentina Apollo on September 17, 1970 in Jacksonville, Florida to capture the belts Yet, true to form, the hated Texans were stripped of their Florida Tag Team belts in December of 1970 following a particularly controversial storyline incident that led to their departure from the territory.

Next on that title list was Detroit’s prestigious version of the NWA World Tag championship, which The Outlaws won by defeating the team of Ben Justice & The Stomper on March 21, 1970. The rule breaking Texans immediately became two of the most hated performers ever to compete in the small but profitable territory and they enjoyed a lengthy reign as heel champions in the Motor City. Eventually, though, the popular team of Bobo Brazil & Lord Athol Layton ended their reign by upending the Texas Outlaws before a capacity crowd at Detroit’s Cobo Hall on August 8, 1970. After dropping the NWA World Tag Team title, the team of Murdoch & Rhodes moved on to their next booking, which turned out to be the Alliance’s Florida circuit. Immediately upon their arrival in the Sunshine State, the rugged, wild Outlaws stormed through their competition until they’d established themselves as the number one contenders for the region’s top Tag Team gold, the Florida Tag Team championship. Less than a month after their Florida debut, the talented young duo defeated reigning champions Jose Lothario & Argentina Apollo on September 17, 1970 in Jacksonville, Florida to capture the belts Yet, true to form, the hated Texans were stripped of their Florida Tag Team belts in December of 1970 following a particularly controversial storyline incident that led to their departure from the territory.

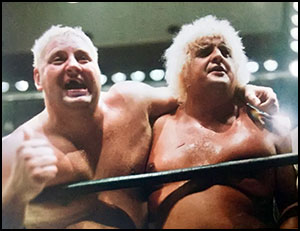

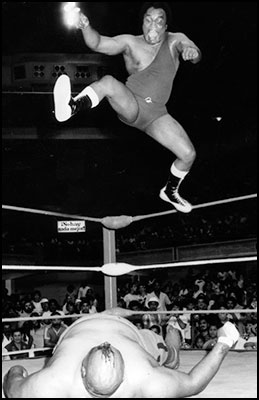

After their successful run in Florida concluded, Murdoch and Rhodes entered Australia’s IWA, where they immediately captured the promotion’s World Tag Team title by defeating the popular team of Mark Lewin & Mario Milano on January 21, 1971 in Sydney. Over the course of the following three months, The Texas Outlaws ruled over the tag division in the Land Down Under and ran roughshod over every team placed before them. That is, of course, until they came up against Mark Lewin and his new partner, the legendary Killer Kowalski, who teamed together to defeat Murdoch & Rhodes in March of 1971. Back in the States, The Texas Outlaws enjoyed a very lengthy and prosperous run in the Minneapolis-based American Wrestling Association. Despite the fact that they never wore the AWA World Tag Team title, the rugged team was incredibly successful, drawing large crowds who paid to see the cheating Texans finally receive their just rewards. With that in mind, it’s no surprise that during the early Seventies, the hated combo proved to be excellent, long-running opponents for the promotion’s top tandem, the beloved blue-collar duo of Dick the Bruiser & The Crusher. Still, in the months following their high-profile run in the AWA (and after a half-decade as a team) Murdoch and Rhodes, two highly talented and charismatic individuals, made the decision to break up their very successful partnership in order to explore opportunities in the singles division.

Yet, over the ensuing decade, the two would reform their famed team on several occasions, most notably in the Florida, Georgia and Mid-South promotions. Although their infrequent reunions were always hugely successful, there was also big money in fans seeing the two best friends squaring off against each other. With a storyline scenario that depicted a bitter Murdoch as being jealous of the incredible success and fan support enjoyed by “The American Dream” after they originally parted ways, the two longtime friends & partners engaged in a very dramatic, intense and bloody feud. Still, in the end, The Texas Outlaws, one of the greatest teams of their era, would eventually mend their damaged friendship and reunite, much to the delight of their fans. Despite the fact that Rhodes is, by far, the partner that Murdoch was most associated with during this time period, the highly skilled 6’4″ scientific brawler also occasionally teamed with other wrestlers during the early portion of his career. For instance, twice in 1969 he paired up with K.O. Kox (better known to Seventies-era fans as “Bruiser” Bob Sweetan) to capture the NWA North American Tag Team title. Murdoch also teamed with another large yet very skilled Texan, “Big, Bad” Bobby Duncum, to win the Florida Tag Team championship in September of 1971 as well as the NWA Western States Tag Team title in 1972. Additionally, Murdoch captured the NWA U.S. Tag title (Tri State version) with Killer Karl Kox in the Fall of 1975.

