by Stephen Von Slagle

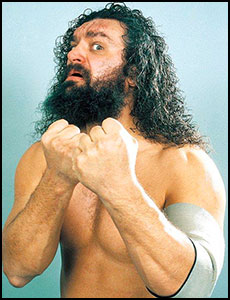

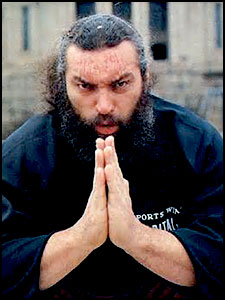

The legendary Frank “Bruiser Brody” Goodish was one of the wildest brawlers ever to step inside of a pro wrestling ring and, outside of it, he was a rebel like few others. The 6`5″ 320 lb. New Mexican madman, with long curly black hair, scraggly beard and furry boots brawled with such reckless abandon and fury that he became a true legend in every country he performed. His style and image have been emulated more times than can be counted, which is more a tribute to his unique originality than blatant copying. It can be argued that Bruiser Brody was one of the greatest, if not the greatest, brawlers the sport has ever known. But his story, unfortunately, is also one of wrestling’s most tragic.

Although billed as hailing from Albuquerque, New Mexico, Frank Goodish was born in Pennsylvania in 1946, moved to Michigan during his youth, and attended both Iowa State and, later, West Texas State, playing defensive end on their respective football teams. Following college, he had stints with both the Washington Redskins and Edmonton Eskimos and while he had more than enough athletic ability to make it as a pro football player, team sports was not the forte of the fiercely individualistic, undisciplined Goodish. Luckily, he soon found his calling in the chaotic world of professional wrestling.

He began his career in 1973 working for Leroy McGuirk and by September of the following year he won his first championship, the NWA United States Tag Team title (Tri-State version) with Stan Hansen. After finishing up with McGuirk, he travelled to Dallas and, later, the Florida territory, where he quickly became a headliner and the Florida Heavyweight champion. In 1975, with less than two years under his belt, Goodish was brought to the World Wide Wrestling Federation by Vince McMahon, Sr., given the name “Bruiser” Frank Brody, and programmed into a main-event feud with the legendary WWWF champion Bruno Sammartino. His run in the northeast was ultimately short-lived, though, as Brody became involved in a backstage altercation with Gorilla Monsoon, a member of the promotion’s management team, and was immediately let go by the Federation. It was not an isolated incident, as behind the scenes Brody was often even more unpredictable than he was inside the ring. A genuine outlaw who was never afraid to stand up for himself when he felt slighted by those in power, he was known to frequently ignore the orders of management and occasionally leave promoters in some very awkward situations. Yet despite (or, perhaps, because of) the controversy he created, the highly-talented, massive Brody was a bonafide, consistent box-office success.

He began his career in 1973 working for Leroy McGuirk and by September of the following year he won his first championship, the NWA United States Tag Team title (Tri-State version) with Stan Hansen. After finishing up with McGuirk, he travelled to Dallas and, later, the Florida territory, where he quickly became a headliner and the Florida Heavyweight champion. In 1975, with less than two years under his belt, Goodish was brought to the World Wide Wrestling Federation by Vince McMahon, Sr., given the name “Bruiser” Frank Brody, and programmed into a main-event feud with the legendary WWWF champion Bruno Sammartino. His run in the northeast was ultimately short-lived, though, as Brody became involved in a backstage altercation with Gorilla Monsoon, a member of the promotion’s management team, and was immediately let go by the Federation. It was not an isolated incident, as behind the scenes Brody was often even more unpredictable than he was inside the ring. A genuine outlaw who was never afraid to stand up for himself when he felt slighted by those in power, he was known to frequently ignore the orders of management and occasionally leave promoters in some very awkward situations. Yet despite (or, perhaps, because of) the controversy he created, the highly-talented, massive Brody was a bonafide, consistent box-office success.

His championship accolades include the NWA Western States title in 1975, four Mid South North American championships, three Texas Tag Team titles between 1977-1979, the Texas Heavyweight title, the Texas Brass Knuckles title, four American Tag Team championships (three w/Kerry Von Erich and one w/Ernie Ladd), the Central States Tag Team title (w/Ladd) and the Central States Heavyweight title in 1980. He also captured three NWA International Heavyweight championships between 1981-1988, the Australian World Brass Knuckles title, the World Wrestling Association World Heavyweight title, the PWF Tag Team championship (w/Hansen), the WCCW TV title in 1986 and the NWF International Heavyweight title in 1987.

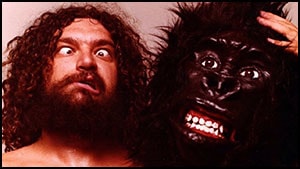

During his fifteen years in the sport, Brody wrestled both as a hated villain and a tough-as-nails babyface without ever changing his in-ring style. At the same time, he feuded with the very best in the sport, most notable are his heated rivalries with Antonio Inoki, the Von Erich family, the Funk brothers, NWA World champions Flair, Race & Rhodes and, of course, his bloody wars with Abdullah the Butcher, which took place throughout the U.S., Japan and Puerto Rico. One of his more memorable feuds was against the mammoth Andre the Giant. At 6’5″ (he was often billed as standing 6’8″) and 320 lbs., Brody was a legitimate physical challenge for Andre and he gave the Giant some of the toughest matches of his career throughout regions across the wrestling map during their multi-year feud. Another major program for Brody was his lengthy series against the legendary Dick The Bruiser, which took place in several midwestern promotions including St. Louis, Central States, the AWA and the WWA Their ongoing feud eventually led to “blow-off” matches in major cities within these various promotions, with the two brawlers fighting over the right to use the name “Bruiser.” Brody lost, and was known as “King Kong” Brody, at least throughout the Midwest, for the rest of his career.

During his fifteen years in the sport, Brody wrestled both as a hated villain and a tough-as-nails babyface without ever changing his in-ring style. At the same time, he feuded with the very best in the sport, most notable are his heated rivalries with Antonio Inoki, the Von Erich family, the Funk brothers, NWA World champions Flair, Race & Rhodes and, of course, his bloody wars with Abdullah the Butcher, which took place throughout the U.S., Japan and Puerto Rico. One of his more memorable feuds was against the mammoth Andre the Giant. At 6’5″ (he was often billed as standing 6’8″) and 320 lbs., Brody was a legitimate physical challenge for Andre and he gave the Giant some of the toughest matches of his career throughout regions across the wrestling map during their multi-year feud. Another major program for Brody was his lengthy series against the legendary Dick The Bruiser, which took place in several midwestern promotions including St. Louis, Central States, the AWA and the WWA Their ongoing feud eventually led to “blow-off” matches in major cities within these various promotions, with the two brawlers fighting over the right to use the name “Bruiser.” Brody lost, and was known as “King Kong” Brody, at least throughout the Midwest, for the rest of his career.

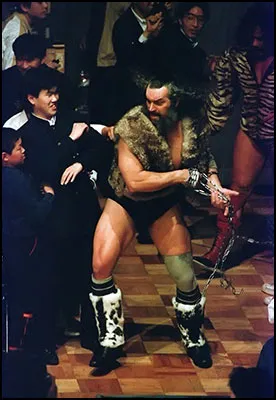

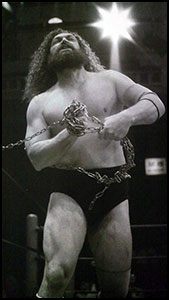

After making his Japanese debut in a tag match with Curtis Iukea vs. Giant Baba and The Masked Destroyer in January of 1979, Brody quickly created a second home for himself in the Land of the Rising Sun. Wrestling with a fury and unpredictability that Japanese fans had never witnessed before, Brody became a legitimate superstar there, a mainstream Japanese celebrity and one of the highest paid wrestlers in the world. The chaos that the gigantic American brawler created just getting to the ring, wildly, dangerously, swinging his heavy steel chain overheard as the audience frantically scrambled in fear and delight, was truly the stuff of legend. Inside the ring, he exhibited the same reckless abandon, often alongside his equally unpredictable partner Stan Hansen. After more than five years competing in Shohei Baba’s All Japan promotion, Brody eventually made a very controversial, unexpected, high-dollar jump to Inoki’s New Japan group and his fame and success followed.