Yet, over the ensuing decade, the two would reform their famed team on several occasions, most notably in the Florida, Georgia and Mid-South promotions. Although their infrequent reunions were always hugely successful, there was also big money in fans seeing the two best friends squaring off against each other. With a storyline scenario that depicted a bitter Murdoch as being jealous of the incredible success and fan support enjoyed by “The American Dream” after they originally parted ways, the two longtime friends & partners engaged in a very dramatic, intense and bloody feud. Still, in the end, The Texas Outlaws, one of the greatest teams of their era, would eventually mend their damaged friendship and reunite, much to the delight of their fans. Despite the fact that Rhodes is, by far, the partner that Murdoch was most associated with during this time period, the highly skilled 6’4″ scientific brawler also occasionally teamed with other wrestlers during the early portion of his career. For instance, twice in 1969 he paired up with K.O. Kox (better known to Seventies-era fans as “Bruiser” Bob Sweetan) to capture the NWA North American Tag Team title. Murdoch also teamed with another large yet very skilled Texan, “Big, Bad” Bobby Duncum, to win the Florida Tag Team championship in September of 1971 as well as the NWA Western States Tag Team title in 1972. Additionally, Murdoch captured the NWA U.S. Tag title (Tri State version) with Killer Karl Kox in the Fall of 1975.

Despite his many accomplishments in the tag team ranks, Dick Murdoch also proved himself to be a very successful champion in the singles division, even during the early portion of his career when he was still relatively inexperienced. One of his first singles championships came in the form of the Central States Heavyweight title, which he won on February 28, 1969 in St. Joseph, Missouri. The young and talented big man went on to enjoy a surprisingly long reign atop the Central States territory before finally losing his title to former NWA World champion (and one of the men who trained him several years earlier) Pat O’Connor on June 20, 1969. Then, in 1970 (and once again in 1972) Murdoch became the Texas Brass Knucks champion, followed by two lengthy reigns in Florida as the NWA Southern Heavyweight champion during 1971.

By 1974, Murdoch had returned to West Texas, specifically the Funk’s Amarillo-based promotion, where the young star continued his winning ways. While competing in the region, he captured the NWA Western States title as well as twice winning the International Heavyweight title. Some six years later, in 1980, Murdoch would partner with Bob Windham (Blackjack Mulligan) in an attempt to enter the lucrative world of promotional ownership by purchasing the Amarillo territory from the Funk brothers. However, while they did have some initial success in reviving the dying promotion, in the end, the monetary losses were simply too great to continue on.

By 1974, Murdoch had returned to West Texas, specifically the Funk’s Amarillo-based promotion, where the young star continued his winning ways. While competing in the region, he captured the NWA Western States title as well as twice winning the International Heavyweight title. Some six years later, in 1980, Murdoch would partner with Bob Windham (Blackjack Mulligan) in an attempt to enter the lucrative world of promotional ownership by purchasing the Amarillo territory from the Funk brothers. However, while they did have some initial success in reviving the dying promotion, in the end, the monetary losses were simply too great to continue on.

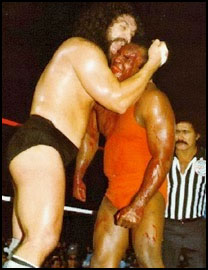

Bill Watts’ neighboring Mid-South Wrestling promotion was a territory filled with some of the biggest, meanest and, most importantly to Watts, the toughest wrestlers of the day. So, naturally, the six-four, two hundred and seventy pound Murdoch fit into Watts’ style of wrestling & promoting quite well and he achieved great levels of success while competing in the rugged multi-state territory. Between 1977-1978, the talented big man captured the region’s most prestigious championship, the NWA North American title, on three different occasions by defeating the likes of top Mid-South competitors such as Waldo Von Erich, Bill Watts and Jerry Oates. Always at the center of controversy, Murdoch, who was as adept at delivering entertaining interviews as he was at performing inside the ring, established himself as one of the Mid-South promotion’s top wrestlers during the late Seventies and he would go on to enjoy that status in the territory for many years to come.