After making his Japanese debut in a tag match with Curtis Iukea vs. Giant Baba and The Masked Destroyer in January of 1979, Brody quickly created a second home for himself in the Land of the Rising Sun. Wrestling with a fury and unpredictability that Japanese fans had never witnessed before, Brody became a legitimate superstar there, a mainstream Japanese celebrity and one of the highest paid wrestlers in the world. The chaos that the gigantic American brawler created just getting to the ring, wildly, dangerously, swinging his heavy steel chain overheard as the audience frantically scrambled in fear and delight, was truly the stuff of legend. Inside the ring, he exhibited the same reckless abandon, often alongside his equally unpredictable partner Stan Hansen. After more than five years competing in Shohei Baba’s All Japan promotion, Brody eventually made a very controversial, unexpected, high-dollar jump to Inoki’s New Japan group and his fame and success followed.

As was the case everywhere he wrestled, Bruiser Brody was one of the biggest stars and box-office draws in the Puerto Rican-based World Wrestling Council, where he had legendary matches with Abdullah and Carlos Colon. But his feud with the Masked Invader (Jose Gonzalez, co-owner of the WWC) proved to be the last of his career. The events that took place in Puerto Rico the summer of 1988 have been well-documented in books, documentaries and television programs. On July 17, 1988, Frank Goodish a.k.a. Bruiser Brody was murdered in a Puerto Rican locker room, the victim of several stab wounds to the abdominal area. He was 42 years old.

As was the case everywhere he wrestled, Bruiser Brody was one of the biggest stars and box-office draws in the Puerto Rican-based World Wrestling Council, where he had legendary matches with Abdullah and Carlos Colon. But his feud with the Masked Invader (Jose Gonzalez, co-owner of the WWC) proved to be the last of his career. The events that took place in Puerto Rico the summer of 1988 have been well-documented in books, documentaries and television programs. On July 17, 1988, Frank Goodish a.k.a. Bruiser Brody was murdered in a Puerto Rican locker room, the victim of several stab wounds to the abdominal area. He was 42 years old.

Jose Gonzalez was charged with the murder, to which there were several eyewitnesses. Tony Atlas, in a statement to police at the time, told the authorities that Gonzalez had approached Brody, asked to speak with him in the shower area, and that Gonzales had then stabbed Goodish in the torso several times. Atlas also stated that Gonzalez attempted to slit Brody’s throat.

Gonzales, stating that he was acting in self-defense, plead not guilty. Unlike in the United States, the jury in a Puerto Rican murder case does not have to come to a unanimous decision, and whichever way the majority of the jury votes is how the verdict is rendered. Although Puerto Rican law came to a different conclusion, most familiar with the case believe Brody’s murderer walked away a free man.

The news of Brody’s murder sent shockwaves through the world of wrestling and the World Wrestling Council, once a true promotional hotbed, all but disappeared after the fallout from negative publicity, not to mention the devastating loss of American talent who refused to work in Puerto Rico after Brody’s murder. But the loss of the WWC as a major territory pales in comparison to the loss the sport, and more so, his family, suffered when Frank Goodish died. Professional wrestling lost a true legend on that steamy July night, the likes of which we may never see again.

The news of Brody’s murder sent shockwaves through the world of wrestling and the World Wrestling Council, once a true promotional hotbed, all but disappeared after the fallout from negative publicity, not to mention the devastating loss of American talent who refused to work in Puerto Rico after Brody’s murder. But the loss of the WWC as a major territory pales in comparison to the loss the sport, and more so, his family, suffered when Frank Goodish died. Professional wrestling lost a true legend on that steamy July night, the likes of which we may never see again.

“King Kong” Bruiser Brody was voted “Best Brawler” by the readers of the Wrestling Observer Newsletter an unprecedented seven times between 1980-1988. Following his death, the “Best Brawler” award was renamed the Bruiser Brody Memorial Award. Additionally, the renowned Japanese daily sports newspaper, Tokyo Sports, honored Brody with its Lifetime Achievement Award (1988) and he was chosen to receive the prestigious Frank Gotch Award by the George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame (2018). Brody is also a member of the Wrestling Observer Hall of Fame (1996), the St. Louis Wrestling Hall of Fame (2007), the Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame (2014), and the W.W.E. Hall of Fame (2019).