Another top promotion in which the brawny Texan excelled was the NWA’s legendary St. Louis group, which was owned by longtime NWA President Sam Muchnick. Rich in history and tradition, wrestling skill and the ability to perform in the ring was what determined success or failure in Muchnick’s company, not outlandish gimmicks or controversial, envelope-pushing angles. Although his colorful interviews were as entertaining as nearly any one else’s, Dick Murdoch was also very much a no-frills type of competitor who didn’t waste time acclimating himself to the St. Louis promotion. On February 26, 1978, Murdoch met and defeated his former Tri-State tag team partner Ted Dibiase to win his first of three Missouri Heavyweight championships. Following his title victory, Murdoch went on to rule over the region for nearly six months before finally dropping the Missouri title to the legendary brawler Dick the Bruiser. Murdoch and The Bruiser, who had feuded throughout the AWA earlier in the decade when Murdoch was a Texas Outlaw, continued their violent series with great success at the box-office. Then, eight months after losing the championship to The Bruiser, Murdoch regained the Missouri title from his tough-as-nails rival in a match held at The Kiel Auditorium. However, their intense feud was far from over, and Dick the Bruiser eventually rebounded, winning the prestigious title back from Murdoch two months later on March 18, 1979. Despite once again losing the title to The Bruiser, Murdoch remained a top performer in the promotion and the champion’s number one contender. After trading title victories back and forth, Murdoch got the last laugh when he once again took the Missouri title from Dick the Bruiser, this time on July 13, 1979.

After his long-running program with The Bruiser finally concluded, Murdoch continued to defend his Missouri title against the region’s top competitors before finally losing the important championship to Kevin Von Erich on November 23, 1979. A few months later, Murdoch re-entered the neighboring Central States promotion, this time as a fan favorite, and promptly teamed with “Bulldog” Bob Brown to win the Central States Tag Team title by defeating the formidable duo of Ernie “The Big Cat” Ladd & Bruiser Brody on March 20, 1980 in Kansas City, Kansas.

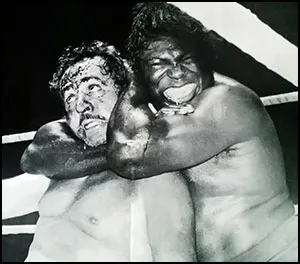

1980 was also the year that Murdoch began competing in the NWA’s Georgia Championship Wrestling promotion. Since the territory’s television programs were broadcast nationally via TBS, the NWA’s Georgia promotion was the most widely seen wrestling group in the world at that time and the only territory fortunate enough to have a national outlet. As a result, the top stars in the Georgia territory were, by extension, the top stars in the entire country. Having traveled throughout the territorial structure for years, Murdoch had already built up a very solid reputation across the country when he entered the Georgia promotion, and once there, he cemented his position as one of the biggest stars in the entire sport. Calling himself “Captain Redneck,” Dick Murdoch enjoyed a hugely successful run as one of the talent-rich Georgia territory’s most beloved fan favorites. Indeed, the charismatic tobacco-chewing, beer-swilling, working-class patriot genuinely ascended to impressive new heights of popularity during this period, especially when he entered into a bitter and violent main-event feud with the hated Iranian rulebreaker known as The Iron Sheik.

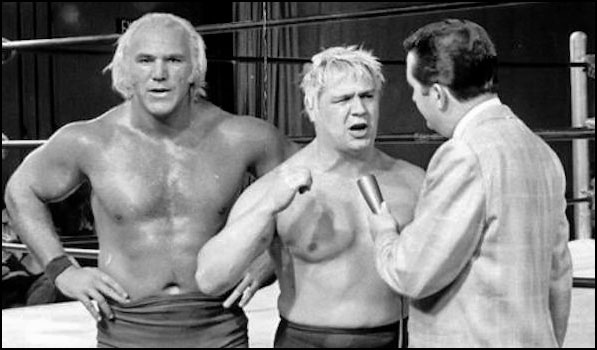

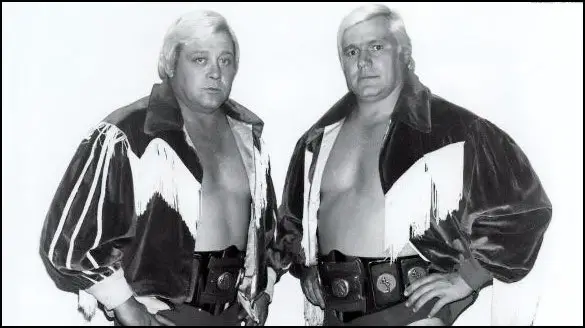

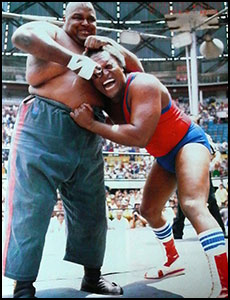

Following his highly successful stint in Georgia, he returned to Bill Watts’ Mid South promotion, where he was greeted by the region’s fans with a hero’s welcome. Almost immediately, “Captain Redneck” Dick Murdoch became involved in the Mid-South title picture and after forming a “dream team” with the mega-popular Junkyard Dog, he and JYD twice captured the Mid-South Tag Team championship in 1981. However, when he entered the World Wrestling Federation in the early Eighties, it was not as the popular “Captain Redneck” but rather as the rule-breaking Dick Murdoch of old. Although he never captured the Federation’s top prize, the wily veteran proved to be a major threat to Bob Backlund’s reign as the WWF titleholder, and the villainous Murdoch proved that he could truly work ‘both sides of the fence’ on a main-event level, with equally profitable results. Following a successful run in the WWF’s singles ranks, Murdoch, who had been one-half of some legitimately great tag teams, formed another championship-caliber duo early in 1984, this time with the talented New York street thug known as “The Golden Boy” Adrian Adonis.

Adrian Adonis had gained fame in both the AWA and WWF as part of the “East-West Connection” with former partner Jesse Ventura. Now teamed with the brawny Texan, he and Murdoch formed the “North-South Connection” and the two scientific brawlers immediately gelled into one of the most impressive rule-breaking tag teams in years. On April 17, 1984, the North-South Connection defeated the popular team of Tony Atlas & Rocky Johnson (known as The Soul Patrol) to capture the coveted World Wrestling Federation Tag Team championship in Hamburg, PA. Individually, Murdoch and Adonis were already incredibly gifted both as brawlers and as ring workers, however, when they combined their talents, the result was a finely-tuned wrestling machine that was unquestionably the all-around best tag team in the Federation at that time. Over the course of the following nine months, the North-South Connection of Dick Murdoch & Adrian Adonis ruled over the WWF’s tag team ranks at a time when the popularity of the promotion was literally exploding. However, in the months just prior to the tidal wave of momentum leading to the first-ever WrestleMania card, the North-South Connection dropped their WWF Tag Team championship belts to the up-and-coming young babyface team of Barry Windham & Mike Rotunda, who were known as the U.S. Express. Not long after the title loss, the nomadic Murdoch once again moved on to the next booking, which turned out to be his old stomping grounds in the Mid-South territory.

Still a couple of years away from launching its own national expansion as the Universal Wrestling Federation, Murdoch returned to a very exciting and talent-rich Mid South Wrestling Association. He did so, incidentally, as a babyface and the return of “Captain Redneck” Dick Murdoch was extremely well-received by M.S.W.A. fans. Not surprisingly, Murdoch soon captured the promotion’s premier championship, the North American Heavyweight title, on August 10, 1985 by defeating The Nightmare in New Orleans. Soon after becoming the North American champion, Murdoch disposed of the challenge posed by the former champion and then became involved in a highly intense feud with the hated “Hacksaw” Butch Reed. The powerful Reed had once been among the most popular wrestlers in the promotion, however, by the time he squared off against Captain Redneck, the former NFL star was about as hated as a wrestler can get. Finally, after close to two months of bloody, violent battles, Reed eventually toppled his popular rival to capture Murdoch’s North American title on October 14, 1985.

Still a couple of years away from launching its own national expansion as the Universal Wrestling Federation, Murdoch returned to a very exciting and talent-rich Mid South Wrestling Association. He did so, incidentally, as a babyface and the return of “Captain Redneck” Dick Murdoch was extremely well-received by M.S.W.A. fans. Not surprisingly, Murdoch soon captured the promotion’s premier championship, the North American Heavyweight title, on August 10, 1985 by defeating The Nightmare in New Orleans. Soon after becoming the North American champion, Murdoch disposed of the challenge posed by the former champion and then became involved in a highly intense feud with the hated “Hacksaw” Butch Reed. The powerful Reed had once been among the most popular wrestlers in the promotion, however, by the time he squared off against Captain Redneck, the former NFL star was about as hated as a wrestler can get. Finally, after close to two months of bloody, violent battles, Reed eventually toppled his popular rival to capture Murdoch’s North American title on October 14, 1985.

By the end of 1986, Murdoch had moved on to Jim Crockett’s National Wrestling Alliance, where he once again began competing as a “bad guy,” a role at which he truly excelled. Along with his new partner, the hated “Russian Bear” Ivan Koloff, Murdoch captured the NWA United States Tag Team title by defeating Ron Garvin & Barry Windham on March 14, 1987 in at Atlanta, Georgia. The rugged veteran duo held the belts for nearly a month before being stripped of the championship following a storyline incident which led to Murdoch being briefly suspended from the promotion.

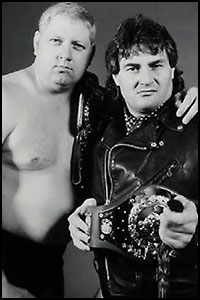

In the months following the sale of the NWA from the Crockett family to Ted Turner, Dick Murdoch once again revived his popular Captain Redneck gimmick and returned to the NWA, engaging in a semi-main event feud with the talented Bob Orton, Jr. as the decade closed. Another Dick Murdoch tag team of note was the “Hardline Collection Agency,” which he formed with Dick Slater in 1991. The Hardliners feuded in WCW with Rick and Scott Steiner, more than holding their own against the powerful & talented young duo.

Murdoch had also begun working full-time in Puerto Rico by the early Nineties, competing for the San Juan-based World Wrestling Council. While wrestling in the WWC (once again as a heel) Murdoch held several championships and enjoyed a very successful run as one of the promotion’s top villains. On November 23, 1991 he defeated TNT (a.k.a. Savio Vega) to win the WWC World TV title in Arroyo, PR. Just over a month later he lost the championship to Invader #1, however, the brawny Texan rebounded and soon regained the WWC World TV title early in 1992. From there, Murdoch went on to hold the prestigious championship for a full year. Even more importantly, the talented brawler captured the region’s top prize, the WWC Universal Heavyweight title, by defeating his masked nemesis, the Invader.

Following his run in the World Wrestling Council, Murdoch returned to the site of some of his greatest matches and fame, the island nation of Japan. This time, however, it was not with All Japan Pro Wrestling, where he traded the prestigious United National championship back and forth with the legendary Jumbo Tsuruta in 1980. Nor did Murdoch return to New Japan Pro Wrestling, where he was one of the premier gaijins for nearly a decade during the Eighties. To the surprise of many Japanese observers, Murdoch began competing for independent young Japanese leagues, particularly, the W*ING promotion.

The upstart hardcore league shared a talent exchange agreement with the WWC and was able to recruit the services of Murdoch, who was one of the most famous and respected American wrestlers in the country. Meanwhile, back in the States, he made several high-profile appearances on shows promoted by the newly revived National Wrestling Alliance as he slowly made the transition to a state of semi-retirement. After greatly reducing his wrestling schedule, Murdoch began taking on appearances in rodeos, doing celebrity bull roping. Around the same time period, he was offered, and accepted, a position with the Coors Brewing Company as a type of product ambassador & consultant.

Dick Murdoch was ranked #96 in Pro Wrestling Illustrated’s Top 500 Wrestlers of the P.W.I. Years (2003) and is also a member of the St. Louis Wrestling Hall of Fame (2010) and the Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame (2013).

On June 15, 1996, Hart Richard “Dick” Murdoch suffered a heart attack and passed away at the age of 49.

by Mark Long

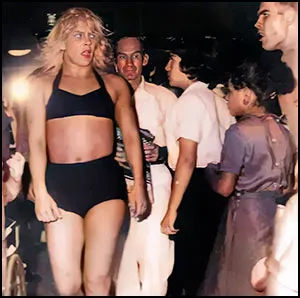

In the heyday of women’s wrestling, matches were filled with exciting action, but the top stars were either women with good looks and only passable wrestling skills or rough and tumble performers who were not that much to look at. Until Penny Banner. Banner brought a mixture of sound technical wrestling prowess and the persona of a Hollywood bombshell. A tremendous athlete and natural show woman, she is remembered by many as one of the top female wrestlers in the history of the sport.

Penny Banner was born Mary Ann Kostecki on August 11, 1934. She was the oldest child of Casimir Kostecki, a polish-born immigrant who worked at a shoe company and sold candy on the side, and Clara, a homemaker. Mary Ann had two siblings and the family had a meager life without many luxuries such as a television set. The family seemed happy until Mary Ann’s father ran off with another woman, a few weeks before her mother gave birth to another child. Faced with the prospect of raising four children alone, 31 year Clara was forced to put the children into an orphanage, the St. Vincent De Paul Home for Children in North St Louis, Missouri, for nine months. As a teenager Mary Ann worked in a hamburger shop in order to help her mother with the bills, but was unfortunate enough to meet a 21 year old man who showed an interest in her and began showering her with attention. At some point he came to her home and forced her inside. She later found out that he was wanted by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and worked with the bureau to set him up. While at the movie theater with him, she went to get popcorn, at which time FBI agents descended upon him and secured the arrest. Furious, he screamed at her, threatening to make her pay one day for setting him up. She feigned ignorance of the arrest and even visited him in prison to assuage his suspicion of her. Years later, as she walked alone on the street, he appeared out of nowhere and grabbed her. In later interviews she implied that he sexually assaulted her, but was unable to physically hold her down. He then threatened to kill her parents if she told anybody.

Penny Banner was born Mary Ann Kostecki on August 11, 1934. She was the oldest child of Casimir Kostecki, a polish-born immigrant who worked at a shoe company and sold candy on the side, and Clara, a homemaker. Mary Ann had two siblings and the family had a meager life without many luxuries such as a television set. The family seemed happy until Mary Ann’s father ran off with another woman, a few weeks before her mother gave birth to another child. Faced with the prospect of raising four children alone, 31 year Clara was forced to put the children into an orphanage, the St. Vincent De Paul Home for Children in North St Louis, Missouri, for nine months. As a teenager Mary Ann worked in a hamburger shop in order to help her mother with the bills, but was unfortunate enough to meet a 21 year old man who showed an interest in her and began showering her with attention. At some point he came to her home and forced her inside. She later found out that he was wanted by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and worked with the bureau to set him up. While at the movie theater with him, she went to get popcorn, at which time FBI agents descended upon him and secured the arrest. Furious, he screamed at her, threatening to make her pay one day for setting him up. She feigned ignorance of the arrest and even visited him in prison to assuage his suspicion of her. Years later, as she walked alone on the street, he appeared out of nowhere and grabbed her. In later interviews she implied that he sexually assaulted her, but was unable to physically hold her down. He then threatened to kill her parents if she told anybody.

A few years later when she was 19 years old, she was working at a car dealership when she learned that one of her co-workers was getting divorced. She was asked to work as a governess for the couple’s three children and she accepted the position which paid her a wage, and also afforded her the use of the family car. This allowed her to drive to a second job at a nearby lounge. While working there one night, the tall blond gained the attention of a man in the crowd. He was told that she was a fitness trainee and could do 200 sit ups. In truth, out of fear of her assaulter, Mary Ann, who had played basketball and volleyball in high school, had taken up weightlifting and judo as a means of defending herself. The man, who claimed to be a representative of National Wrestling Alliance president Sam Muchnick, bet her $20 that she couldn’t really perform that many sit ups. Upon finishing her shift, she performed all 200 and collected her prize. She was also invited to meet Muchnick, and after meeting her, Sam offered to buy her a ticket to travel to Columbus, Ohio to train under women’s wrestling promoter Billy Wolfe for a salary of $50 per week.

A few years later when she was 19 years old, she was working at a car dealership when she learned that one of her co-workers was getting divorced. She was asked to work as a governess for the couple’s three children and she accepted the position which paid her a wage, and also afforded her the use of the family car. This allowed her to drive to a second job at a nearby lounge. While working there one night, the tall blond gained the attention of a man in the crowd. He was told that she was a fitness trainee and could do 200 sit ups. In truth, out of fear of her assaulter, Mary Ann, who had played basketball and volleyball in high school, had taken up weightlifting and judo as a means of defending herself. The man, who claimed to be a representative of National Wrestling Alliance president Sam Muchnick, bet her $20 that she couldn’t really perform that many sit ups. Upon finishing her shift, she performed all 200 and collected her prize. She was also invited to meet Muchnick, and after meeting her, Sam offered to buy her a ticket to travel to Columbus, Ohio to train under women’s wrestling promoter Billy Wolfe for a salary of $50 per week.

Wolfe was impressed with her and after only two weeks, he put her in her first match on July 29, 1954, a tag team victory with Gloria Barattini over Mae Young and Olga Zepeda at the Cloverleaf Sports Arena in Valley View, Ohio. (Other narratives say that her first match was against Kathy Branch using boots borrowed from Ella Waldek). After just a few more matches, she was told that she would be given an opportunity to wrestle for the NWA Women’s World Title against June Byers. Byers was a 10 year veteran, but the newcomer was able to hold her own and last ten minutes against the champion in the match held on October 2, at the Memorial Auditorium in Canton, Ohio.

By now she was wrestling under the name Penny Banner. “Penny” described how insignificant she felt as a newcomer from St. Louis and the name “Banner” was chosen because Charlton Heston played the role of Ed Bannon in the movie Arrowhead and resembled an old boyfriend that had broken her heart. She stood 5’ 8’ and weighed 160 lbs., so she had the size and strength to compete with veteran wrestlers. She learned to wrestle quickly and was noted for her athleticism, utilizing such moves as the dropkick and sunset flip. She was also a picturesque beauty with a dazzling figure and thus had all the trappings of a fan favorite “babyface.” However, she was anything but, preferring to “wrestle dirty” as the gorgeous “heel.” With fewer than 50 girls in the business of professional wrestling at the time, while the women were in demand, there were less opportunities to stay in one place, because female wrestling was seen mostly as a novelty. Thus, Banner made endless trips from town to town, throughout the United States and Canada

By now she was wrestling under the name Penny Banner. “Penny” described how insignificant she felt as a newcomer from St. Louis and the name “Banner” was chosen because Charlton Heston played the role of Ed Bannon in the movie Arrowhead and resembled an old boyfriend that had broken her heart. She stood 5’ 8’ and weighed 160 lbs., so she had the size and strength to compete with veteran wrestlers. She learned to wrestle quickly and was noted for her athleticism, utilizing such moves as the dropkick and sunset flip. She was also a picturesque beauty with a dazzling figure and thus had all the trappings of a fan favorite “babyface.” However, she was anything but, preferring to “wrestle dirty” as the gorgeous “heel.” With fewer than 50 girls in the business of professional wrestling at the time, while the women were in demand, there were less opportunities to stay in one place, because female wrestling was seen mostly as a novelty. Thus, Banner made endless trips from town to town, throughout the United States and Canada

After a few years of paying Wolfe 40% of her earnings, Banner left his group and moved to Tennessee to work for promoter Nick Gulas. In addition to catching the eye of wrestling fans, she attracted the attention of a famous area celebrity as well – singer Elvis Presley. A mutual friend offered Penny a ticket to see the star on January 1, 1956 at the Kiel Auditorium in St. Louis. The tickets were in the nosebleed section forcing Banner to buy a pair of binoculars, but her disappointment disappeared when a group of police officers escorted her from her seat to watch the rest of the concert backstage. After the show, Banner says that she went with Elvis to his hotel, spending the night “necking” with him. Over the next three years, Elvis came to see her wrestle several times and the two went on five dates, including a night at his Graceland mansion. Their romance was unable to overcome his enlistment into the U.S. Army and the two never saw one another again. As she explained in an interview with wrestling journalist Mike Mooneyham “I do not think either of us were serious about having any kind of relationship. Hell, I never even thought of having a picture taken with him. To me, he was just a guy and I was just a girl.”

She found her first real success wrestling for Stu Hart in his Calgary Stampede promotion in Calgary, Alberta. She teamed with Bonnie Watson, and after a successful run, Hart decided to make them the Canadian Women’s tag team champions in 1957, Banner’s first title victory. During this period of career she would specialize in tag team wrestling, holding the NWA Women’s World Tag Team Championship on three occasions, first teaming with Bonnie Watson on August 15, 1956 in Albuquerque, New Mexico, next with Betty Jo Hawkins in 1957 and Lorraine Johnson in 1958. In one of her tag matches (in October 1958), Banner, Lorraine Johnson, Kay Noble, and Laura Martinez fought their way outside of the ring and were charged by police for inciting a riot (all four pled not guilty and their fines were paid by the promoters because of the publicity it provided).

After several years in the business, she began dating Johnny Weaver, a former referee who debuted as a wrestler in 1957. The two were married in St. Louis in 1959, with their reception at the Claridge Hotel, where wrestling promoter Sam Muchnick had an office. Later that year the couple welcomed a daughter named Wendi.

The 1960’s were indeed a Banner time for Penny as she began to concentrate on her singles career. The face of women’s wrestling had changed with Mildred Burke’s retirement in 1956. June Byers now held the National Wrestling Alliance (NWA) Women’s title but had declared that she intended to retire as the champion and was subsequently stripped of the belt by the Baltimore Athletic Commission in 1956. The commission announced a 13 woman battle royal for the belt and the Fabulous Moolah was crowned the new champion. Byers was still recognized as the champion by the American Wrestling Association (AWA) after it split from the NWA, and Penny was chosen to challenge her for the newly created AWA Women’s title. Banner won her first singles title on November 25, 1960, capturing the NWA Southern Women’s Championship (Georgia version) and then grabbed the NWA Texas Women’s Championship on March 8, 1961, defeating Nell Stewart in Fort Worth, Texas. Byers, however, no-showed the event and promoter James Barnett decided that a nine woman battle royal would be held in Angola, Indiana to determine the new titleholder. Banner was the last woman standing at the end and was named the new AWA Women’s World Champion.

The 1960’s were indeed a Banner time for Penny as she began to concentrate on her singles career. The face of women’s wrestling had changed with Mildred Burke’s retirement in 1956. June Byers now held the National Wrestling Alliance (NWA) Women’s title but had declared that she intended to retire as the champion and was subsequently stripped of the belt by the Baltimore Athletic Commission in 1956. The commission announced a 13 woman battle royal for the belt and the Fabulous Moolah was crowned the new champion. Byers was still recognized as the champion by the American Wrestling Association (AWA) after it split from the NWA, and Penny was chosen to challenge her for the newly created AWA Women’s title. Banner won her first singles title on November 25, 1960, capturing the NWA Southern Women’s Championship (Georgia version) and then grabbed the NWA Texas Women’s Championship on March 8, 1961, defeating Nell Stewart in Fort Worth, Texas. Byers, however, no-showed the event and promoter James Barnett decided that a nine woman battle royal would be held in Angola, Indiana to determine the new titleholder. Banner was the last woman standing at the end and was named the new AWA Women’s World Champion.

She held the belt until she vacated it on January 1, 1963. She and her husband had moved to Charlotte, North Carolina in 1962 and he decided that they were going to settle down there. Thus, in the midst of the most important run in her career, she was forced to give up her title. Although she defeated Nell Stewart for the NWA Texas Women’s Championship again in 1963, the rest of her career was spent in the vicinity of North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia and Florida, thus limiting her opportunities. Nonetheless, she was still a very popular performer and was able to gain title shots against Moolah, who now reigned over women’s wrestling. The two met 15 times from 1963 through 1973 with the matches ending without a decision twelve times, with Penny winning one non-title match and with Moolah winning twice. Banner claimed that on both occasions Moolah had “cheated” to win by holding the ropes.

Banner had more to complain about with Moolah besides her in-ring tricks. She resented not only Moolah’s stranglehold on the Women’s title belt, but also on the careers of the women who trained under and wrestled for her. Penny stated that Moolah demanded exorbitant fees from the wrestlers and accused her of forcing the women to engage in salacious behavior in order to get bookings.

In a blog post she said that Moolah “sent women to promoters who demanded sex, either with the promoter or his wrestlers… It’s wrong to speak bad of the dead, but the comments in the mainstream press and even A.P. wires come dangerously close to making Moolah seem like some kind of saint, and from a pro wrestling point of view as some kind of legendary tough shooter. That’s utter bullsh*t.”

Penny, known for having a positive and bubbly personality, had other reasons to be upset. For years she had hidden the secret of her failing marriage with Weaver. She said that Weaver was unfaithful for years, sleeping with “ring rats” throughout their marriage. She also implied that he was abusive with her during the marriage, a charge that was whispered in locker rooms across the country. He even affected her wrestling career by insisting that they stay in the Carolinas and that she wrestle as a babyface after years as an established and successful run as a heel. Her predicament wasn’t unique however, as she witnessed many of her fellow female wrestlers suffer abuse at the hands of their wrestler husbands. Her best friend and former tag teammate Betty Jo Hawkins was in an abusive relationship with her husband, wrestler Brute Bernard. Banner recalled to Mooneyham an incident that occurred on the road. “Brute and I once had a big fight at the Avery Hotel in Boston. He slapped Betty Jo, and I jumped his back like a monkey. After that I would only go see Betty Jo when he wasn’t home.”

Her frustration with the various parts of the wrestling industry made her decision to retire from the sport in 1977 an easy one. In a 2004 interview with G.L.O.R.Y. Wrestling, Banner explained that: “There just were no girls to wrestle, and Moolah’s school by that time was blooming, and finally her girls were being sent off to different territories, and I simply had no one to wrestle. I was only wrestling one time a month for several months, and that was not enough. Actually, that is how you can get really hurt, only wrestling once in a while. So I made the decision to retire, and I did. They say you should retire while you are on top, and I did. Billy Wolfe had passed away in ’63, and there was no other school of wrestling, and Moolah didn’t want to book her school of girls against me, because she got no commission from me, only from her girls.”